Ariel Kleiman Talks PARTISAN: "I Find Mystery And Cinema A Magical Combination"

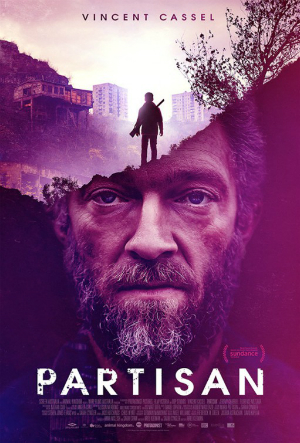

Vincent Cassel stars in Partisan as the charismatic leader of a commune sequestered on the outskirts of a small town. That makes him a formidable figure to his son, Alexander (Jeremy Chabriel), who from outward appearances is just like any other kid, except that he's a trained assassin. Their inevitable conflict forms the dramatic core of Partisan.

Ahead of its theatrical release in the U.K. this week, director and cowriter Ariel Kleiman (above) talked with us about working with a famous star as well as a young cast, his possible influences, and what he hoped to achieve with the film.

ScreenAnarchy: What does it mean to you as a first-time feature filmmaker to have somebody like Vincent Cassel come on board?

Ariel Kleiman: Oh, it's huge. It certainly added a whole other level of validity to our project. It kind of strengthens the whole thing up.

You know, the hardest thing for me when I'm making a film is just getting out of bed in the morning [laughs] because I like to sleep! But having somebody like Vincent join the project definitely gives you an added incentive to get up.

What was he like to work with, was it quite intimidating?

For me, there was an intimidation factor, because previously, with every film I'd made, casting was a very big part for me, and part of the casting process had often been to really try to hang out with the actors too. That way I always felt I could get to know them as people, and that certainly helps when you're directing them. But that was very difficult in this case, because Vincent was busy over in France.

So this time it was a bit of an unknown. It was kind of like, erm... experimental alchemy. In terms of his chemistry, it was like I didn't really know how he would be to work with or what his chemistry would even be like with the other actors.

So how did you get round this?

Well, he was kind enough to come a week before the shoot, and that allowed us to hang out a lot. I'd say I basically acted as his chauffeur. [Chuckles.] So I would just drive him around lots, and in reality that was huge, because by the time we got on set, we already had developed a kind of bond. By then I'd say we both knew where we were coming from, and it made working together really easy. Working with him was a dream actually.

What about working with such a young cast, what was that like?

Yeah, the thing with that is that Sarah Cyngler and I write these films quite naively. Then later on it dawns on me what we've done, because I'm the one that has to direct it. I always end up faced with this realisation of how it's going to be to make, but on this film I actually loved working with the kids.

Kids are just so natural. You can put the camera right on their face and they'll just act. They're not self-aware like adults, they don't have all these kinds of acting "ticks" or anything like that. They're just so pure, and a lot of the time that means they're either really good or really bad. I find that makes their performances really easy to edit, too.

But I've got to say that in general -- I mean, of course every kid is different -- but in general the girls were lovely to work with. They were very professional and very easy-going. Whilst some of the boys... [Laughs.] They were... more eccentric.

Do you think you regret any of your casting or directorial decisions with retrospect?

Do you think you regret any of your casting or directorial decisions with retrospect?

I don't think so. I mean, with every film you make, there's always a million regrets, but I always just try to go by the belief that if I'm true to myself then that's enough, because that's all you can really do as a director.

So in a way, I also have zero regrets, because I feel like, moment to moment, I was pure and true to the story - but yeah, if you really start thinking about it, it's way too depressing! [Laughs.] That's why you think up things like that: to make yourself feel better.

It does seem like lots of independent filmmakers are opting to work with very young casts at the moment: films like Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz's GOODNIGHT MOMMY, Robert Eggers' THE WITCH, Deniz Gamze Ergüven's MUSTANG and Martin Zandvilet's LAND OF MINE. Why do you think that is?

Well... I can't speak for the other filmmakers, but maybe in general it has more to do with the fact that if you're making your first or second feature film, you're probably still pretty close to those memories of childhood yourself. Certainly, I know that that acts as the inspiration for a lot of short films. A lot of them use child actors and focus on stories about growing up.

Interestingly enough though, I'd never made a story like that yet. I'd never made a story about growing up in my shorts. They were always much more about adults, so in some ways I suppose it's kind of actually a little clichéd doing a coming of age film as your first feature. [Laughs.] I guess I've never fully thought about it that way, though.

Childhood is definitely an incredibly dramatic and nostalgic moment in everyone's lives, though, and in many ways it shapes the adult you become, so I can definitely see why it would be a period of life that interests so many filmmakers.

And was your film influenced by other Australian coming of age stories such as SNOWTOWN at all? I suppose that has a similar kind of slow grooming process going on in it.

Yeah, totally it does, but it wasn't like a direct influence or anything like that, though, when we were making Partisan. By the time Snowtown came out, and we'd seen it, we were already well into writing our film, but yeah, there's totally a similar father-son, highly questionable relationship at the heart of both films.

I suppose with SNOWTOWN, though, it was very apparent how that film directly addressed social issues that are present in Australia. Do you think your film still does that too?

You know, I don't think our story is really any more about Australia than it is about any other country, and it was kind of intentionally devised that way.

We had an African character, there's an Argentinian, there's also a woman from the Middle East. For us, creating this hodgepodge of ethnicities was actually really important, because we'd dubbed the world in this film as a kind of "nowhere land." That said, when I was living in London, it felt so diverse, that I don't think this world we created is actually that farfetched. It's the same thing with Melbourne, you get this incredible mix of ethnicities.

But the film is actually set in Georgia, is that right?

No, we just used Georgia for exterior locations, so we could get the kind of look and feel that we were going for. But in our minds, the film really was set in this kind of "nowhere land" or this kind of middle Europe at most.

Why made you decide to make it that way then? Just so you could be more universal?

It was a financial decision. [Laughs.] No, basically from the very start I wanted to set this film in a kind of impressionistic world. I wanted to let the audience know as much as possible that this was not a story that is meant to be understood literally. It was conceived more as a fable. It certainly isn't a realist painting, it is an impressionistic painting. That kind of thinking was a big inspiration to a lot of my filmmaking decisions.

Generally speaking, anyway, I really despise when films overload me with information or effectively treat the audience with disrespect by spoon-feeding them information. I feel that we already live in such an Information Age that often there's so little mystery left in the world, and I find mystery and cinema a magical combination. I mean, I'd say I have no idea what some of my favourite films were about, because the first time I saw them they were complete enigmas to me.

For one reason or another, though, those films still got under my skin, and that kind of effect is certainly one element of cinema that I love.

So is it very important for you to force your viewers into an active process of interpretation with your film?

Definitely. I'd say that early on we were very passionate about the fact that we wanted to tell the story from Alexander's emotional perspective. So a lot of the script decisions and the decisions made throughout the shoot were inspired by that. I guess I wanted to put the audience in Alexander's shoes first and foremost.

In many ways he grows up just like most other kids do: with blinkers on. It's only when you start to grow up that your blinkers widen, and I wanted to recreate that. I wanted to suddenly put blinkers on the audience, and rob them of knowledge of context and in that way really put them in his shoes. I guess the film definitely raises more questions than it gives answers.

But in the film, moment to moment, we only know what Alexander knows, and that's the journey I want the film to take you on.

Partisan opens in select U.K. theatres on Friday, 8 January.