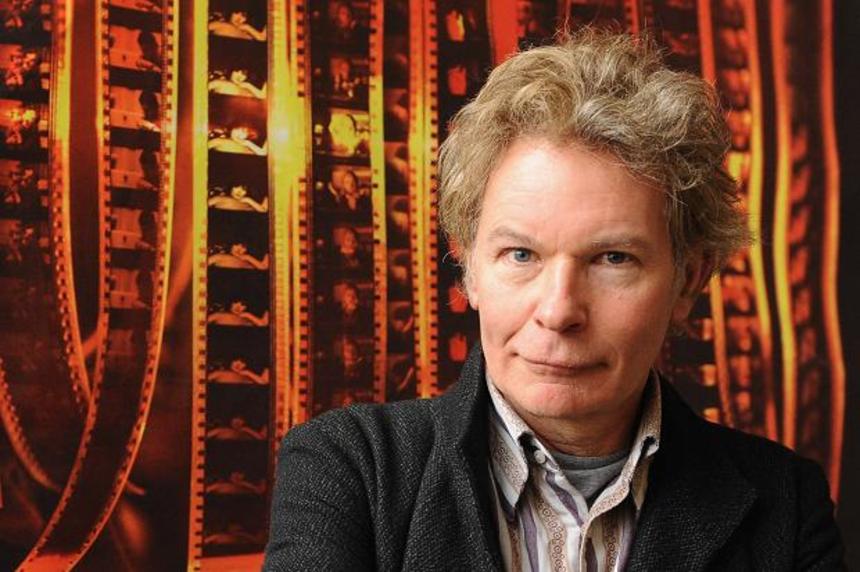

SXSW 2015 Interview: Julien Temple On Life, Death, And THE ECSTACY OF WILKO JOHNSON

The project arose upon receiving the tragic news that his good friend Wilko Johnson, former Dr. Feelgood front man, had been told he had only 10 months to live. His initial interviews with Johnson had less to do with making a film than they did documenting the final testimonies of a true rock great.

But what Temple quickly learned of his friend was that Johnson wasn't about to sulk in his fate, nor did he intend to seek medical treatment. "Just because I'm dying doesn't mean I have to be bored by it," Wilko tells Temple of his decision to disregard doctors' recommendations for lengthy procedures in favor of embarking on the world's most literal farewell tour.

For a funny thing happened to Johnson upon hearing the grim news. Rather than being burdened by a crippling sense of death, Johnson was instead gifted with an elating sense of life, offering him a rare perspective and an overwhelmingly beautiful dose of presence. This is Wilko's ecstasy and it's infectious.

Inspired by his mate's amazingly brave attitude, Temple's documentary shoots for nothing short of life itself in the punkest fashion. With its meditatively free-form editing, which borrows great sentiments on the grandiose theme from Bergman, Cocteau, and Buñuel, and a bevy of poetry from thinkers like Blake, Chaucer, and Milton, Ecstasy is an unpretentious middle finger to the reaper. Never has a rockumentary aspired to more and, consequently, Johnson's tribulations and their resulting film are a true marvel that ought to be mandatory viewing, not just for rock-aficionados, but also for the world at large.

ScreenAnarchy: How did you first discover Wilko's tragic news?

Julien Temple: I didn't hear directly from him, I heard from... I'd made a film Oil City Confidential about his band Dr. Feelgood a few years before, so the people I made that with knew before I did and they told me. It was very horrible to hear that news but I certainly didn't think I was going to make a film about that process until much later.

Everyone knew he was supposed to have 10 months to live and obviously the film is about this journey, but he just kept going and after 10 months he was still playing and it was this weird kind of Gospel type thing. They were in tears and waving goodbye and thinking that was the last time they're ever going to see this guy who they loved, and then two weeks later he'd be doing another, like Frank Sinatra, doing another farewell tour.

After a while I called him because I know him. We got on very well on the other film so I'd spoken to him about the idea of 'would you like to talk about it?' He said, "Yeah, come down." He was quite open to having a camera.

When you first spoke with him about it, did his brave perspective jump out at you? How had he been treating that conversation with friends?

It was very weird ... You knew you were in the presence of someone who was on a high, like a weird rush of feeling in this man. It was something I didn't really expect to feel but it was quite uplifting. For me, my mother was dying and there was a good energy and that's what was... The thing that made me feel there is perhaps a film in this is because his response to it is not what you necessarily would expect to see.

At the SXSW premiere, you'd mentioned that a lot of the film clips and poetry passages included in the film came to you while you were ruminating about life and death in the dead of night... Can you describe that free association process?

The nighttime is a weird time, isn't it? ...For the mind. I have a history of sometimes having a really bad time not being able to sleep and then I have really good times where I'm half asleep and I seem to be able to control images and thoughts in a really subtle way that I can't do when I'm totally awake.

When you're lying there dwelling on this and you're recalling the conversations that you've had and your feelings, it's quite easy to coax your mind back to these images. A lot of them are from very early days when I connected with film. I used to go to this place on Portobello Road called The Electric -- it's still there. It's totally changed now. In those days, you had fleas effervescing in front of the screen, diving off the seat in front and you'd see the screen through this burst of jumping fleas. There was another great cinema where all the tramps in London ended up sleeping in the aisles and between the seats, trying to steal your shoes while you were watching these art films.

It got so bad in this one place, the roof was falling in, and so you'd see the film with snow falling in front of the screen; a Luis Buñuel film with snow falling is a very beautiful thing.

I can imagine Cocteau's BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (featured in ECSTACY) would be pretty enchanting under those circumstances.

It's going back to those kind of feelings. When you first connect with a medium as powerful as cinema, it's a very powerful thing, so I was drawn in that way to look at films that dealt with mortality and some of the themes that Wilko was expressing.

Can you talk a bit about the editing process and connecting Wilko's words to images?

I mean he always struck me way before this as being in the tradition of William Blake, who spoke with a thick Cockney accent like Wilko. It's not a voice of ... In England anyway, you kind of expect poetry to be delivered in a bourgeois voice, more like my voice, right? William Blake spoke like Wilko and I wanted to make that clear that poetry doesn't come in one voice, one accent. It doesn't belong to one class of people.

There was always this weird visionary side to Wilko. You can hear it even in some of his lyrics. There's a beautiful song called "All Through the City," which is about Canvey Island off (Dr. Feelgood's) Down by the Jetty and he's talking about the burning towers of the oil refineries. It's kind of a visionary thing, so I knew he had that aspect in him, but I didn't really realize how deeply rooted in a kind of literary dimension this guy is.

It's quite magical because he throws weird quotes into very everyday conversations and you don't know where... They could be from Chaucer or they could be from Milton or Spencer or Coleridge or... It's kind of random, incoming quote missiles, which is quite a nice thing to be able to do, I mean I wish I could do it. I can't remember in the way that he can.

One of the many quotes that jump out at me - I think it was Blake - it was something like, "You don't know when you've had enough until you've had too much of it."

William Blake, good old William Blake.

I think it was in and around a section that discussed "the road of excess leading to the place of wisdom..." I was thinking about these types of perspectives in rock and roll and in punk and I wonder if that would be an accurate description of these kinds of characters that you seem to admire very much.

Yeah, I think so. I think my filmmaking style is also ... It's to do with acid, as well. I took a lot of LSD, like Wilko at that time, when I was growing up, that was the thing to do.

A lot of people got damaged by taking too much of that stuff and I was lucky that I didn't and so was he, I guess, so I shared that background with him, as well as the literary background and a rock and roll background, so there were a lot of things that converged between me and him that kind of sparked off each other in a good way.

Perhaps this is a non sequitur, but on the topic of LSD, I'm wondering where you come from on something like 1966 The Grateful Dead. Do you recognize any punk roots in the acid tests?

I don't have a problem with the early hippie ethos. I did, as a punk, want to get rid of that stuff because it'd started to putrefy by the time I was around, but in retrospect and with hindsight you clearly realize that the pure meaning of the early hippie era was just another station of the mind, and it's a good thing.

I really like early psychedelic music, too. I don't have a problem ... I saw The Doors when they were at the Roundhouse, dressed in a gorilla suit. I had this gorilla suit from Morgan - A Suitable Case for Treatment, a famous '60s London film. I knew the daughter of the costume person and somehow I got this gorilla suit, which, at the time was kind of state of the art.

People would look at it and think, "Fuck, it's a gorilla," so it was kind of good being 13 in this gorilla suit at the Roundhouse because they thought you were some massive weird freak, you know hippie, I don't know, they didn't know what was inside the suit. It was actually a 13 year old kid. Which was good. I used to hang out on the top of the bus trail outside the zoo and freak people out.

Of the many things that Wilko said to you in the course of your filming him, are there one or two bits that really resonated as lessons imparted by Wilko, which you'll never forget?

The thing that I find quite miraculous was... he said this thing of not committing things to memory anymore... I've heard a lot about living in the moment and all that stuff but this idea of divesting yourself of the need to remember seemed pretty extreme. Yet I did get the sense he was doing that weirdly. There were some times when he would say the same thing again having completely forgotten that he'd said it. Not in a kind of dementia like way but this kind of rinsing of the mind that he seemed to get into

I've never been able to do that. I think I'm remembering this conversation now... You forget things, obviously, but that I don't need to remember, or need to waste the chemical reaction of remembering. It was interesting.

For somebody who isn't so familiar with Dr. Feelgood or Wilko, what would you say are your top 3 desert island Wilko tracks?

That one, "All Through the City," I love that because it's got that kind of visionary side in the lyrics. I love, "Back in the Night" and "Going Back Home" is a great song, too. There are so many good songs. I really like "Malpractice," the second record.

As somebody who's had a great life of seeing live music, and documenting music, I'm curious about what would you would say are sort of the top shows of your life that you'll forever look back at as the ones that blew your mind?

Definitely seeing The Sex Pistols was a big thing for me. I saw The Kinks very early on at Marquee...

What year would that have been?

Would've been like '65, something like that. Yeah. I saw the Stones at The Albert Hall - that was great - in '66. Hendrix. I saw a lot of good things. The early Clash gigs were great. I enjoyed the Stones at Glastonbury, where someone gave me way too much MDNA, right back in the day there. It was great. I thought the concert had gone on for 10,000 years, but it had just begun. Fantastic feeling.

What would you say made you want to be a documentarian or "rockumentarian." Not that that's all you do, of course.

I hate the word, "rockumentarian".

Fair enough. Filmmaker.

Filmmaker? I'm called "filmmer," Not "filmmaker." That's the Somerset term, which is where I'm from - filmmer. Filmmer lives up the road, "that weird filmmer." I like to be known as "that weird filmmer."

What started you on the path of being a filmmer?

I was studying architecture and I just got really bored with it and there's a place where you can watch lots of films so I just started watching loads of films on 16 mil, could watch 75 movies a week, which was good.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.