HOUSE (1977)

This is where it all starts, both for Obayashi's feature filmmaking career and for most of those outside Japan encountering his work for the first time. It's a wild, anarchic take on the haunted house movie, incorporating ideas from his young daughter Chigumi, and freely using techniques employed in the many experimental films and TV commercials he'd made before then. A group of young girls, with such evocative monikers as Gorgeous, Sweet, Melody, and Kung Fu, are invited to a house that begins to eat the girls, one by one. From today's perspective, House can be seen as an ode to pre-digital filmmaking, its fun atmosphere created largely by practical and in-camera special effects. While Obayashi's subsequent features would dial the craziness way down, he would continue to incorporate his experimentation into more conventional structures that nevertheless retained a fresh, exploratory spirit.

I ARE YOU, YOU AM ME (aka EXCHANGE STUDENT) (1982)

This Freaky Friday-esque comedy concerns two teenagers, the boy Kazuo (Omi Toshinori) and the girl Kazumi (Kobayashi Satomi) who fall down a set of stairs and magically switch bodies. The gender-swapping complications play themselves out in a much earthier and more bawdy way than any Disney movie would, or could. The film is part of a trilogy set in Obayashi's hometown of Onomichi, and it fits into themes of nostalgia that recur often in Obayashi's work. Here, love is engendered by living in another's skin and fully understanding the feelings of the other, a message clearly dear to Obayashi, philosophically and politically a committed pacifist.

BOUND FOR THE FIELDS, THE MOUNTAINS AND THE SEACOAST (1986)

The opening titles declare this to be "A MOVIE CLASSIC." It's a description that's simultaneously tongue-in-cheek and quite accurate for this WWII-era drama that evokes the classic films made at Shochiku studios by Ozu and Hiroshi Shimizu. A group of young kids replicate the larger war with a miniature one of their own, but eventually get together to try to save a young girl (Washio Isako) from being sold into prostitution. There are two versions of this film, in color and in black-and-white; only the color version is currently available. But even in color, the qualities of homage and honoring past masters remains potent. Obayashi injects a playful, even cartoon-like sensibility - most notably with the comic antics and expressions of the teacher played by Takeuchi Riki - with his potent critique of imperial Japan's increasing appetite for destruction.

THE DISCARNATES (1988)

A lovely film that uses elements of fantasy and the supernatural to explore its themes of nostalgia, The Discarnates concerns a TV drama writer (Kazama Morio) who, while researching a project, visits the Asakusa neighborhood of Tokyo where he grew up. There he encounters his parents, who had died in an accident when he was 12. They appear just as the had in the late 50's of his childhood, and he makes frequent visits to them, reliving this time as an adult. Meanwhile, he has an affair with an alluring, mysterious neighbor (Akiyoshi Kumiko), after she first visits him with a bottle of champagne, wishing to be relieved of her loneliness.

This film is simultaneously a love story, a ghost story, a time-travel tale, and a zombie movie. Some of Obayashi's most poignant, loveliest images can be found here: rain falling in an apartment building's corridor; two ghosts disappearing as they bid farewell; a long-wished for game of catch between the writer and his father. Horror, the fantastic, nostalgia, and sensuality combine to create an exhilaratingly beautiful atmosphere.

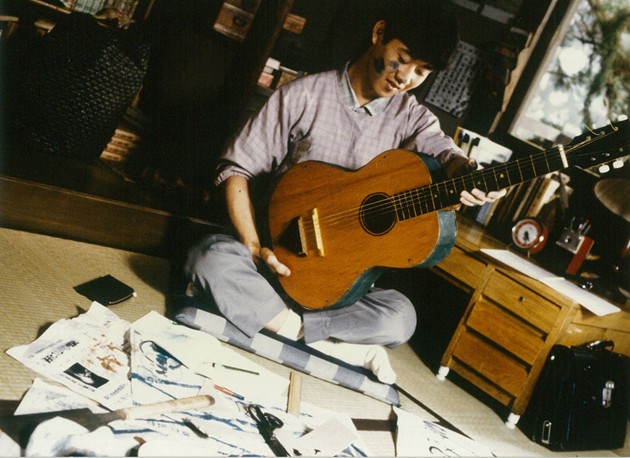

THE ROCKING HORSEMEN (1992)

In 1965, a high-school student (Hayashi Yasufumi) discovers the Ventures' rock instrumental classic "Pipeline" one day, and immediately ditches his classical music training to pick up a guitar and form a band. The basic elements are quite standard - a coming-of-age story, a music movie, a man looking back on his past - but as usual, Obayashi manages to make it all not so ordinary. With a restless, fast-cutting camera, Obayashi immerses the viewer fully into its period, but also takes us beyond it, with flash-forwards, direct addresses to the camera, and other techniques that depict time as not a linear straight line, but as a continuum that flows in all directions. Again, nostalgia is very much present, but here it's suffused with poignancy and anxiety. The protagonist wonders if the glory days of high school will be the peak of his existence, and if afterward all that's left to look forward to is a life of arid mundanity.