Review: SNOWDEN Means Well

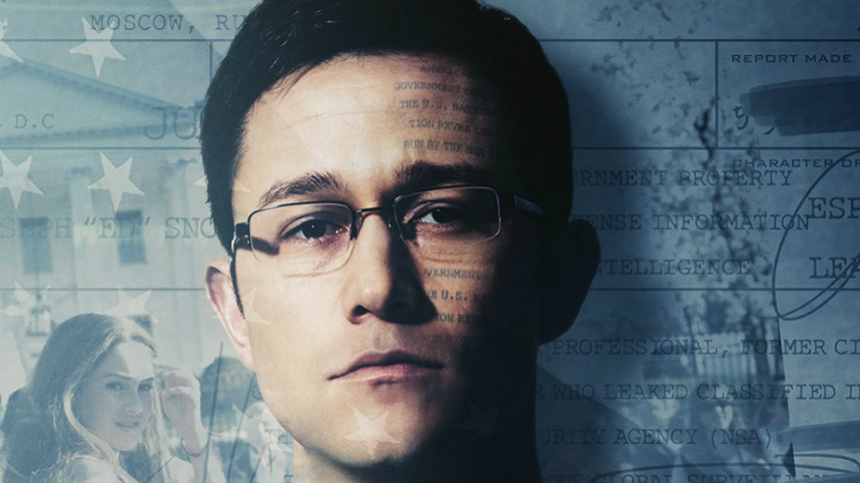

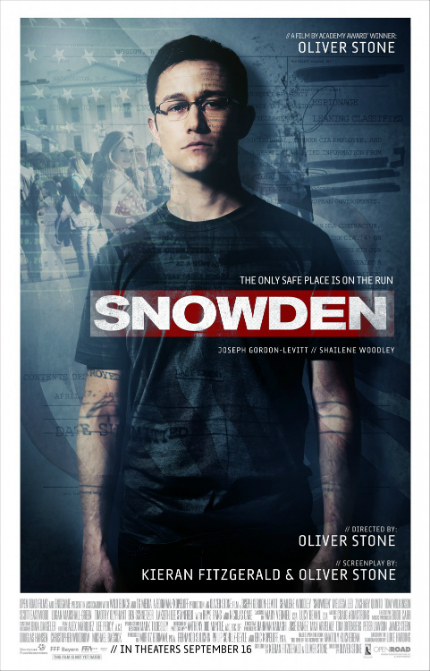

Sturdy and sincere, Oliver Stone's Snowden is an admirable ox, intent on delivering a warning message about the dangers of the U.S. government and its surveillance program upon its own citizens. Simultaneously, the film diligently and respectfully canonizes Edward Snowden, who is humbly portrayed by Joseph Gordon-Levitt as the bravest and most brilliant man in the world.

In so doing, Stone has made his first superhero movie. He's done it in the more restrained visual style that has marked his work since Alexander (2004), with fewer visual tics and tricks. Snowden is, more or less, a straight narrative piece, telling the life story of its titular character, beginning in 2004 with his attempted service in the armed forces, which is cut short during his training due to physical problems. (Even there, it's a foregleam of his superpowers, as it's shown that he's been training on two broken legs.)

In 2006, Snowden applies for a job with the C.I.A., where he is hired and quickly distinguishes himself as a computer analyst. He is recognized as the top student in his class and is mentored by his instructor, Corbin O'Brian (Rhys Ifans). He also befriends Hank Forrester (Nicolas Cage), a brilliant computer expert who designed a system that his superiors did not like, sidelining his career and leaving him to work by himself. Naturally, that's a foregleam of what will happen to Snowden.

Corbin likes Edward so much that he sends him to begin his career in Switzerland, where his top-notch skills are not terribly appreciated by his superiors. Edward's desire for field work leads him to begin working eagerly with a CIA operative (Timothy Olyphant), whose dishonest, distasteful methods sour Edward on the CIA, prompting him to resign.

As his intelligence career is experiencing ups and downs, Edward strikes up a relationship with Lindsay Mills (Shailene Woodley). Their relationship has its own ups and downs, owing largely to Edward's requirement to keep his employment details strictly confidential. Much of the movie bounces between their oft unhappy private life and Edward staring at computer screens.

Beyond the strict secrecy, Edward feels honor-bound to devote himself to the work that he is doing, which begins to tear him apart as he becomes aware of the full extent of the government's intrusive intelligence operations. The emotional and mental toll is enough to drive any ordinary man to drink or drugs, but Edward doesn't do either. He can't unload his conscience to anyone, especially his companion.

Beyond the strict secrecy, Edward feels honor-bound to devote himself to the work that he is doing, which begins to tear him apart as he becomes aware of the full extent of the government's intrusive intelligence operations. The emotional and mental toll is enough to drive any ordinary man to drink or drugs, but Edward doesn't do either. He can't unload his conscience to anyone, especially his companion.

Yet he feels compelled to remain because ... well, no one else can do it but him, at least in his view. Thus, Edward faces what might be called the superhero's conundrum, except that this is a real-life, ongoing dilemma. As portrayed in the movie, he's not trying to save people; he just wants everyone to know what's going on and be able to make their own decision about what information is made known publicly to the government.

Freedom of choice is a fundamental right of human beings -- unless, perhaps, you believe in destiny -- and so it's easy to get behind the message that the film delivers, over and over and over again. Much less time or attention is given to the reasons why that matters in today's society, in which it seems that we're being asked to give away private information on a daily basis, if not to governments then to corporations.

Oliver Stone's best films, such as Platoon, Wall Street and JFK, have proceeded from similar, impassioned, and singular perspectives. That's been balanced, though, by his dynamic filmmaking skills; even if you didn't agree, understand, or sympathize with a particular viewpoint, the movies were compelling dramatic experiences. Even his uglier, more emotionally rancid experiences (Talk Radio, Natural Born Killers, Nixon, Any Given Sunday) were fascinating to behold because of the passion that drove them.

As thematically potent as Snowden is, the restraint and respect limits its impact. One scene late in the movie, featuring a looming and ridiculously large face in contrast to a very human-sized body, feels like the Stone of old. But otherwise, the movie too often feels flat and formulaic, more like a dramatic interpretation than a vivid reimagining.

The more essential and vibrant commentary on Edward Snowden remains Laura Poitras' Citizenfour, which features vital eyewitness footage that Stone can only try to emulate. Snowden is a worthy endeavor, filled with good intentions and righteous feelings, but it flies lower than Poitras' finely-cut documentary.

The film opens in theaters throughout the U.S. on Friday, September 16.