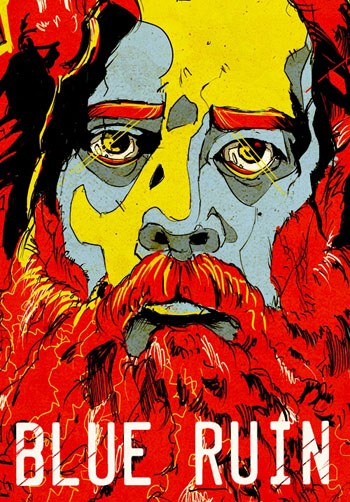

Etrange 2013 Interview: Jeremy Saulnier on BLUE RUIN

He spent this September hopping between film festivals, riding the waves of critical acclaim that started this past May when Blue Ruin screened as part the Director's Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival. The film was picked up for distribution both at home and abroad within hours of premiering.

If it all sounds too much a Cinderalla story it bears noting that the film really deserves it. From Cannes, Brian Clark wrote, "[we] doubt we'll see a more deft, thrilling genre film this year... it's rare that a genre-film takes the chances of this one and succeeds so resoundingly."

We caught up with him late one Etrange Festival night. The next day he was off to Toronto.

ScreenAnarchy: Who was the absolute worst corporate client?

Jeremy Saulnier: The funny thing is, and I'm not trying to be diplomatic, but I can't answer it because they all have blended together in my mind into one evil entity. They're all the same, every job is the same: interviews and B-roll.

The most disheartening thing about corporate videos is that you'll be in a room with twelve people, they're all your boss and no one will admit it. You ask, "who's in charge?" and they all look at each other in silence. And they're all above you, even if you have a strong desire to take charge.

I'm grateful to have a job, and they sustain me, but they force me out and I had to go pursue more creative things. It wears you down, and kind of forced me to make a movie again.

Did you ever try to sneak in any easter eggs, or something that delighted only you?

Oh I wish. Unfortunately I gave up a long time ago! [laughs]

There's no easter eggs, I just drink my ice coffee and make the day and go home.

But the truth is, it was this bizarre conflict of emotion when we got the acceptance email from Cannes. I was boarding a plane to go to Cleveland to shoot B-roll for IBM, and I was just scared to death, thinking, "What if this plane goes down? What if this corporate gig is gonna do me in?"

But it was also very empowering. The weight of the world was lifting, knowing what was in store. That was the most fun I ever had, shooting IBM B-roll in Cleveland knowing that in three days I'd go home and start preparing for Cannes.

When did you get the email? How soon before Cannes was it?

A big issue, one that I think led to an early acceptance for us is, they give very short notice for filmmakers. We did the math and originally just picked Cannes as an arbitrary deadline for a first cut, which we'd submit, then regroup, start post production and polish it off in time for a Sundance submission in 2014. But we quickly realized that we wouldn't actually be able to finish the film that way if we got into Cannes, so we said, lets inquire as to an acceptance or denial date, so we could alert other vendors. Because otherwise, we had all these friends, basically working in a basement, who were going to do sound mix over the course of eight to twelve weeks between real jobs.

So we asked them, when could we get a firm response date?

And they responded the next day, because the time difference and all. It was very funny. My editor, Julia Block luckily spoke French, so she had to translate for me. We got this invitation to 'envisage' and I said "What the fuck is that?! What's envisage mean??"

She said not to get our hopes too high, but they would take a look at the film, so let's just keep working. But that didn't answer the question! So I emailed again.

"Not trying to press, just need a firm Yes/No date. Just want to know the schedule."

And they wrote back another cryptic email, and we went back and forth a few times, and maybe they got sick of it, because finally they threw up their hands and said, "Fuck it, you're in." It was surreal.

We had originally submitted it to Sundance in November 2012. We got a warm response but the film was way, way too far from being finished for them to commit. [Producer] Anish [Savjani] and I sat down, said let's be realistic with our festival strategy, and came to the conclusion to use Cannes as a deadline, and really take our time finishing it before resubmitting for the Sundance 2014. We tried to be as clear headed as possible, and in the end we agreed, "this really isn't a Cannes film."

So it was really beyond all of our hopes and dreams.

Do you think the Cannes berth colored the film's reception?

I mean, I thought this film had something about it that could fill a void in the American scene, but I wasn't thinking about anything more than that.

I had confidence in it. I knew that once we finished up it would find a good premiere somewhere.

At the same time, I feel tremendous guilt. It's this fairy tale scenario where we got into Cannes, sold it an hour after the premiere, partly on merits, mostly because nothing else was around! It exceeded all expectations, and we're still catching our breaths.

Blue Ruin is almost an anatomy of a thriller. The lead starts with literally nothing, and has to put together his ramshackle revenge piece by piece, propelling himself forward through nothing but his own momentum. How much does the film's narrative - starting from scratch, getting in deeper and deeper as we go along -- reflect the actual process of making an independent film?

The narrative unfolded very naturally, but with a structure that was preexisting based on cobbled together freebie locations and resources that we had. I knew going into it where the finale would take place, where the main set pieces would happen and where the film would start. I had intimate knowledge of all those places, and more importantly, access to them for free.

There is simultaneously a highly practical method behind the movie, employing resources and being very conscious of budget, but owning that it allowed for a more emotional narrative approach as well. It wasn't an exercise or a challenge I put out for myself, just something I gravitated towards.

With Murder Party, we were shooting eight characters in a room. The amount of coverage, assuming we did two takes per person, was sixteen times through a damn scene before we could wrap. So I knew from the very beginning, no matter how this film took shape or what it ended up being, I wanted to have a single protagonist carving through space and time and narrative. I wanted to be able to fully realize each vignette, but also to get in and then get the hell out so we could continue.

In keeping with using known resources, you built the film around Macon Blair, someone you've worked with before.

He's my best friend. He's someone I trust as a person and love as a friend and admire as an actor. I've been making films with him since we were 11 years old. We both had these parallel careers, trying to break through in the industry. Our short film Crabwalk did well, and thought it might be our ticket to bigger and better things but it didn't really pan out that way. So I went back to advertising or camera work, he went back to auditioning. He got some decent parts in good movies, but never a lead role and I knew he could carry a film.

He's also a huge collaborator. Macon was on set for thirty days, but every other actor was on set for no more than five. Most of them worked two days. That way, we could get much higher quality talent, as far as professionals with experience, who would elevate both the film and Macon. They could be generous to us and not have to worry about accommodations, or being away from their families. Just come in for what amounted to a long weekend, do great work and head home.

The script, design and tenor of the film

were very much informed by direct opportunities you had in your life. If the one of the results of its success is the chance to make a film with a larger scope, do you think you'll continue with that same model?

Well, I think I used all my good locations on this movie. So I'll have to do some more research. It's going to be harder, and I'm looking forward to the challenge. The writing process on Blue Ruin was a new experience for me. I had to pay attention to the timeline, but otherwise it came together so simple and effortlessly. I had the benefit of pre-thought and visualization. The lesson learned is the more research you do, or location scouting or just investigating, the better.

I do feel that knowing space is key for my kind of filmmaking, though. We had a scene in a house, a seven-page action sequence that was very intricate as far as blocking and visuals go. We put forth great effort to find a location that would work for it and after a week and a half just gave up. Because I wrote it and designed for the house that I grew up in. The blocking and layout were already in place. And I could shoot it a lot easier. I mean, I knew every inch of it.

So we did a company move, two hours up the highway at great inconvenience, to shoot at my parent's house. That was against normal production logistics, and something I might not get to do again. But that's what made this different.

One last question. What was the last movie that you saw, not that inspired you, not that blew you away, but that made you kick yourself for not having made?

Oh that's easy. Three Kings.

Perfect movies, for me, blend genres. They don't try so hard to be one thing, they just are effortlessly everything. Three Kings is an hilarious comedy, a treasure hunt, a war movie, a buddy movie, it has so much in it. It's also an effective satire and that's rare.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.