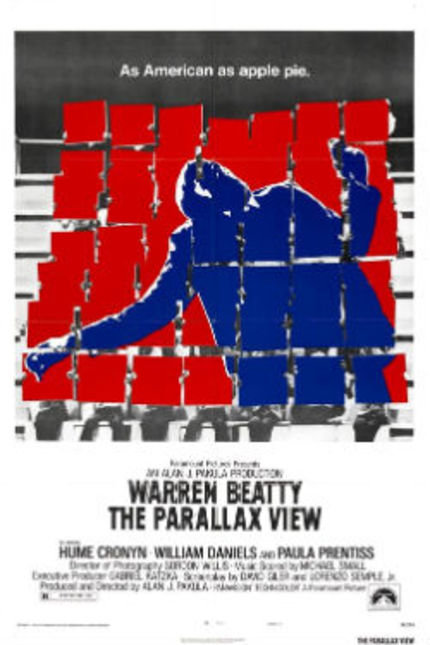

70s Rewind: THE PARALLAX VIEW

Pakula began as a producer, working with director Robert Mulligan, for 1957's Fear Strikes Out, a character drama starring Anthony Perkins as a baseball player, followed by To Kill a Mockingbird, Love with the Proper Stranger, Baby the Rain Must Fall, Inside Daisy Clover, Up the Down Staircase, and The Stalking Moon; most are respectable dramas (the last was an odd little Western) during a fairly bleak and dry period in American cinema.

Finally, Pakula got behind the camera as a director at the age of 41. His first film, The Sterile Cuckoo (1969), starred 22-year-old Liza Minelli; she was nominated for an Academy Award. His next effort, Klute (1971), featured Jane Fonda as a call girl, and netted her an Oscar. Both films were what you might call "respectable dramas," even as the subject matter in studio films was opening up, in response to the lifting of restrictions on adult content.

Klute marked the first collaboration between Pakula and director of photography Gordon Willis (President's Men would be their third), and the film reflects Willis' sensibilities, with pools of inky darkness waiting to envelop the characters. That same sensibility is much in evidence throughout The Parallax View, most notably in the meetings between Warren Beatty, as crusading reporter Joe Frady, and Hume Cronyn, as newspaper editor Bill Rintels.

At a certain point in the story, Frady and Rintels start to meet regularly in the latter's office late at night, after everyone else has left for the day. They represent "the good guys," to the extent that anyone in the story can be said to be fighting for truth, justice, and the American way, yet they're always half in shadow. They're never presented basking in the light; Rintels only appears indoors, and though Frady is out and about during the daytime, he's just as often squinting into the sun or disappearing into the shade. In one scene, his face gets splashed unceremoniously with mud.

There is no material difference in the way that Frady and Rintels, as the "heroes," are presented, versus how the bad guys are shown, sometimes clearly seen, but more often in the shadows. Only the eyewitnesses to an assassination, the innocent bystanders, consistently receive the fully lighted treatment.

Based on a 1970 novel by Loren Singer, with a screenplay credited to David Giler and Lorenzo Semple, Jr. (and, reportedly, an assist from an uncredited Robert Towne), The Parallax View first unfolds in Seattle, where a U.S. Senator is gunned down atop the Space Needle; his apparent assassin tumbles 600 feet to his death, and a congressional inquiry concludes that a lone gunman was responsible -- even though we saw a suspicious-looking waiter (Bill McKinney) slide a smoking gun back into his jacket immediately afterward and slip away, smiling.

Three years later, TV reporter Lee Carter (Paula Prentiss), one of the eyewitnesses, shows up on Frady's doorstep in Portland. Emotionally distraught, she says she fears for her life, that all of the witnesses are dying in accidents; she begs Frady for his help in tracking down political operative Austin Tucker (William Daniels), another eyewitness.

Up to that moment, The Parallax View feels very much like a thinly-veiled riff on one of the more enduring Kennedy conspiracy theories, what with the lone gunman and the witnesses mysteriously dying off. Gradually, though, it spins off onto its own, even more paranoid tangents.

Those tangents sometimes feel like 90 degree turns. Frady, for example, turns up in the small town of Salmontail in search of Tucker, only to be set upon by a volatile man named Red (Earl Hindman) who picks a fight because Frady orders milk at the bar. (And got the attention of the ladies.) Unspoken is the fact that it was 1974 and Frady had a full, long head of hair. Red questions his masculinity, we knew in 1974, not just because he dared to order an unmanly glass of milk, but because he was clearly a pretty boy with long hair and drew the eyes of the ladies. Long hair was common among young men in school, but still rebellious for adults.

The bar fight leads, shortly thereafter, to vehicular mayhem of a sort that doesn't feel organic to the story. This too, could be attributed to the times; car chases were almost de rigueur, which might explain its inclusion. Or it might be that the filmmakers were aiming for a dose of marketable entertainment that would present a conspiracy thriller as more mainstream than it was.

Between the novel's publication in 1970 and the film's theatrical release in June 1974, Watergate happened; President Nixon resigned two months later, and there's no doubt it colored the film's production and the way it was received by the public. Beatty, who would finally make the long-gestating Shampoo with Towne and director Hal Ashby the following year, plays the crusading journalist more like an undercover cop determined to expose political corruption, never seeming to follow any kind of recognizable morality other than his own. (We only see him sitting in front of a typewriter once; he never seems to take notes or ask questions like a newspaperman.) It's a stark contrast to the reporters who would play the central roles in All the President's Men.

It is a pleasure, however, to see Beatty give a performance unfettered by the distractions of an on-screen romance. He spars with Cronyn, who is very good, and interacts well with the supporting players (including Walter McGinn as one of the bad guys, Kenneth Mars in a rare dramatic role as an ex-FBI agent, and the uncredited Anthony Zerbe as a psychology professor). It's a star turn, but Beatty and Pakula don't allow his mannerisms, his diffident hesitations, to interfere with the characterization.

As a bonus, far beyond the nostalgia value (Pong! Paying for airline tickets on the plane, in cash!), there's a montage sequence that is still rather stunning, and the concluding sequence is a near-perfect masterpiece of construction, editing, framing, and pacing, with incredibly striking visual pay-offs. The less the film tries to tell, the better it is.

The Parallax View has fallen off the radar to a certain extent, so I'm grateful to Chris Vognar, Dallas Morning News critic, who recently hosted a rare theatrical presentation of the film as part of his Screening Room series, for sparking my interest in revisiting it.

Sadly, I missed the screening, but it inspired me to dig out my bare-bones 1999 Region 1 DVD edition. That edition is (more sadness!) evidently out of print. Gordon Willis' photography cries out for Blu-ray, and a few supplements would also be welcome. The Parallax View deserves to be in circulation.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.