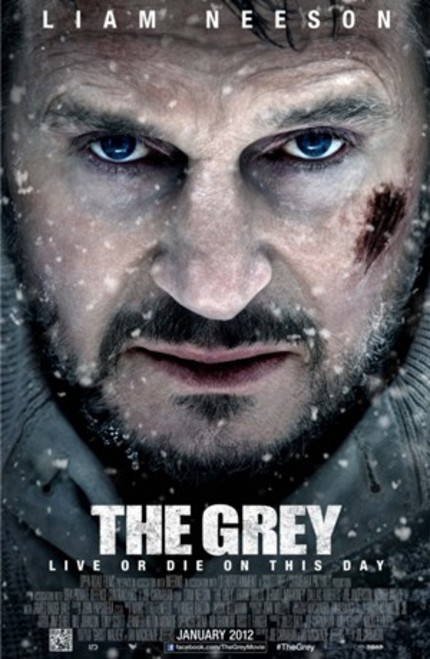

From Suicide to Salvation: THE GREY Explores the Darkest Region of a Man's Soul

"Let it slide over you ..."

(Note: Major spoilers for Joe Carnahan's The Grey abound in this feature article. Do not proceed unless you want to read about the ending.)

When we first meet Ottway (Liam Neeson), he is suicidal. He has been for some time, though we don't learn the specific, inciting factor until much, much later. Has he suffered from bouts of depression since childhood? Maybe. He talks about his father, his 'very Irish' father, in tones of reverence and respect and regret and resignation, tones that bespeak decades of mental reconciliation with the emotional and physical pains suffered as a child.

Ottway is not a young man. (Neeson is 59.) And he's come to a point in his life where he doesn't want to deal with the pain anymore. Through the course of the film, we learn vital pieces of information: his unhappy childhood, his knowledge about wolves and wilderness survival, his long relationship with a loving woman. Perhaps the woman ameliorated the pain to such an extent that the absence of her love ripped open the gaping, agonizing, festering wound that had been gnawing at his soul all along.

The pain has become too great, a burden that weighs him down, and he wants it to stop. The night before a return trip to Anchorage, Alaska, from the wilderness camp where he has served as part of the security detail to protect the workers from wolves and other dangerous predators in the wild, Ottway contemplates what awaits him, and decides that he cannot endure any more pain. It's not so much that he wants to die, or to stop living: he just wants the pain to end.

He heads out of the rowdy camp cantina, into the freezing cold, walks a short distance away, kneels down, gets out his rifle, places the barrel into his mouth, prepares to pull the trigger ...

(As the surest, least painful means of suicide, one source recommends shooting oneself in the stomach in the middle of the wilderness, as far away from other people as possible, reasoning that one's fingers might slip with a gun barrel in the mouth, leading to a protracted, painful experience with only part of your face blown off, while shooting oneself in the abdomen supposedly will cause the greatest blood loss in the least amount of time. Distance from others is important, since others might hear the gunshot and run to help out, thus possibly foiling the suicide attempt.)

Does Ottway truly want to commit suicide? He could have walked much further into the woods, away from the camp, and probably would not have been missed for hours. Is he hoping that someone will see him and dissuade him from his course?

He doesn't pull the trigger, placing him on an airplane that crashes in the middle of a wolf pack's territory. Snapping into survivor mode, he surveys the damage, assists the injured, and then fills the role of a secular priest for a dying man inside the plane. "Let it slide over you," he tells the man, after informing him plainly that he will die. It's a fact: the man is mortally injured and blood is pumping steadily out of him; there is no hope for a last-minute reprieve. Rather than pretend, Ottway tells him to accept; when death is inevitable, nothing else can be done.

Attacked by wolves, beset by the unforgiving wilderness, overtaken by time and circumstance, the survivors dwindle. As the final three men hike through the deep snow, hard-bitten Diaz (Frank Grillo) realizes he can't go on. His leg has been badly injured and the miles have taken their toll. He sees a good spot to sit down, next to a river, with a view of the gorgeous landscape. Hendrick (Dallas Roberts) argues with him, urging him to get up, but Ottway knows from personal experience that Diaz is not commiting suicide, though death is sure to come soon to the ex-convict. No, for Diaz, death is inevitable; nothing else can be done except make peace with it. He asks Ottway about death 'sliding over you,' and Ottway confirms his conviction. Diaz nods and is satisfied that he knows what awaits.

For his part, Hendrick fights to his last breath, even though Ottway doesn't know it. Running from the wolves, he's tumbled into a river and then swept downstream, his foot catching beneath rocks with his head underwater beneath a fallen tree. Ottway races to his rescue, but he can't move the tree. He yells at Hendrick to pull, to push, to hold his breath, to fight. Hendrick is fighting, but all the fight in the world can't help you when the elements are keeping you down.

Hendrick drowns, and Ottway is alone again. He rails against God, in one of the film's few awkward moments. None of the survivors has displayed any outward faith in a higher being, and Ottway doesn't have it either. He's angry, that's all; he waits for only a moment, as though expecting the Almighty to thunder from heaven at his beck and call, and then declares: "I'll do it myself."

In that moment, however, Ottway has achieved salvation. Perhaps not spiritual salvation, of the kind that would be acceptable to God (or to the gods of your personal beliefs), but his own emotional salvation. He could easily give up, like he thinks Hendrick did, or sit by the river and wait to die, like Diaz. Unlike Diaz, though, Ottway still has a measure of strength and health. The experience, harrowing as it has been, has given him the resolve to live, a desire to cope with the emotional pain he is still suffering.

Then he realizes that he has stumbled into the wolves' den, that all along the survivors were trudging directly into mortal danger instead of away from it. And that he has failed utterly and completely as a wilderness guide. And he knows he is going to die, slowly and painfully. And, when he dies, he can only hope that he will go to the same place as his beloved, who has preceded him into death.

Still, with his newly-affirmed resolve, the melancholy man will not go quietly. He is ready to deal with the pain; he will fight to the end. The Grey has tracked his path from suicide to salvation. Ottway is now prepared to go "into the fray" once more.

The Grey is now playing in U.S. theaters.