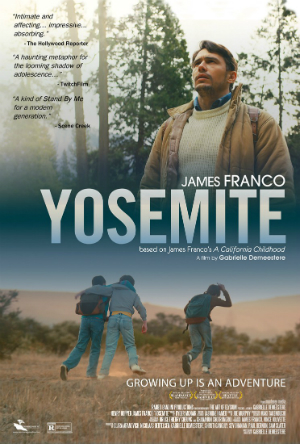

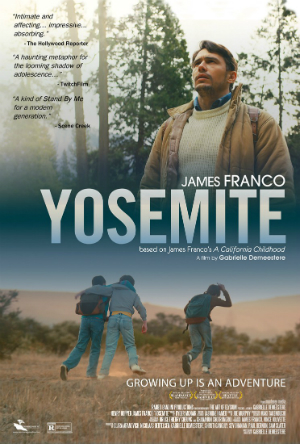

Review: YOSEMITE, Childhood Is Always Now

Gabrielle Demeestere's pivots such feelings and moods, intangible, strange and so wonderfully potent, with her feature debut Yosemite. Set in the fall of 1985 in the ever-expanding Palo Alto, California, the film charts the intertwined stories of three 5th grade boys: Chris (Everett Meckler), Joe (Alec Mansky) and Ted (Calum John).

We begin with Chris, who goes on a weekend trip with his father (James Franco, who also executive produced through his Rabbit Bandini Productions) and little brother to Yosemite National Park. As the boys prepare for their first hike, the news on the radio talks of mountain lions invading human territory. Towns are on high alert.

An ever encroaching natural world, fierce and different, colliding with the pleasant suburban living of Northern California emerges as a haunting metaphor for the looming shadow of adolescence. Of that something new and unknown. This unsettling feeling sits comfortably in the background of the film's 82 minute length, never upending the gentle and intimate narratives of the boys' lives into something sensational or crass. On their hike, Chris finds a carcass burning in a fire. Is it a bear? Is it a man? It is encounters such as this that help give a rich sense to Demeestere's film but not an obvious definition.

The second story follows Joe, Chris' classmate, a quiet child who makes friends with Henry (Henry Hopper), a young man who invites him over to read aloud his comic collection. Their relationship sits in that spot that is just as sweet as it is alarmingly uncomfortable.

The second story follows Joe, Chris' classmate, a quiet child who makes friends with Henry (Henry Hopper), a young man who invites him over to read aloud his comic collection. Their relationship sits in that spot that is just as sweet as it is alarmingly uncomfortable.

Our final story, which eventually ties all three boys together, follows Ted, who at one time had been close friends with Joe. The game Ted insists playing in class, where they pinch each other's penises under their desks results in Joe stabbing his friend with a pencil to the brow. As the threat of the mountain lion becomes all too real, Chris and Ted bond a little closer, while at nights Ted talks to his dad, a computer engineer and insomniac who chats to people over a proto-internet.

Through these boys' tenuous friendships and their own loneliness, Demeestere demonstrates a deft touch working with child actors. All three boys give exceptional turns, each distinct in their desires, their fears, while certain big questions haunt them all. The specter of death, signifying change, runs its scythe across each frame. Reoccurring images of feet being cleansed by water and prayers being whispered creates a subtle tapestry between all three stories that doesn't pronounce the film to have faith, but gives it a melancholic purity which clenches the heart.

Joe Murphy's editing is careful not to intrude and manipulate too heavily on the boys' inner worlds. His cuts instead are guided by letting the boys' own small gestures lead the rhythm. This is also the general consensus behind the camera with cinematographers Chananun Chotrungroj and Bruce Thierry Cheung, who lens with an indecisive, half-light as much as possible. This results in the film feeling both ever eternal, frozen in that golden moment of boyhood, and with that uncertainty, that newness, creeping up.

When the boys decide to go and hunt a mountain lion on the outskirts of town, one might expect the movie's mood to suddenly shift to something more like Stand By Me, an adventure yarn inflected with rosy if cynical nostalgia. But it is Demeestere's choice to keep it of the moment that creates the film's ultimate resonance. For while Yosemite may take place 30 years ago, it is Now on screen. Childhood is always Now. These boys are just living their lives in wonder and pain. There is wisdom in that, I think. A wisdom that few filmmakers working with childhood stories seem to tap into.

Céline Sciamma did it with the sexual malady of Tomboy, and now so has Demeestere with Yosemite. It's a mature debut that firmly plants the director as a phenomenal talent to watch.

The second story follows Joe, Chris' classmate, a quiet child who makes friends with Henry (Henry Hopper), a young man who invites him over to read aloud his comic collection. Their relationship sits in that spot that is just as sweet as it is alarmingly uncomfortable.

The second story follows Joe, Chris' classmate, a quiet child who makes friends with Henry (Henry Hopper), a young man who invites him over to read aloud his comic collection. Their relationship sits in that spot that is just as sweet as it is alarmingly uncomfortable.Our final story, which eventually ties all three boys together, follows Ted, who at one time had been close friends with Joe. The game Ted insists playing in class, where they pinch each other's penises under their desks results in Joe stabbing his friend with a pencil to the brow. As the threat of the mountain lion becomes all too real, Chris and Ted bond a little closer, while at nights Ted talks to his dad, a computer engineer and insomniac who chats to people over a proto-internet.

Through these boys' tenuous friendships and their own loneliness, Demeestere demonstrates a deft touch working with child actors. All three boys give exceptional turns, each distinct in their desires, their fears, while certain big questions haunt them all. The specter of death, signifying change, runs its scythe across each frame. Reoccurring images of feet being cleansed by water and prayers being whispered creates a subtle tapestry between all three stories that doesn't pronounce the film to have faith, but gives it a melancholic purity which clenches the heart.

Joe Murphy's editing is careful not to intrude and manipulate too heavily on the boys' inner worlds. His cuts instead are guided by letting the boys' own small gestures lead the rhythm. This is also the general consensus behind the camera with cinematographers Chananun Chotrungroj and Bruce Thierry Cheung, who lens with an indecisive, half-light as much as possible. This results in the film feeling both ever eternal, frozen in that golden moment of boyhood, and with that uncertainty, that newness, creeping up.

When the boys decide to go and hunt a mountain lion on the outskirts of town, one might expect the movie's mood to suddenly shift to something more like Stand By Me, an adventure yarn inflected with rosy if cynical nostalgia. But it is Demeestere's choice to keep it of the moment that creates the film's ultimate resonance. For while Yosemite may take place 30 years ago, it is Now on screen. Childhood is always Now. These boys are just living their lives in wonder and pain. There is wisdom in that, I think. A wisdom that few filmmakers working with childhood stories seem to tap into.

Céline Sciamma did it with the sexual malady of Tomboy, and now so has Demeestere with Yosemite. It's a mature debut that firmly plants the director as a phenomenal talent to watch.

Review originally published during the Slamdance Film Festival in January 2015 in slightly different form. The film will open theatrically in New York on Friday, January 1. Further theatrical play dates will follow in the U.S. Check out the film's official website for more cities, including Los Angeles, New Orleans and Wilmington.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.