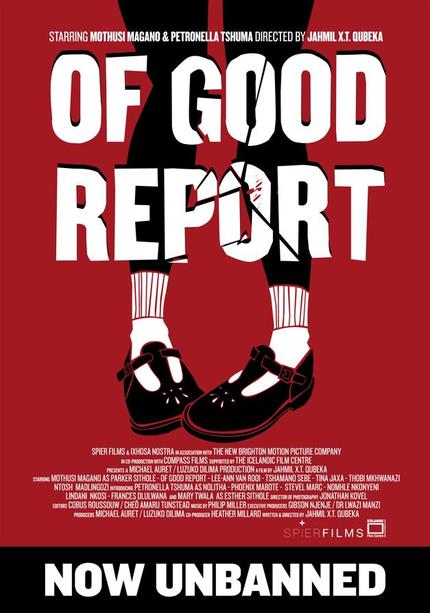

Durban 2014: OF GOOD REPORT, Revisiting Last Year's Banned Masterpiece

Of Good Report is an astonishing South African noir thriller -- I've never seen better South African film making -- about a teacher-pupil relationship that spirals into obsession and violence.

The film was selected as the opening film for the 2013 Durban International Film Festival (DIFF), and was scheduled to screen exactly one year ago today. Instead, on the eve of the festival, South African authorities banned the film for depictions of child pornography, the first such censorship of a South African production since the days of Apartheid. In hindsight the irony is heavy; Of Good Report is so obviously a scathing indictment of the very sexual predation that the censors used to justify its banning.

So why review it now, a year after the fact? Because the anniversary of the ban is a good time to reflect on how and why it happened. Because the opening night of this year's festival reminds me of the furore a year ago, though this year's opener, Hard To Get, is an action romance that shouldn't have much trouble with the censors. But mainly because I want people to know about this amazing film, and few people do.

The story about the film's banning is an interesting one, and I'll get into it, but it pales in comparison with the film itself; an edge-of-your-seat thriller that trips into dark comedy and descends into psychological horror with equal abandon. Mothusi Magano plays Parker Sithole, is an itinerant teacher who comes "of good report," but becomes involved with his young student, Nolitha (rhymes with Lolita, and played by sensational newcomer Petronella Tshuma), with tragic (read: psychotic) consequences.

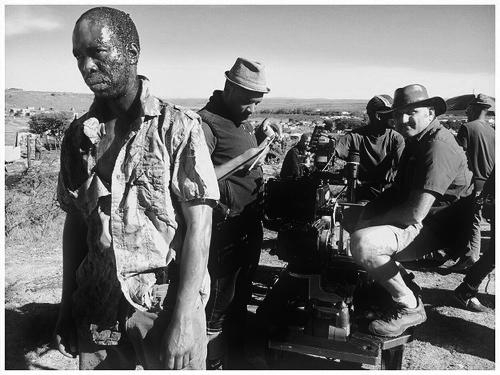

The black and white cinematography is mesmerizing, even if it does feel digital. It obscures the dark confines of Sithole's corrugated metal shack and hides the lurid colours of violence, but exaggerates the imagined grisliness. The film is disorienting and disturbing from the opening scene, and the absence of colour imbues it with a sense of something missing, something fundamental to normal reality. So too the protagonist, who has lost something fundamental to human normalcy, and exists in an increasingly disconnected reality.

Lead actor Mothusi Magano gives a bravura performance that left me impressed, upset, and uneasy at the end. It is astonishing that I feel the need to consider this spoiler territory, but I watched the entire film before ever realizing that Sithole doesn't utter a single word, ever. An occassional scream or laugh or wail, but otherwise utter muteness. It sounds like cliched reviewer gush, but its true nonetheless: Magano's eyes and expressions communicate his thoughts more clearly than his words ever could.

The direction from Jahmil XT Qubeka is rich in both its references and its originality, and very self-assured. It's impressive work from the young director, who only has a short and one other feature film to his name (Shogun Khumalo Is Dying! and A Small Town Called Descent, respectively). Qubeka puts the camera in Sithole's perspective during seminal disturbing moments, and uses the remarkable score and sound work to communicate Parker's thoughts and moods. Philip Miller and the sound department deserve special mention here for their intoxicating work, and not the happy kind of intoxicating.

If I rave about the standout performances of Qubeka behind the camera, and Magano in front, it is the ensemble acting that holds this film together, with half a dozen rich supporting characters filling in the silence and ramping up the tension. Mary Twala in particular gives an incredible performance as Parker's mother, Ester Sithole, which left my stomach viscerally wrenching at one point. Likewise, Nomhlé Nkyonyeni, Tshamano Sebe, Lee-Ann Van Rooi, and Tina Jaxa, all recognizable local actors, deliver subtle and sometimes hilarious performances. However, it is the innocent soul of the film, played by 23-year old newcomer Petronella Tshuma, who gives the entire fiction horrifying reality, and Tshuma's performance as the ~15-year old Nolitha is devastatingly good.

Though occasionally grisly, increasingly tense, and admittedly disturbing, the film is by no means ever pornographic, and the scene which triggered the ban was certainly very tame by modern measures of explicitness. Furthermore, Tshuma is a mother in her twenties, not a minor. It would appear the film was banned for what it suggested, rather than what it depicted, and this makes it an interesting censorship case, worthy of closer examination. South Africa is not a country that takes kindly to censorship, given its abuse during Apartheid, but it is a somewhat more conservative society at large than, say, the United States or Europe. So just why was the film banned?

The Films and Productions Board (FPB), who issued the ban, presented the following in their letter to DIFF:

In terms of chapter 1 Section 1(e) of the Films and Productions Regulations, child pornography is defined as follows:"child pornorgaphy" includes any image , however created, or any description of a person, real or simulated, who is, or who is depicted, made to appear, look like, represented or described as being under the age of 18 years-(i) engaged in sexual conduct;(ii) participating in, or assisting another person to participate in, sexual conduct; or(iii) showing or describing the body, or parts of the body, of such a person in a manner or in circumstances which, within context, amounts to sexual exploitation, or in such a manner that it is capable of being for the purposes of sexual exploitation

When the first liaison with Nolitha occurs, both Sithole and the audience hypothetically don't know she is a minor. It is only in the next scene, when Nolitha first appears in Sithole's grade 9 class, wearing her school uniform, that her age is revealed (14-16). It was at this point that the FPB's classification committee deemed the film to have depicted child pornography, and stopped the classification process, i.e. turned the film off.

According to the classification committee, at 28 minutes and 16 seconds the classification process was stopped based on the the fact that the film contained child pornography. According to the Films and Publications Regulation 16(1) if the classification committee discovers child pornography during any classification process, the film, game or publication classification process shall be stopped.

South African law therefore requires that any film undergoing classification (rating) be stopped immediately if child pornography is observed. Consequently, the committee stopped the film after only 27 minutes, and therefore never saw the scene in the context of the full film, which would clearly have affected their interpretation of it.

By these letters of the law, the FPB is probably justified in their handling of the decision. Upon appeal, the lawyers for Of Good Report successfully argued that the film did not meet the Constitutional Court's definition of child pornography, which specifies it must be intended to stimulate sexual arousal in the target audience. In the context of the full film, the scene is clearly part of a cautionary tale, where "cautionary" is the greatest understatement since, say, "big bang." Interestingly, the FPB had previously lost a classification appeal on the same grounds (they banned Argentine film XXY), which raises the question why they persisted in using their own definition.

However, it must be said that even with the constitutional caveat, the contentious scene is shot to express genuine passion and arousal, and this is where one finds there are fifty shades of grey. Does that constitute intention to arouse the audience? It reminded me of Natalie Portman in The Professional, and even more so in the director's cut Leon, where her scenes were intended to be provocative and she was trying to be sexual for an older man. In the end, the filmmakers successfully, and I think accurately, argued that their intention was obviously not to arouse the audience, though the scene certainly expresses arousal. I think this subtle but substantial paradox is the crux of the matter; watching characters genuinely lust after each other naturally appeals to our empathy, but knowing that the lust is manipulative and morally reprehensible revolts our intellect.

So the obvious question then; why enact this ban without even watching the entire film? Because the law required that they stop the film if they found child pornography. Why does the law require that of them? Because it should - nobody should be watching that shit, ever. In my opinion, the bigger question is why did the South African classification board, and no other, find the film to have depicted child pornography.

This, I think, has less (though not nothing) to do with the subtle differences between the two definitions of child pornography, and more to do with the feelings of the viewers watching in the classification. Quite simply, they felt that it depicted child pornography, and once that feeling was acknowledged they had no choice but to shut the film down and deny it classification. But why did they feel it was child porn. If they hadn't felt that way, and indeed most viewers of the film have not, then they could have completed the film and at least made the call with more complete context. Instead, in South Africa and nowhere else, the film was banned. Why?

It is often impossible to write about South African film without writing about South Africa, and this is one of those instances. I go out of my way to try write from multiple and positive perspectives in an effort to dispel some of the cultural caricatures, but painful though it is to admit there are subjects that cannot be lit in a positive light. I fear that I will be tackling a number of such topics during this festival. South Africa is still very much defined by it's metamorphosis from Apartheid to "Rainbow Nation," and the country's filmmakers are in the vanguard of artists examining this ongoing process.

South Africa has the dubious distinction of - no, I'm sorry; dubious carries too mild a connotation - it has the fucking awful distinction of being one of the most sexually predatory and misogynistic societies in the world. South Africa has one of the highest HIV infection rates on the planet, and consumes about 25% of all antiretroviral drugs. Rape and sexual violence are major issues in their own right, but its the cultural acceptance and prevalence of "sugar daddies" that Of Good Report is especially focused on. Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi last year reported that at least 28% of South Africa's school girls are infected with HIV, versus just 4% of boys, clear evidence of older men commonly sleeping with younger girls. He added that 94,000 schoolgirls fell pregnant in 2011, that they know of, and 77,000 received abortions at public facilities. The reasons for this sad state of affairs are numerous, complex, and tragic, but if you're interested in learning more then this Medical Resource Council's brief is a good place to start. I will resist weighing in on this because it is not my area of expertise, but I will say this: things are improving.

The statistics, however, remain deeply disturbing - horrifying in fact - and perhaps the FPB can be forgiven for being a little trigger-happy with the ban button, given the circumstances. There is an appeal process for a reason, after all. But the most unfortunate outcome of this fiasco was the fact that the system created conflict between two sides who both sought to help stop sexual predation and violence. And, at least ostensibly, all over a technical difference in definitions.

Having watched the film twice, and having now a clearer understanding of both the censorship laws in South Africa and events surrounding the banning, I feel the ban happened for two reasons.

Firstly, South Africa's ill reputation and understandable sensitivity to the subject matter probably contributed to the hyper-sensitivity of the classification committee. Misogynism and sexual predation, especially on young girls, are national afflictions that flagrantly contradict the exemplar South Africa proudly embodies as the manifestation of Nelson Mandela's principles. They have become a touchstone issues in contemporary South Africa, and the collective efforts underway around the country to combat the scourge of gender ignorance leave little tolerance for it. I can't help but wonder if the public reception might not have been more critical of the film had it not first been banned, and elevated to censorship martyrdom.

Secondly, the film is that damn good. It got under my skin, as it got under the classification committee's skin, and lingers long after the final shot, which returns to the beginning having now revealed the ghastly truth about it. Great films have frequently pushed the boundaries of censorship, and it is no coincidence that this one did too - it is a great film!

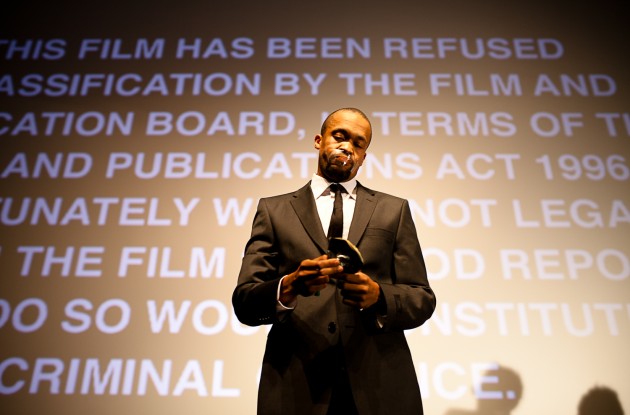

A year ago today, the festival's opening night went ahead, but instead of a film the stunned cast and audience were met by Qubeka standing silently on the stage, with mouth taped shut, and a message on the screen behind him:

This film has been refused classification by the FPB in terms of the FPB Act 1996. Unfortunately we may not screen the film Of Good Report as to do so would constitute a criminal offence.

Qubeka went on to rip up his South African ID document, symbolically rejecting his citizenship, while his wife, an ER doctor, gave an impassioned speech about the plight of young girls, who she treats for abuse and abortions on a daily basis. It was, bar none, the most dramatic opening night of any DIFF that I've ever heard of.

In the end, the ban was overruled in time to screen the film on the last day of the festival, though not in time for it to be in competition. The festival winner was eventually Durban Poison, based on the 1980's real life crime story of a couple who became known as South Africa's Bonnie and Clyde, Charmaine Phillips and Pieter Grundlingha - a worthy winner in its own right. Of Good Report went on to claim 13 African Movie Academy Awards nominations, winning 5 categories; picture, director, screenplay, lead actor (Magano), and new talent (Tshula).

Today, Qubeka is in London working on pre-production for his next feature, The Riders, a drama based on a novel by Tim Winton, which tells the story of a man searching across Europe for his missing wife, with his young daughter in tow.

Despite the furore over the thematic content of Of Good Report, Qubeka is on record as saying that he really just wanted to make a great serial killer origin story. Well, needless to say he achieved that end, and very much more.

Watch this film, and watch this name: Jahmil X.T. Qubeka.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.