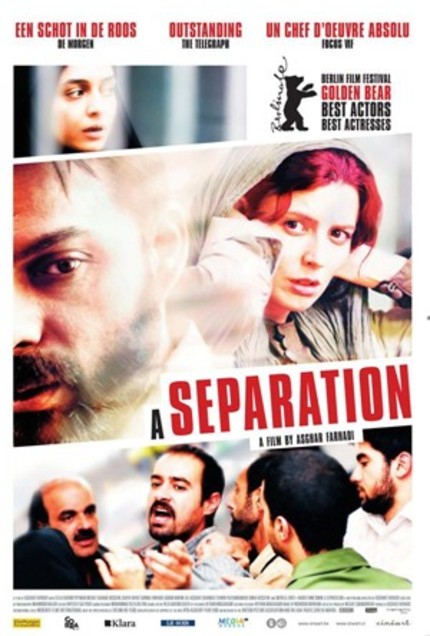

A SEPARATION review

Iranian cinema, probably one of the most artistically rich of today, has gone, in the last few years, hand in hand with the country's social and political situation. Often distinguished in European and North-American festivals, most Iranian films (those that manage to slip into the West, anyway) share an obvious tendency of indictment towards an archaic and chauvinistic regime, working in most cases as a cry for help and not necessarily clicking with those audiences who simply don't care. A Separation managed, in just a few months, to achieve more international projection than any film by Kiarostami or Jafar Pahani, of which the Golden Bear in Berlin and the nomination for the Golden Globes were just the beginning. With the start of the awards season it'll surely keep on collecting acclaim and appearing on end of the year top 10s, a route that will eventually end in the Oscars - whatever that's worth. All this success is due precisely to the fact that it's not just about Iran or Iranian society, but a much more complex and universal exploration of the human being as a whole, not just as a social and political animal.

Written and directed by Asghar Farhadi, a sort of master of suspense from Iran, A Separation is a family and social drama but mostly a moral one. The story may be about men and women, husbands and wives, parents and children, justice and religion in today's Iran, but since it grounds itself in such basic and relatable dualities, regardless of which continent one lives in, it manages to raise deeply relevant and universal questions about responsibility, gender, pride and the oh-so-elementary importance of telling the truth.

The film starts, unsurprisingly, with an attempt at separation by Simin (Leila Hatami) and her husband Nader (Peyman Moaadi), a middle-class couple from Tehran. Both sitting in front of a judge, Simin is the one who asks for the divorce, desperately wanting to leave the country and take their daughter Termeh (Sarina Farhadi) with her. This isn't a couple with severe problems, and it always feels like they're still very much in love, but Simin feels she has no choice when faced with Nader's intransigence, who refuses to abandon his father who suffers from Alzheimer's. On one side of the scale a generation's future, on the other one's dignity. Shot entirely in one continuous take, this scene, which goes on for quite a few minutes, is the perfect introduction; Farhadi shoots the couple faced front, putting the camera in the judge's position - and thus making ourselves the "judges". Once again, it's the perfect start for a film with a distinctive documentary-like quality, with Farhadi often putting us in that same position while showing the impartiality of someone who's merely observing and, well, documenting.

In any other film, the story would confine itself to the divorce, to the separation from the title and the way that would affect Termeh, making it a family-drama in the vein of Kramer vs. Kramer. But Farhadi, in A Separation's true stroke of genius, chooses to go elsewhere. Simin and Nader do separate, with Termeh deciding to stay with her father. Nader then hires Razieh (Sareh Bayat), a woman from a clearly lower social stratum, to take care of his father. In her first day she realizes she can't do the job because it entails undressing and washing him (a "sin", in her world-view), besides being pregnant and having to take her other young daughter to work. However, she keeps on doing it out of need for her husband Hodjat (Shahab Hosseini) is unemployed and keeps being thrown in jail for owing money.

It's from here onwards that the film shits completely and becomes something no one could possibly predict. By means of a tragic accident - of which it'd be absurd to speak - the action evolves into much darker territories, almost becoming a mystery or a thriller with court-room connotations and masquerading as a whodunnint in which someone has to be accountable not only by Justice but also by ourselves. With two clear sides - the rich couple and the poor one, no less - in constant conflict, we're thrown in the middle and forced to choose sides and/or decipher what happened. Farhadi's genius, a consequence of how he writes his characters, reflects in our inability to choose. We feel empathy for both couples, but also the opposite, eventually getting to a point where it becomes suffocating to watch the fight develop and their pride, stubbornness and religious fanaticism pull them in opposite directions and, at the same time, causing them to collide.

A Separation's two main themes are, in the end, responsibility and truth. Not family or divorce. Not that those don't matter - they do - but all the twists and turns, all the conflict that grows until ridiculous proportions are a direct consequence of the incompatibility of two stories that can't co-exist, two versions of the same event that can only have one explanation - one truth. The reason why we easily empathize with these people is the fact that they're completely human. And so we understand them, even when we hate them. We've all lied and hidden certain aspects of an untold truth, never measuring the actual consequences of that lie, and that doesn't make us automatically bad people. This is, I believe, the real core of A Separation, the way one single action can change everything. As for the actual separation, Farhadi may use it to trail a different path but he never forgets Simin and Nader, nor does he ignore what pulls them apart and, at the same time, brings them together. I find it quite ironic that the Kramer vs. Kramer of our time came out of Iran - and that it has little to do with divorce or child custody.