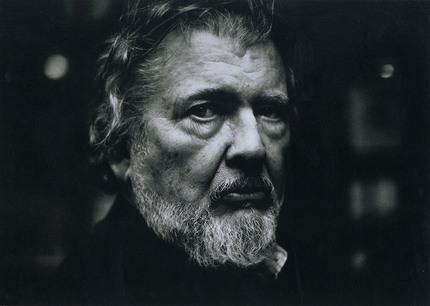

Interview: Director Walter Hill on THE ASSIGNMENT, Star Quality, and the Late Bill Paxton

With a career that started early as Steve McQueen’s screenwriter, Walter Hill has more than made his mark on American cinema. The writer of The Getaway and Alien, and director of Hard Times, The Warriors, 48 Hours, Streets of Fire, Wild Bill, and so many iconic films spoke with me about his latest, the neo-noir crime thriller, The Assignment.

The Lady Miz Diva: THE ASSIGNMENT came under controversy practically from the moment it was announced. Do you think there were misconceived notions about the film? What was your take on the controversy?

Walter Hill: Well, I certainly think that there are some misconceptions. Where to begin? The movie was attacked because the premise was felt to be in some ways disrespectful to the transgender movement, or exploiting the transgender movement, and was attacked really before we were beginning to shoot. So, I obviously disagree with that on so many different fundamental levels.

But I have to also say within the framework of this, I think to attack things that you have not seen is a fairly weak intellectual position to start with, and makes dialogue and discourse rather difficult. And by nature, as well as circumstances, I chose not to get into any kind of polemical situation; I was asked to make statements and I declined. I thought, as I said, the film will be my defense, and as far as I’m concerned, the film is my defense, although I am speaking about this. So, let that be the preamble about this.

Number one, it is not a movie about the transgender experience. We live in the gender fluid age and society now, compared to the world that I grew up in, the country are grew up in. I think that’s a good thing. I have no particular attitudes about it. Times change; it’s a very different world and I’m glad that people are getting to express themselves and their way and their choices that they’ve been harboring within.

I think it’s a good thing that they are now able to come and face the world directly, hopefully without problems and prejudice. I’d like to say this goes without saying, but I guess you have to say it; the idea that I would purposely set out to make people’s lives more difficult that are on this journey, is rather dispiriting. People come to watch movies to be entertained. I certainly don’t want to make anybody’s life - their journey through this voyage that we’re all on – more difficult.

I do not think the movie has anything really to do with the transgender experience. There is a very big difference between transgender and genital alteration. Frank Kitchen goes through genital alteration. Frank Kitchen is a guy. Frank Kitchen starts out as a guy. Frank Kitchen is a criminal. He is double-crossed, he is knocked unconscious, he wakes up, he seems to have the body of a woman, but he is still a guy. He’s a guy inside his head and he is a guy every scene in the movie.

This would seem to be perfectly consistent with transgender theory; that is to say we are who we are inside our head. But Frank’s experience is the opposite of the transgender experience, which one is, if you opt into the surgery: Frank is a guy who, against his will, is genitally altered, and he’s still a guy. Transgenders, if they opt for the surgery, are guys who become fully guys, or women inside their heads then become women, physically. So, I just don’t see the critique about that.

It’s a movie about revenge. It’s double tracking. We have a brilliant surgical doctor, who is also an intellectual, who is hell-bent on revenge for a very reasonable reason; Frank very cruelly murdered someone that she loves, a member of her family. Frank is, as opposed to this bullying intellectual figure, he is the desperate product of the streets. A Darwinian survivor of the criminal underclass.

He has a brutal, amoral sensibility at the beginning of the movie. And both characters through the up-and-down of the drama, end up – how do we say this – I thought I had a double task, the two characters end up sadder but wiser about themselves, shall we say. And the audience, hopefully, if I’ve done this right, has a degree of sympathy for both characters.

You should not approve of the characters; they do not become saints and they do not become wonderful people, but they are recognisably human in a better way than when we first began the journey. And she is going to tend to her own garden now, and live with her own ideas in a very restricted way; he is going to take the tools that he has, and it’s rather vague {in the film}, but he’s going to try to be a vigilante for causes that he thinks are proper. He’s no longer going to be in the murder for hire business.

So, to me, that’s what it’s about. I don’t see that there’s much to do with what originally made some people angry. We live in times that are, as I said, gender fluid, but there are also heightened identity politics. I don’t like identity politics. I think it’s a wiser thing that we discover we’re all in the same boat in our humanity, and we proceed trying to have a large tent that we can all function within, rather than magnifying the differences between us.

LMD: I had a bit of hesitation watching this and wondering if the worst thing that the doctor could do to Frank was turn him into a woman?

WH: No, she addresses this in the deposition. In the scene, she double tracks on the explanation. She has given him a new opportunity in life. She radically altered his conscious self in an attempt to give him a chance at a new life and improvement. She says, “The most noble of all things is a woman; the most developed of all.” He fails this test. He is not better, as far as she is concerned. He remains exactly who he was inside his head. He, as she puts it, “takes up the gun.” He goes right back to the gun.

What she then points out is an exact reproduction of most cis-gender theory, which is, we are what we are inside our head, and that’s it. One part of the experiment was a failure and the other was a success. She is on a revenge trail at the beginning, but the deeper she thought about it, revenge was just the surface, and then the scientific took over; her need to experiment. She is an intellectual, and she is a woman of great ideas and great intellect.

LMD: She’s very Frankenstein.

WH: Well, there’s only a few stories and most of us only know a few. The great Borges always said there’s only two stories; The Crucifixion and The Odyssey, and all stories finally came back there, which I guess if you make your categories broad enough, you can make anything fit.

LMD: I did find it somewhat ironic that this whole brouhaha was based around the man who was responsible for turning the character of Ripley in ALIEN into a woman. Ripley, of course, is one of the most beloved characters in cinema, as well as being the template for the “badass female” in film.

WH: Well, Ripley is taken from Ripley’s Believe It Or Not; that was the overall story idea. But her name was Ellen Ripley, and Ellen is my mother’s middle name. {Laughs.} Usually people that are writers, directors all that tell you that they have these terrible childhoods, that they didn’t get along with their parents, or something like that; I got along with my parents very well. I miss them still both, very much, and I was very close with both my mother and my father. Our second daughter is Miranda Ellen, and I’ve kept the name going the best I can many times. I’m sorry, I’ve cut you off.

LMD: No, not at all. I wanted to discuss the fact that originally Ripley was a male character, and also the Miranda character from STREETS OF FIRE was originally written as male. What is it that goes into your thinking when you transform the character that way? Is it the character or the performer attached to the role that changes things?

WH: I think a little of both. Howard Hawks used to always say, any time you can turn them around, any time you can pull a reversal, it’ll always add to your drama. Rather than just have men chasing women, it’s more interesting if the woman chases the guy. Famously, in the MacArthur/Hecht play that he uses as the newspaper drama with Cary Grant…

LMD: HIS GIRL FRIDAY, which was originally THE FRONT PAGE.

WH: Very good, Diva. My memory for titles is always weak. The Rosalind Russell character was a guy. So, I think I was open to the notion, because Hawks was certainly one of my favorite filmmakers. And the combination of opportunity… I think in the case of Sigourney’s character in this movie, the more I thought about it, the conception of the doctor’s personality as a guy seemed a very familiar idea; When you made him really smart and very intellectual, it inevitably crept into the mad scientist kind of thing. I thought with a woman, it wouldn’t get… I mean, she is not a healthy person, however, I don’t think she falls into the category of mad scientist.

LMD: Please tell us about Michelle Rodriguez, who really has a difficult path in this film.

WH: She does it so well. It’s a wonderful performance, and it’s a very brave performance. And I think she’s absolutely credible in the movie. She told me when we first met, *affects gravelly voice*“I don’t know who you’re going to cast in this, but you’ll never find anybody that’s as good with the guns as me.”

LMD: Just like that?

WH: Absolutely. If anything, tougher, and she was right, she was absolutely right. At the same time, as I say, she does a wonderful job, but underneath, she’s a very sensitive person. I liked her very much, I loved working with her very much.

LMD: I felt like THE ASSIGNMENT was very much representative of your signature style. I was reminded of your 80s’ films like 48 HOURS and STREETS OF FIRE. The colour schemes have that trademark grainy, murky look punctuated with bright jewel tones, and the music themes are composed by the great Giorgio Moroder (Though I was expecting Ry Cooder). And the action in the film is relatively low tech with gunfights compared to many current action films. Was this a look back for you?

WH: I don’t know, you make a lot of decisions that are just kind of instinctive; ‘Let me try this,’ ‘let me do that,’ ‘let’s do this.’ I think that whenever you make a movie that’s by intention noir-ish, or neo-noir-ish, you are in a sense, making something retro. That’s just inevitably part of what you’re up to here.

And the kind of shorthand, comic, graphic novel style is another bit that probably is a bit on the retro side, because it doesn’t emphasize certain kinds of psychological reality. Although, you don’t ask actors to play comic book characters; you tell them to be as real as they can. I’ll supply the world that they’re operating in, but you guys play human beings; play them as best you can play them, and with as much nuance and subtlety as we can muster here. I guess I’m just rambling along, but I’m struggling with your question…

LMD: I’m sorry.

WH: No, it’s a good question. And I said yesterday I thought this movie was very much an extension of my work on the Tales From the Crypt. Denis Hamill wrote the original story and screenplay back in the late 1970s, and I read it then and it was very lurid and very interesting and God knows it was different. It was audacious and I always like that kind of thing; not that that kind of thing was very common in this instance {Laughs}. I just didn’t know how to do it. I couldn’t get it right in my head. I optioned the material a couple of times, I allowed the options to expire. I wrote the script, which I abandoned because I could see later it was too real; I was trying to put it too much in the real world.

And then after my Tales From the Crypt experience - I did three of them - I really felt that I had suddenly had this revelation – that’s how to do it, do it like it’s Tales From the Crypt. That immediately connects it in some ways, certainly not in every way, but in some ways, to films I’ve done like Streets of Fire, Johnny Handsome. So, I guess once again, I plead guilty.

LMD: Regarding 48 HOURS, you said: “I never claim it's the best movie or anything like that, but it did turn out to be a very imitated film.” How do you feel when you see some of your innovations imitated, or some of your films even being considered for reboot {THE WARRIORS}?

WH: Well, I’ve seen two or three versions of Hard Times, already. How do I feel about it, I think there’s two ways you can go: You can take the Oscar Wilde position that “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery…” and let it go at that, or you can say, ‘Jesus, I’ve been robbed!”

Maybe this is left over from the 60s, but I just think it’s better to think positive and move on. If someone wants to borrow something, fine. I hope they use it well and I hope it brings them the effect they want. I wouldn’t say that I have never borrowed an idea, or a shot, or something; all directors kind of borrow a bit, I’ve always said.

When I first started working, people said that I was very much in the school of, or that you could see direct connections to Sam Peckinpah. That’s what other people said, they don’t say it much anymore. But what I’m trying to say – and take me out of all this, this chain – Peckinpah was very much beholden and indebted to the films of Kurosawa, and Kurosawa was very much influenced obviously by John Ford, and John Ford was tremendously influenced – it’s there all the time – by D.W. Griffith, and D.W. Griffith was a child of Dickens.

All I’m really trying to say is that we are all connected; we all, to some degree, borrow a bit or are influenced by. The real question isn’t that. The real question is do you develop your own voice and your own artistic personality? That’s what’s critical and important. And that we have to leave for others to judge.

LMD: Thinking back to what you said to about Ms. Rodriguez, she definitely has a quality that seems common to your actors. Whether it is Charles Bronson, Nick Nolte, Willem Dafoe, Mickey Rourke, Jeff Bridges, Ian McShane, Ices T and Cube, your actors have a presence and gravity that leaps off the screen, which seems very rare these days. I feel like Michelle Rodriguez is a straight line in that connection to those stars. Is there a commonality or a specific quality you seek in your actors?

WH: Well, I would just say I agree with you, but how I would define it is I think it’s more instinct than it is intellect. And you say to yourself, ‘Yeah, that’s what I’m looking for. This person has it. This person’s got that quality that’s almost indefinable.’

LMD: And you’re able to see that through their auditions and previous work?

WH: Yeah, we meet, we talk. And not even so much through... I’m not the world’s greatest believer in auditions and line readings, and all that, because the condition is, somebody comes in with a script in their hand and stands there in your office, and they may be skillful, or whatever, but it’s so different than what it will be under photographic conditions on the set, knowing you already have the part, knowing you are the character.

So, I think what’s really interesting to me when I meet people is the assessing. You’ve usually seen them in some form or another on film, but it’s the assessing of their character and ways you think you can reach down for, reach inside them for. It’s that assessment that becomes the critical thing. And again, I think the answers are more instinctive than intellectual.

LMD: I’ve read that THE ASSIGNMENT is your first independent film.

WH: Well, technically, I don’t think that’s true. Undisputed was an independent film. Southern Comfort was made as a negative pickup deal. Seems like there was some other one in there that I can’t remember, but anyway, technically, I don’t think that’s quite true.

LMD: You’ve said that every film you’ve made is essentially a western. What are the western elements in THE ASSIGNMENT?

WH: Well, it’s people who find themselves in a moral dilemma and moral attitudes, and they must work their way through the problems themselves, beyond the scope of normal, civilized social behaviour or organisation. In other words, they don’t turn to the government for solutions. I mean, look, this is a crime story, where the cops are not even a part of the story. You see some flashing red lights after some of the goddamnedest mayhem, but that’s it for police organisation.

The tale plays out with the conflict between the characters in a very primal… It’s the primacy is what I’m trying to say. I always say that when you make a western, there’s all this stuff about you’re in beautiful country, usually, around the horses, which are very inspiring to be around. Somehow, I think the horses make everybody behave better.

I’m not sure why, but it just seems to work that way. And the costumes, and it’s all fun, and of course you’re part of one of the great traditions of American movie storytelling, the Western. It’s fun to be part of all that. But in a deeper way, I’ve said this several times to people, it’s really like you’re walking around in the Old Testament. You’re telling Old Testament stories, which can be seemingly simple but very complicated. And in a way, I think you can say The Assignment is an Old Testament story.

LMD: You co-wrote {with David Giler} the story for ALIENS, which made a star of the late, great Bill Paxton, who you directed in STREETS OF FIRE and TREPASS. Would you please share a memory of Mr. Paxton?

WH: Oh, gosh, I think I’m gonna… I loved him as an actor, I loved him as a friend. Bill, I can’t believe that he’s passed. I was at his memorial service. Two weeks ago today, they had a beautiful service for him out at Warners, where they showed clips from his movies and people spoke. Sigourney spoke.

I last saw Bill - it turned out to be in a sense prophetic - I didn’t know he and I had the same doctor. I was in the doctor’s office getting final clearance; I had a flu and it had gone to my lungs – I have Irish lungs - when the cart me away for the final time, that’ll be what it is. Anyway, I was clearing up the cough and Bill stuck his head in the little room I was in, and it was “Hey buddy, how are ya?” And I hadn’t seen Bill and a couple of years. You know, one of the qualities that Bill had, you might not see him for year and a half, and I’m telling you, 15 seconds after you started talking to him, it was like you had seen him every day for months. He had a way of picking up a relationship and just carrying on.

He had an extraordinarily positive personality; he was very smart. A lot of people don’t know this, he was very expert about contemporary American art. He had quite an art collection, himself. He bought sold and traded within that world.

He got that from his father, who I also had the good fortune to know. Actually, his father worked for me on Last Man Standing, he played a small part, and Bill used to come out to the set so many times to see his dad. Bill and his dad were very close. I always thought it was funny, this lumberman in Fort Worth, Texas had this deep appreciation of American art, and Bill got it from his father. When Bill came out and really started working as an actor, his father retired not too much after that and moved to LA…

I don’t know what to say, really. He left behind a beautiful family. He left behind a body of work that I think is going to last in the mind of the audience that experienced it. He left behind an awful lot of friends. We were all the better for having known and worked with him.

LMD: What might our readers have to look for from Walter Hill after THE ASSIGNMENT?

WH: I think I do know what I’m doing next. It’s going to be announced in about a week, but I’m not supposed to say. But I am optioning a play that was done here in New York, and I’m going to be working on the screenplay with the playwright, so that will be announced shortly, as well.

I’m not quite ready to hang it up. {Laughs.}

THE ASSIGNMENT opens in US cinemas on April 7. It is also available to watch via various Video On Demand platforms.

This interview is cross-posted on my own site, The Diva Review. Please enjoy additional content, including exclusive photos there.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.