Blu-ray Review: Criterion Unearths FESTIVAL, or, 1967: The Year Folk Broke

1967 was an indisputably pivotal year for the documentary genre. Not just because it was the year that seems to have birthed the “rockumentary” subgenre - or music doc - but because the impact of that catalytic epiphany to explore performance also prompted a total re-invention in the documentary filmmaking approach. I’ve already spent a great deal of the year exploring the ingenious new wave practitioners of direct-cinema, considering 50 years ago, two of the most seminal examples of not only the music documentary, but the documentary genre at large, were both shot and released.

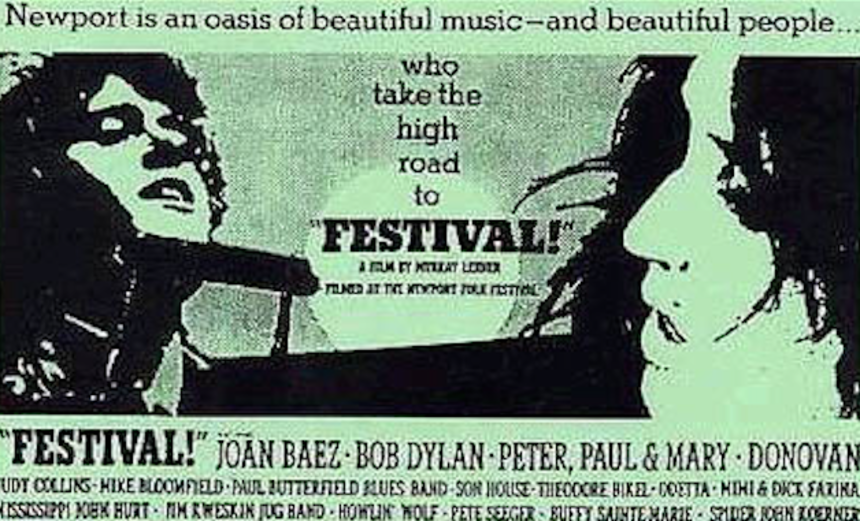

The Criterion Collection has already honored both D.A. Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back, which was shot in 1965 and released in ‘67, and Monterey Pop, which was shot in ‘67 and released the following year, with glorious packages. Earlier this year, I was fortunate enough to have had the chance to speak with Mr. Pennebaker - or Penny - about both of these incredible relics and our discussion offers some great background info for anyone coming at the film of today’s discussion without context. For, in addition to Pennebaker’s incredible achievements - successes on more levels than one can fathom: technically, historically, etc... - there is a third, lesser known but equally important, film that also surfaced in 1967. Thanks to the Criterion Collection, after 50 years of obscurity, Murray Lerner’s Festival can be appreciated in all its highly-dense glory.

Could 1967 really be the first occurrence of the music documentary, as I’ve somewhat recklessly suggested in the past? Well, yes and no. Yes, in the sense that it was something of a big-bang year for films of its specific kind, but no because, well, no. I can point to a film from 1959 which is a clear precursor to Murray Lerner’s Festival - the delightful Jazz On A Summer’s Day, which presents us with a breezy moment in time at The Newport Jazz Festival. That film is the kind of far gone postcard you wish could come to life, and through the magic of documentary, it can and will forevermore.

Murray Lerner’s Festival documents not one fargone day, but four years, from 1963-66, of The Newport Folk Festival, which was an offshoot of the jazz festival, as the folk renaissance picked up steam in popular culture. Folk was, after all, a great cousin to jazz, as was blues, as was grass country, and within the same year of Festival’s release, the Monterey Pop Festival exploded like a trilogy-ending happening to end all happenings - one that fused all musical cousins and intellectual brothers and sisters in profound union. Monterey was the zenith of the festival experience as introduced by Newport Jazz, carried on by Newport Folk, and eventually tarnished forever by the violent energies of Altamont; the night peace lost.

But still, could 1959 really be the first occurrence of the music documentary? In looking at a random list online of pivotal documentaries of the last century, supplied by The University of Berkeley, it would appear so. If this is true, I wonder if the reason for this stems from the fact that the documentary was reserved for more serious matters of more flagrantly historical import. Performance, on the other hand, seemed relegated to fiction, if not the epitome of fiction. What is show business, if not the business of putting on a show, and what is the musical, if not the ultimate song and dance variety show? What are the great vaudevillian celebs turned film stars, The Marx Brothers, without their trademark non sequiturs into music - when Chico’s piano playing and Harpo’s harp musicianship were at once dazzling and hilarious?

So, if film, as entertainment, follows from the great vaudevillian tradition, is this why music seemed destined for over half a century to support a narrative, rather than drive it? Even when rock & roll finally crashed through the celluloid gates, in order to see Elvis singing and gyrating, while the musical numbers were the traditional meat and potatoes of the musical, the audience still had to endure plot; even if that plot went as far as to concern “kissin’ cousins”. Richard Lester’s, A Hard Day’s Night, was certainly a music-film revolution, but it is no documentary and like the most generic films of its ilk, in a film ostensibly about The Beatles, as if that subject wasn’t interesting in and of itself, the film is still concerned with whimsical plot points like the whereabouts of Paul’s wayward grandfather.

As a comedy, A Hard Day’s Night is a delight. As a satisfying representation of music, it highlights what is potentially the chief issue with “music films” before 1967, forgetting for a moment Jazz On A Summer’s Day - the proto-Festival. The issue, or a fundamental issue, involves sync sound. If film offered vaudevillian live performers anything, it was the opportunity for perfectionism; the ability to prepare and convey a performer’s routine enabling the final product to epitomize the act. The triumph of the direct-cinematographers was their innovation in shattering that perfectionism, championing instead the truth and all it entailed. For a performer, the truth might entail failing to hit a note at a concert, or taking a misstep within a choreographed dance routine. For a public person who depends on his or her perception, the truth could entail behaviour that is less than likable. For a filmmaker, it means shots that aren’t always gracefully composed - sudden movements, iffy focus, etc - but it also inadvertently created the fundamental notion of the beautiful accident; the idea that another form of movie magic exists between the lines of supposed subject - a cinema of subtext.

If musicians were considered beneath the documentary genre as a central subject it took cheapening the production value to illustrate the subject’s true worth. What direct cinematographers effectively did in picking up the camera off of the tripod, was to disrespect the immaculate pedestal of apparatus in favor of capturing real moments. I doubt it's any coincidence that some of the first subjects to undergo this new direct documentary treatment were subjects like Bob Dylan, who seemed to live to cut through bullshit, and The Newport Folk Festival, where truth took on its own youth-movement, until even it was taken off of its high horse by the great shit-cutter himself, Bob Dylan.

Rather than preparing reality with great care - in some cases even staging reality, as was somewhat the custom - new documentary filmmakers like D.A. Pennebaker flew by the seats of their pants, following subjects like Bob Dylan into closed rooms and into limos for street-level portrait looks at their subjects, and after these cornerstone films, there really was no looking back. This thirst for spontaneity and aversion to convention, that so mirrored the stimulating rising tides of the streets, was an attitude that was certainly brought into the editing room when assembling the mood of these films, taking documentary auteurism to brave new worlds. It’s worth stating here that Howard Alk, a guest-cinematographer and assistant director on Dont Look Back, was Festival's lead editor.

This desire to re-invent the wheel, or perhaps redefine it, is why Murray Lerner or Howard Alk chose to begin Festival, not with a performance, not with a shot of the festival grounds, but with an interview in some unidentified year, by an unnamed band. Criterion's optional on-screen title cards will clarify that the jug band in question is Jim Kweskin & The Jug Band, featuring a young Mel Lyman, who does most of the speaking in this opening scene. Forget the fact that Lyman, the harp-blower, will soon go on to form the Fort Hill Community (or cult?). For the purposes of this film that initially didn't bother to indetiy its artists with text, all the audience sees is a bande à freaks, presumably in the latter years of the shoot, as the intellectual youth began waving their freak flags increasingly high. The scene begins with a performance that, after a minute, is pre-emptively interrupted by a ‘cut’ from behind the camera. Moments later, once the camera is turned back on, we see the band laughing and indignantly questioning the audacity of the choice to cut them short.

Jim Kweskin: Excuse me. Did you just cut in the middle of that song?!?

A cameraman - maybe Murray Lerner?: Yeah.

JK: You guys better get together.

Mel Lyman: If we'd really been blowing he couldn't help but listen.

JK: He's interested in making a film.

ML: He’s running the machine.

JK: He's making a film of what he wants to see in the film.

ML: He’s blowing with us anyhow - we are all playing machines, you know, (looking into camera) If you really blow on your machine there, then you're playing music too, don't you see? if you really swing with that machine there.

A bandmate chimes in: I can't tell you what kind of guy I am. You might say, ‘he's a freak’... and you might be right... but when I pick up a jug and start playing it, you know I'm a freak, right?

ML: See we’re trying to take our understanding - our perception of truth and put it in a form so that you can hear it sensually, with your ears. Like a painter takes what he knows of the truth and puts it on a canvas so the people can dig it in a sensual way with their eyes. Music happens to be an ear thing, that's all.

On what grounds do you go about evaluating a historical documentary, especially one as dense and entertaining as Festival, a container of so many ideas and varying ideologies melding, when social progress was still in its infancy, but the groundwork was exhilaratingly sound. Surely, it must come down to 1) a film’s technical and aesthetic achievements and 2) the film’s historical value. Technically, the film is so artfully assembled, that even after 50 years of redundant entries into the subgenre, Festival still stands out as an original and visionary conception. From the brilliant aforementioned introduction, to the breathtaking opening credit sequence that tracks the arrival of the festival goers in a single long shot that words fail to describe, all to the tune of, “come and go with me to that land (where I’m bound)” as sung by Peter, Paul and Mary. This not only announces a glorious welcome to the world of this film/event, but in retrospect, it also feels like a figurative arrival of a movement that is indeed bound for glory.

Throughout the film, we see the delivery of the opening scene’s promise realized scene after scene. We see Lerner and Howard Alk, ‘blowing their machines’ along with every performer present. Woody Guthrie, whose own machine “kill(ed) fascists” had recently passed away as a baby-faced Dylan wept at his deathbed - at least as far as my most romanticized imaginings are concerned - and now an inspired new generation of thinkers was joining forces with the peers of Guthrie to play their machines alongside the heritage voices of Son House and Howling Wolf. That Lerner and Co’s machines fused so effortlessly, year after year, through priceless interview after interview, is one of the great feats in documentary filmmaking. This is why Festival stands proudly alongside Dont Look Back and Monterey Pop, not just because of its time and place fortuitousness, but because of its innovation in methods of storytelling. Dylan learned from Guthrie how to convey stories of truth and he took that wisdom to blessed, almost “shamanistic” levels, as Allen Ginsberg said of hearing Hard Rain for the first time.

‘Hard Rain’ was indeed about to figuratively downpour on the folk revolution and it would be Dylan himself who’d deliver the storm. It would be easy to spend this entire review discussing the events of Newport ‘65, which fell like a brick shit house shortly following the time immortalized by Dont Look Back. Likewise, it would be very easy for Lerner’s entire film to culminate or revolve around the night that many rock critics refer to as among the most shocking in rock and roll history. Hell, Elijah Wald, who helped Dave Von Ronk pen his autobiography, "The Mayor of MacDougal Street", which serves as the source inspiration for Inside Llewyn Davis, wrote an entire book about it! Lerner, however, somehow manages to steer clear of allowing Dylan to steal the show, while still positioning the event and its priceless, dare I say, Zapruder-like, footage (comedy is tragedy + time) with a sense of understated prominence.

That Lerner is able to accomplish this is one of the many reasons that, even for the modern seasoned documentary zealot who’s seen every approach under the sun, Festival remains entirely original in its smorgasbord presentation of The Newport Folk Festival. The obvious editing choice might seem to be to present the four years' worth of footage chronologically, but Lerner blurs time and scatters it like a tapestry that condenses an entire movement – The Folk Renaissance; not as a moment-in-time, but its entire moment throughout the duration of its time, collaged to paint a picture - a vision of reality. Yes, the kids had been gathering to play folk at Washington Square Park every Sunday for upwards of a decade before the very first Newport Folk Festival, but these pivotal years when intellect-driven music crashed through the doors of popular culture, re-directing pop music away from Patti Page's "How Much Is That Doggy in The Window?", and forcing ideas as the domineering currency to the centre of attention was best epitomized by The Newport Folk Festival, and that is apparent in every bit of endless truth Festival captures, and just as, if not more importantly, conveys.

This brings us to the second mode of evaluating the documentary or ‘truth’ film, and that is its historical value, aka, what is being captured (not how). Historically speaking, as I’ve already mentioned, the biggest elephant in the screening room is Dylan, even though the film absolutely transcends that incident in its rounded portrayal of the heart of folk from 1963-66. Even when Dylan isn’t on the screen, he is still often present. For example, Festival re-introduces us to Joan Baez as the adorable ball of wisdom she was, even as a child of 18 years old, playing with seasoned folk players as equals. The insight in her interviews and the kind ways she bemusedly engages her fan base can’t help but seem warm in the face of what we know about Dylan’s reluctant stardom. It’s never hard to forget that Dylan was rightly heralded as the face of the folk’s proud truth and authenticity movement and few people loved the ‘raggamuffin’ deeper than Joan at that moment in time.

One of the film’s unintended ironies, one thinks, occurs during a Peter, Paul, and Mary performance, who were heavyweights, known to steal the Newport show - even if Festival’s features teach us that Yarrow, who planned the event, was always sure to give his band prime billing. Dylan, who’s hobo voice was never appreciated quite as much as his prophetic words, is to this day among the most covered artists of all times - comparably as much as the traditional songs that he and his folk generation perpetuated into immortality. So even when Dylan - the man - is nowhere in sight, his songs filled the air through the years. In 1963, I think, we see it when Peter, Paul and Mary passionately bellowed Blowin’ In The Wind, or more on point, in 1964, when they chanted The Times They Are A Changin’

Because Lerner sort of splashes the footage together without chronology, one can't be precise on what year we’re watching, but I’m guessing it’s in 1964, when a batch of Newport attendees, maybe in their early 20s, are interviewed the day after a Dylan performance, offering another example of Dylan’s offscreen presence.

Fest Boy 1: People start to idolize these artists, you know, and once that happens– like Dylan yesterday, masses come over and they all just sit there like (feigns awe) “It's Bob Dylan! it's really him!” Everybody around here wants to be a bum and to be famous for it... I do like Dylan's music and I don't really need to see him – though he's a really good performer.

Fest Boy 2: When he gets to be, you know - ‘there he is - there's a man – God!’, who needs him anymore? He's accepted and he's a part of your establishment and forget him.

What these distant Dylan fans didn’t realize, as nobody at the time could have really, is that Dylan basically agreed with them and was working towards his own monumental backlash against the thing that worked so hard to own him - a community of entitled disciples that supposedly admired him for his truth, but could not handle the idea of his truth differing from their cause. In the minds of many people who saw the music and the message as one, folk was supposed to be about social justice. It’s not that Dylan rejected social justice music - far from it - he penned some of the finest justice ballads ever conceived - it’s that his definition of folk extended far beyond the limits of ‘the cause’. Folk is many things - so many that you could argue that the term has been rendered meaningless - but I think the fundamental aspect that was certainly of great appeal to Dylan, was that folk, like rhythm, like blues, was and is, first person music. It’s any person music, it’s every person music.

It’s giving a voice to the voiceless and in that it is indeed a community of perspective inclusion. That is what Newport stood for at its best, so why on earth would Dylan spit on that with the arch nemesis of the acoustic guitar - the official machine of the folk movement. Dylan went electric in the great folk tradition to which he so excelled. He reappropriated Down On Penny’s Farm (yet again!), this time to the tune of, “Well, I try my best to be just like I am, but everybody wants you, to be just like them, they sing while you slave and I just get bored.” In Lerner’s Festival, we see Dylan's truth in 1963, we see it in 1964, and in 1965, we see an artist busy being born, continuing to honor that first person authenticity, whether it meshes with the beloved festival’s overarching narrative or not. It’s this very resistance to inauthenticity at all costs that unites Dylan with roots folk and the beats before him, as well as the punks and post-punks after him. This is the continuum of the resistance; the declaration of independence and the refusal to be a living advertisement for anything.

Dylan bids the dropped faces of his adulators an ‘it’s all over now, baby blue’, and Lerner’s film is only 2/3s finished. But an electricity has permeated the proceedings. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, with its shared members of Dylan’s electric onslaught, also offered an electric presence, as did Howling Wolf. As Peter, Paul and Mary knowingly herald, “The times they are a changin’” and by 1966, indeed they were. In this regard, Festival is also a look at the pre-emptive years foreshadowing the freak revolution, when the growing fad of free-thinking intellectualism joined Dylan in plugging into electric wavelengths. The story goes that Lerner had to be talked into calling his film ‘finished’ once and for all after ‘66 and was able to release it just in time for the end of 1967, to live alongside the rock-doc greats of its year. By this point, times had already changed so rapidly, that the film barely made it in time to be relevant. As a cinematic experience today, as well as a time capsule, Festival is exhilarating.

In continuing to evaluate Festival in regards to its merit as a historical document, watching the film 50 years after its release, next to electric Dylan, the second biggest elephant in the screening room, if you'll forgive my continual usage of the phrase (tm), is the ‘the times, they have a-sure changed’ element... And not for better, as far as musical happenings are concerned. Wikipedia defines a ‘happening’ as, “a performance, event, or situation meant to be considered art, usually as performance art.” Webster adds, “an event or series of events designed to evoke a spontaneous reaction to sensory, emotional, or spiritual stimuli.” Does the music “festival”, as defined by Lerner’s film even exist anymore? To quote the opening paragraph of Amanda Petrusich‘s essay, ‘Festival: Who Knows What’s Gonna Happen Tomorrow?’ (which can be found in the new package’s booklet):

From a certain age and vantage point, the experience of the summer music festival in its present form—with its complex configurations of portable toilets, its vast and hierarchical lineups, its lurid bacchanalian atmosphere—may appear more harrowing than fun. To invoke any ideology beyond remorseless capitalism and self-promotion for such an event would seem naive now, almost two decades into the twenty-first century, when the idea of the festival as a significant cultural or political happening is a thing of the past. But Murray Lerner’s 1967 documentary Festival, shot at the Newport Folk Festival from 1963 to 1966, reminds us of the original model: a gathering of like-minded people who were drawn not only to the populist music they were playing and listening to but also to genuine engagement in the larger questions that were agitating their society.

Watching the opening credits of Festival, wherein fresh, thinking faces pilgrimage into the small town to partake in a real communal event - and then also watching this sequence echoed in the opening credits of films like Monterey Pop or Woodstock - you get a sense of the spontaneous aspect of the happening; a sense of purpose and the beauty of partaking in an event that felt bigger than any of its one attendants. Today with the eye-abusing pollution of advertising and general distractions that cacophonously combine to bury the performance emphasis, it’s hard to see past the bottom line of what’s become of the festival intention, as defined by Newport. It doesn’t say much for the present, but imagine for a second what would happen if it were possible to pluck one or two of the fresh young fellows from Festival and place them in the center of Coachella. Spontaneous combustion? To be reminded of and remain inspired by more exciting times is the very essence of a good documentary’s worth. Festival is now one of the finest in my collection.

I will not be going into great detail regarding the Criterion collection’s supplemental features, as I usually do in these reviews. I will tell you that they alone are worth the purchase, but I would also tell you that the film itself, especially with its wonderful newly restored 2K digital transfer and hair-raising sound, is well worth the purchase - for a certain type of collector, like myself, it is essential. I can tell you that there are several additional full-song performances by the likes of Johnny Cash, Odetta, Son House, and more, and I can implore you to enjoy the two five-star featurettes, one pertaining to the filmmaking and the other from the perspective of the performers. I can also assure you that the essay by Amanda Petrusich in the package’s booklet is well worth the read. But if you’ve made it this far down in this review, I doubt you need much coaxing. This film and its Criterion package sells itself. It is worthy of your top shelf. However, if you must hear something in the way of a spoiler, I’ll leave you with a priceless retrospective quote from an old Pete Seeger:

Somebody - usually a white person - has made up a song and copyrights it and now stands behind a microphone singing it and sells a recording of it - that’s a folk song. Some old grandmother in her rocking chair, singing a 400 year old tune to her baby - she’s not a folk singer, she’s just an old woman singing an old song… so I use the term as little as possible.