Etrange 2013 Interview: Stephen Sayadian Is 'The Most Interesting Man In The World'

Magazines

I started out as a young kid as a satirist, doing parodies. I used to send things in to comic books, to Mad Magazine. I started out at Hustler because I was trying to get a job at the National Lampoon. I met Chris Miller, who was their lead fiction writer and who went on to write Animal House, and he saw my work. He said to me, “if you were really smart, you’d discover this men’s magazine Hustler. It’s just in its infancy, but the word is, this things gonna go somewhere. We going down the hill, and they’re on the uprise.” He put me in touch with another magazine editor who told me the same thing. Then I had heard about it twice, so I got in contact with them.

The period spanned in The People Vs. Larry Flynt, I was there practically from the time the film opens to when it ends. Crispin Glover kind of played out a combination of four or five of us. I was there for every bit of that, more than I could even tell you.

When I first got hired there, Larry was getting national advertising from the cigarette and liquor companies. But as Hustler started to push the boundaries, they started pressuring him to change to magazine. Larry being the guy that he is, said from here on out we weren’t going to accept advertising. We’d make our own ads selling our own line of sex products. Vibrators, dildos, love dolls. I was a 20 year old kid, and he told me, “I want you to use all your humor, and I don’t want the reader to know if its editorial content or advertising. Even I sell only one product, it’s more valuable than just a cartoon. Do what you want, but know that I’m going to treat it like editorial.”

So I ran with that. We had coupons and 800 numbers. People couldn’t get enough. I remember being told by the guy who ran the division, that at one time it was as much if not more profitable than the magazine itself.

Dressed to Kill

That image, when it was printed and released in the first time, had no tinting at all, it was straight black and white pointillism.

I had a partner for many years. He was the photographer and I was the conceptualist/art director. We would do many things. Sometimes you would create the image. The studios would send you just the title and a synopsis and you would go from there. What we specialized in was called the key art. We had nothing to do with topography or any of that. I did the conceptual image work and him the photography. Now, Dressed to Kill came and they had an idea that they wanted based on an image very similar to this. So we took the photo in color, but I painted everything on the set black and white. Then once we photographed the image, they took the negative and converted it to that look. It was a guy named Tom Martin who assigned that poster. He was an old colleague. Pretty much everyone who worked on this one were Hustler alumni.

The guy lurking in the door was my construction supervisor. He built the set and we had him stay around to be in the photo. We were such a small team we had to do everything ourselves. I put him in a jacket and a hat and said, “Now you’re done building. Now you’re gonna be the model.”

I’ll tell you a funny story. It was very important that we had these black stiletto heels in the photo and I could not find a pair anywhere. There was no CGI or Photoshop or anything then, so I went everywhere and could not find the right ones. But then I found a little bondage store on Hollywood Bd. So I go in and check it out, but the owner was really suspect of everyone who walked in. She eyed me suspiciously and I told her I needed Stiletto heels. Little did I realize, 99% of her customers were men. So she said, “I have Stiletto heels. They start in size 11.”

The model in the photo was a maybe a size 4 shoe. We had to stuff half the shoe to get it to stay on. Wilt Chamberlain could have fit into them!

We actually designed a second poster for this too. Sometimes when you would get a contract they would need a second image for the soundtrack, or a cash-in book. So we did another cover, and apparently, though I never got this confirmed, they commissioned other guys to do posters too. But Brian de Palma picked ours.

We never met that many directors. Very few of them ever came to our studio. John Carpenter did. He came for The Fog and Escape From New York.

We did many more, hundreds probably. This was one of the golden eras of one-sheets. They key art was very important.

Our specialty was the single image graphic. We mainly did horror films. It’s when video cassettes came in, they wanted to start having better box covers. We never looked at the film and we never used any of the people that were in it. They would just give us the title and we would recreate a single image, and we really honed our look.

Funnily enough, this Dressed to Kill set, and the one we used for Tobe Hooper’s Funhouse poster, both were used in my first film Nightdreams.

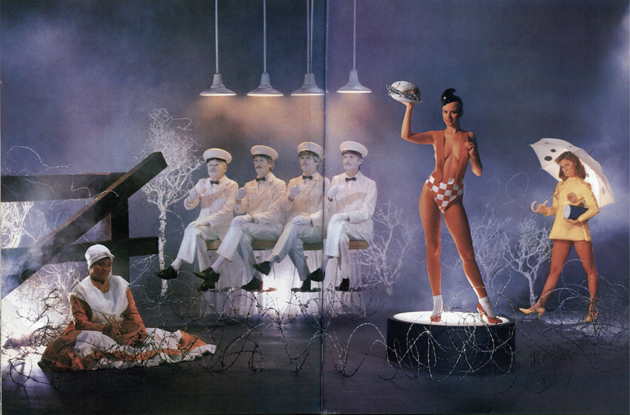

Nightdreams

I signed my first film as Rinse Dream.

The only reason I used a pseudonym on my porn films was because it was against the law not to. I was afraid I would get a knock on the door and be taken away in handcuffs. They would arrest you for prostitution by paying people to have sex. It was a felony. Not to mention the fact that I used to get paid in change.

I got $60,000 to make Nightdreams, and the entire film was paid in change. There used to be these peep shows everywhere. People would put quarters or dollars and they could see a show behind a glass wall, and it would go on for as long as they kept the money in. The people that financed that paid the budget of the film in coins. They didn’t want to convert it to bills. I made Nightdreams with $60,000 in quarters.

I sent out a PA – probably like the bass player of Wall of Voodoo, because my studio was at the heart of the Punk building of L.A. – and we bought like a hundred pairs of socks. Anyone who needed pay was handed a sock full of change.

I wish I had the forethought to document the making of any one of my films. People wouldn’t have any interest in seeing the films. The makings were so much crazier.

Everything I had ever done, in terms of filmmaking, my hands were always tied by the budget. The budget always came first. People always ask, how did you come up with this or that? And I always have the same terrible answer: I had no money; it was all I could do! I never shot a film on location. Not one location. And that was because you go where your strength is. I’m a good production designer, good art director, good enough for low budget, so you do that.

The original title was “I Know You’re Watching Me”. I though that was a great title for porn. I don’t anyone had ever addressed the person watching the film. “We know you’re looking at us…” But they rejected that title and then we called it Cracked – this was before the magazine - but they didn’t like that either. Somehow we settled on Nightdreams.

We did it as a series of six or seven vignettes; we just sat down and hashed out the concepts. We’ll go to heaven, we’ll go to hell, we’ll have one in the Wild West. It was supposed to be like an old vaudeville review.

We didn’t even have a crew. We had maybe five people. My partner Frank [Delia] was on camera, and there was one focus puller. There was the construction supervisor, who I grew up with and who could build any prop in the world, and there was me. And while Frank was shooting, I was just off camera range to the side, building the next set. It was an exhausting experience, but it felt like home movie.

Somebody asked the other day, Nightdreams, how do you explain? I told them, that’s what happens when you give a twenty-year-old kid with a little imagination a lot of nude women, a bucket of paint and some two by fours.

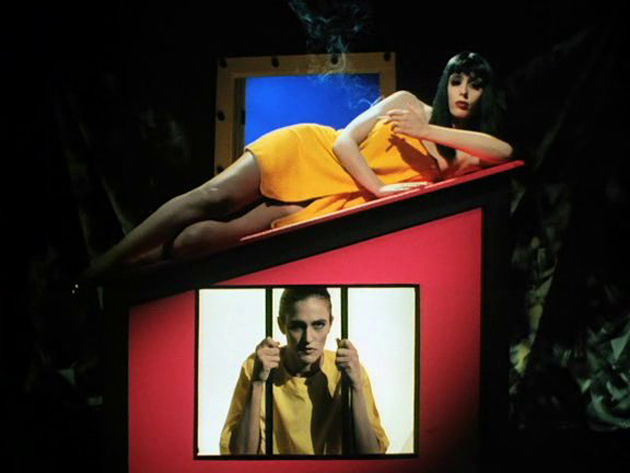

Café Flesh

There were twenty-two 35mm prints made of Café Flesh, which was a lot for a midnight movie. As far as I know, there is only one print remaining, and its owned by the Kinsey Institute at the University of Indiana. It’s always trying to be rented, still to this day. By the Kinsey people will not let it out, they treat it like its Citizen Kane god love ‘em. Maybe for the Kinsey Institute it is.

A year and a half ago, someone came there and pretended to be me to try to get the print. But the woman there was suspicious because the guy was half my age. She said, if you’re Stephen, how old were you when you made this? Four?

One night, in the middle of shooting Café Flesh, CNN talked the producers into letting a reporter come to the set. They wanted to see what it was like. It was right at the advent of VHS and home video, and they wanted to get behind the scenes and see what some dirty porno set looked like. I didn’t want to let them on, I was too busy working, It wasn’t easy doing all these set ups. But I didn’t have much of a choice, so the CNN guys came on set. They were jawdropped. They expected some dingy basement, and for everything else, this was a real film. They were in shock.

They asked, “What are you making here? Is this what pornography is becoming?” They were going to change the whole approach of their story. But someone said, no that’s not the way its done. It’s just this guy who’s crazy.

I came from hard porn, but was trying to inject an artistic film sensibility into it. But at the same time I was doing that, downtown in New York and in the L.A. scene, these people from the art world were putting porn into their images – people like Nick Zedd, Lydia Lunch, this transgression stuff – but if you look at that stuff today, I think we won out. I think our porn to art approach holds up much better.

And neither Nightdreams or Café Flesh were ever that successful as porn films. But they broke house records as midnight movies. We would replace Eraserhead and Pink Flamingos and tour the country. I thought, “my god, we’ve really got a genre here. We own this.”

But I think the art world was always too turned off by the porn, and the porn world too turned off by the art. Which if you think about it, is the perfect formula for failure.

Dr. Caligari

That period between 1919 -1938, it’s in my brain. It’s so much a part of who I am and what I do and how I look at things.

This guy came up to me who had made his money in porno, and he wanted to break out into low budget filmmaking. He wanted to make a Friday The 13th. I was always approached to do those kind of things. They always wanted me to make slasher films. I don’t know why, there was never any violence in my movies. I guess they saw I was really fast and efficient and could do lots of things. I’m a production designer and art director, which was the secret really. I would just build the set and go from there. But I never had any interest in those kinds of horror movies, it really wasn’t my bag. But this guy said, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is in the public domain. And I went, “Yeah I know. They remade it in 1962 and it was absolutely abysmal. If you have any sense of cinema history you’d know you’d be murdered from the start. Leave a masterpiece alone.”

And he said, “well, that’s the title I want, and I have $175,000.” So I took the job.

I set down rules. One, I certainly wasn’t going to film it in black and white. That would be pointless. Two, the whole storyline is irrelevant. Throw that out. But if I could take the spirit of the original, maybe we could have some fun with that.

Even in 1989, $175,000 was not a lot. We were shooting on 35mm, and it had to take us from preproduction to the final one-sheet.

The first thing I knew we needed to what shoot it all interior. I needed a bigger studio than mine. A friend of mine, Ray Manzarek, he was the keyboardist for The Doors, he owned a nice large studio on La Brea and Melrose. I had rented it before and we hit it off. He liked Café Flesh. So I asked him and he let me have the studio again for six weeks. That really helped.

I decided to conduct it like a theatre piece. I threw out any idea of realism at all. That’s where some of the expressionistic stuff came back in. I figured, why couldn’t I make one dreamscape, design it top to bottom, and then, in front of this one dreamscape just keep moving set pieces. If you see the film, that’s all I did. I basically had one set. Every reverse shot I just rolled in black. The camera was always static. I figured, instead of losing time with fancy camera moves, we could just put the actors on platforms and the sets on wheels. There are lots of shots that look like dollies or cranes but are just static. People see it and they can’t believe.

The film had to be color coordinated. That was one of the toughest parts. Pink and yellow were the main colors, so we had to dye all the costumes. There could be no realism. I designed a robotic body language for the actors, and that took some time to get them on board. Everything was done on set. There’s maybe one optical in the whole film. There was no money for them!

The editing only took about nine days. I didn’t have one shot in that film that wasn’t used. It was a cut to cut film. I storyboarded every shot, and then took the boards and made a comic book. I wish I still had that, but I gave it to some fan. I don’t keep anything.

The character of Gus, who’s a cannibal inmate of the asylum, has a line at one point about “a thousand points of light.” That was one of George H.W. Bush’s big campaign slogans during the 1988 election. Was that just a throwaway gag or did you have some political themes going on below the surface?

Well, I was born out the womb a radical leftist, but that’s neither here nor there with regards to the films.

That was just my writing partner Jerry Stahl who came up with that because he’s really funny guy. When that line played at a midnight theater, it got the biggest laugh in the entire movie. Brought down the house. Jerry went on to do some awful sitcoms…

…he wrote Bad Boys II.

And I forgave him for that. [Laughs]

I told him, “I forgive you for writing Bad Boys II, but you’ll never be forgiven for using your real name!”

One of the common stories around your films, goes “I had no idea what to expect, I was dragged to a midnight screening, or my friends put this on at a party, and it blew my mind. I was never able to find it again, but it burned a hole on my brain.” What was the first movie that burned a hole on yours?

It’s not something you would think. The movie that really knocked me out like no other film had was Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success. I must have been 13 or 14 and was just floored by every aspect of the film. Clifford Odets’ brilliant dialogue, James Wong Howe’s photography, the performances, everything.

Years later I had ended up starting a post-production company which really was just available for everything. We did commercials, rock videos, and we called it Falco Post, after Sidney Falco in Sweet Smell of Success. In the early 90’s I was invited to some cult things convention in Vegas. Russ Meyer was there and that kind of thing. And then who was standing in line signing autographs but Tony Curtis? And I knew had to talk to him. So I stood line just like everybody else, and when I get to him I start asking questions and we start hitting it off, talking all about the film. And we’re going on, and his manager says “you’ve already spent 20 minutes, move on”, to which Tony goes “give him 45 more!”

I told him, “the fact that you didn’t get nominated for Best Actor, and Burt Lancaster wasn’t nominated for Best Supporting Actor is one of the biggest mistakes in the history of cinema. But the fact Odets didn’t get nominated for his screenplay and that Mackendrick practically lost his career after making it, that’s a moral crime!”

And Tony said “I never took Hollywood seriously again after that.” I mean he did a lot of good movies, and he was even nominated the next year for The Defiant Ones, but Sweet Smell of Success was the best work he had ever done from the best script he ever read. And he owned that character. Lancaster too.

I went back and read the reviews from 1958. They mention [Walter] Winchell [whom Lancaster’s character JJ Hunsucker is clear reference to], they focus on all the wrong things. Mackendrick never got his hands on a real film again. Later he became the dean of CalArts. They called him Sandy, there. I went to meet him and was able to Xerox some of the original storyboard scriptnotes from the film. That’s a treasured possession.

It doesn’t have anything to do with my work, or my images, but it was the one that made me really aware of what a director did, how the camera moved. It left an indelible impression.

Past and Future

In 1995 I was told I had one year to live. I was diagnosed with a terminal disease.

Jerry and I had just finished a new script. It wasn’t X-rated but it was very provocative. It was called “Rapid Eye Movement”, and was by far the best thing we ever did. It was sort of the culmination of everything we had been doing together for eleven years.

I mean, besides the films, we had so many scripts and ideas and other projects, and we were sown at the hip for years. We finally thought we hit one out of the park, and we’re finally given a real budget, about a million to make it.

Then one day, I had a routine physical and they said you’ve got some problems. The doctor came back ninety minutes later and said I was in complete liver failure. He told me I had ten months to live. I was shocked, and went to get it confirmed at Cedar-Sinai. They lowered it from ten months to six.

Within a few weeks I was seriously ill, and stayed that way for the next ten years.

The irony was, I had advanced cirrhosis of the liver, and I’d never been drunk a day in my life. I didn’t drink. When I got the diagnosis, I wish I had.

I got a rare strain of hepatitis C, and the Center For Disease Control did this great story about how I caught it, but that’s a whole other story and we don’t have the time.

In 2008 I finally got a liver transplant. I took about a year to bounce back, and once I did I went and adapted Café Flesh as a stage musical. I did an Art Pepper show too. He was a jazz musician.

Since I stopped I don’t think anybody picked up the mantle. I mean, Lars von Trier, he’s superimposing heads [in his upcoming Nymphomaniac], why would you do that?

Just about a year ago I got the go-ahead for a new film. We just finished the script and getting it ready to shoot. I think it’s something dying to be released. Not because I’m doing it, but because nobody else is.

So I really can’t wait.

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada