Rome 2010: Studio Ghibli's KARIGURASHI NO ARRIETTY Review

The artists at Studio Ghibli are today accustomed to international acknowledgements. Since the Golden Bear awarded to Hayao Miyazaki in 2002 by the Berlin Film Festival, well deserved prizes and celebrative occasions have incessantly multiplied, sanctioning with formal honors a longstanding mastery in hand drawn animated cinema. The most recent token of appreciation came from the Rome Film Festival, which included in its 2010 program a rich retrospective dedicated to Ghibli features: a more than welcome event, that however might not stand today as groundbreaking as it would have less than ten years ago, when the circulation of these films in Western countries was decidedly scarcer. Actually, the Rome program did bring something new to the "conventional" way of celebrating Studio Ghibli, as aside renowned classics like Mononoke Hime (Princess Mononoke, 1997) or Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (Spirited Away, 2001) it included films that are today not often seen on the big screen, like Isao Takahata's Omohide Poroporo (Only Yesterday, 1991) and Yoshifumi Kondo's Mimi wo Sumaseba (Whisper of the Heart, 1995), and even rarer titles, among which the documentaries Yanagawa Horiwari Monogatari (The History of Yanagawa's Canals, Takahata 1985) and Otsuka Yasuo no Ugokasu Yorokobi (Yasuo Otsuka's Joy of Animating, Toshiro Uratani 2004) deserve to be mentioned.

But the greatest novelty that the Rome Festival hosted was the first screening outside Japan of Karigurashi no Arrietty (Arrietty the Borrower): a film which is new not just because of being the latest installment in the Ghibli repertoire, but because it is the first real sign that what the Studio has artistically achieved is not destined to remain property of aging and multi-awarded masters, but can pass on to younger generations of intelligent creators.

The path to Arrietty started in the summer of 2008, even if a project about making a film out of Mary Norton's cycle of novels The Borrowers was something Miyazaki and Takahata fancied well before the foundation of Studio Ghibli. Producer Toshio Suzuki reported that the idea of recuperating this old project came almost suddenly to Miyazaki, as he realized that its theme would have fit well into the present situation of financial crisis: borrowing things, in Miyazaki's simple and disarming logic, would just be more convenient than buying, nowadays. But, economy aside, the story of little people living on what men do not strictly need would have also been a perfect way to deal with another important crisis: the one concerning the lack of young directors at Ghibli. Since 1995, many efforts have been made to find someone capable of standing up to Miyazaki's and Takahata's quality standards. The premature death of expert animator Yoshifumi Kondo, a mere three years after his directorial debut with Whisper of the Heart, put at stake the process of succession. While Miyazaki kept on directing, notwithstanding his repeated announcements of retirement, no relevant new personality emerged. So, when Miyazaki proposed the idea of Arrietty and the little people, open to interesting visual developments while being rooted in the Ghibli tradition of adapting classics of the Western literature for children, Suzuki decided to entrust with direction an already accomplished Ghibli artist: 36-year-old animator Hiromasa Yonebayashi.

The development of the production was closely followed by Miyazaki, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Keiko Niwa, and it shows: the visual appearance of the film is perfectly responding to the Ghibli canon. The clear and detailed character design, the carefully crafted backgrounds and even some staples of Miyazaki's way of animating, like the slow and airy motion of the hair of a character, in response to a sudden emotion, are there. And sometimes, one can catch fleeting but clear allusions to notorious shots from films like Tonari no Totoro (My Neighbor Totoro, 1988) or Gake no ue no Ponyo (Ponyo, 2008).

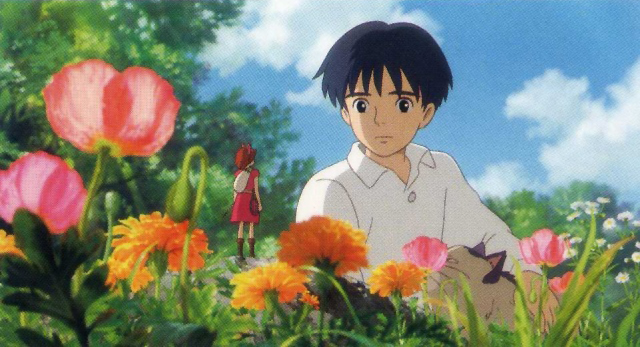

But these references and artistic debts do not prevent the film to find original ways of expression. They are, however, quite subtle. Apparently, this is just a gorgeously animated simple tale, about little people who live under the floor of a beautiful mansion in Koganei, Tokyo, surrounded by a vast garden. That was the house were the mother of Sho, a 12 year old boy, grew up, and it is now the place where Sho will stay, comforted just by the presence of the nosy housekeeper Haru and by his sometimes visiting aunt Sadako, while waiting for a difficult intervention of heart surgery. However, he will soon find out about the presence of the tiny guests of the house, who live by borrowing a few goods the humans do not need and by staying hidden. The lively 14 year old Arrietty, who had been looking forward for her entire life to accompany her beloved father Pod in a "borrowing" mission, gets seen by Sho at her first attempt. The incident worries Pod and his wife Homily, who understand that remaining in that house will now put their lives at risk. But at the same time, this is the beginning of a delicate relationship between Arrietty and Sho. The boy is gentle and quiet, but because of his sickness he has grown disillusioned and a bit cynical about life. In an important dialogue of the film, he directly tells Arrietty that the little people will eventually disappear forever, because of the mere fact that they are just three in a world populated by 6,7 billions of human beings. But thanks to the proud and strong-willed attitude of his friend, he will learn how even a fragile creature -like he himself is- can keep wanting to survive against all the odds. Yonebayashi's film appears as a new and soft-spoken embodiment of a theme really close to Miyazaki's sensibility: the right and duty to survive that living creatures have. In Karigurashi no Arrietty, no character says "ikiru" (survive) like Lana did, when she mentally shouted to Conan in a crucial underwater scene of Miyazaki's TV series Mirai Shonen Conan (Future Boy Conan, 1978), or as Ashitaka did when he pleaded to the fierce San in Princess Mononoke, a film whose promotional tag was precisely "ikiru"; or as princess Nausicaä did, when exhorting the people of a world slowly going towards an end, in the very last page of the 7 volume manga Miyazaki kept drawing for 12 years. However, the sense of Miyazaki's "ikiru" has surely been caught by Yonebayashi and it firmly pervades the story, even if it is expressed with quieter and less explicit manners.

It is because of these quiet "manners" that Karigurashi no Arrietty might seem, at a first glance, just a well crafted take on the Ghibli style, extremely respectful of the tradition it belongs to but devoid of Miyazaki's exuberant visual and narrative ideas. However, there is something that a second glance can reveal.

.

.It is something that emerges, for example, when Sho looks at the blades of grass in the garden of the house, towards the place where Arrietty is about to make her first appearance. To lead us from the world of Sho, the world of humans, to the little world of Arrietty, Yonebayashi just uses a smooth change of focus within the same shot. This is something extremely simple, from a cinematographic point of view: but it is not banal at all. The change of focus is not merely one of the many expedients that Yonebayashi could have used to bring us from Sho to Arrietty. It is exactly the only one that tells us about the connection between the two worlds, and about their coexistence, in a purely visual way, using the least possible resources to convey a maximum of meaning.

That change of focus is not an isolated occurrence in Karigurashi no Arrietty. It happens instead quite often, and it is accompanied by a series of other elegant ideas that contribute to a narration which goes on thanks to non-verbal features. For example, it is possible to remember how the director finds many effective settings that permit Arrietty and Sho to be harmonically present within the same scene, notwithstanding their very different dimensions. But, within these scenes, their reciprocal gazes meaningfully never meet at the same height until the last scene of the film. And, speaking of gazes, it is impressive how many mute interplays of glances Yonebayashi is able to orchestrate, by using the simple lines of the Ghibli character design to convey clear and refined emotive nuances. A couple of outstanding moments deserve to be mentioned: the silent humiliation of Arrietty while she has dinner with her parents after she was spotted by Sho and was told by her father to not tell her mother; or the terrifying calm glance of Sho when he witnesses the presence of Arrietty in his room, a glance that is counterpointed by the desperate attempts of Arrietty to find the severe but worried eyes of her father, in a slow choreography of subtle animations and silent replies that creates one of the best emotional contexts ever seen in a Ghibli film.

But it's not only a matter of visuals, as the one of Arrietty is not just a point of view, but also a point of hearing. Confirming a strong attitude towards non-verbal narration, Karigurashi no Arrietty has another point of excellence in sound design and sound editing. The towering shapes of armchairs, cupboards, fridges and sinks bring fear and amazement to Arrietty also because of the deep humming of electric engines working in the night, of the mysterious gurgling of the water inside invisible pipes, of the hidden crackles of the wood or of the overbearing and regular ticking of far away clocks. The impression of presence and the sense of scale that these sounds give to the action is impressive and fundamental to the way in which Yonebayashi constructs his miniaturized world. One may just regret that, within this artfully concocted audiovisual play, the music just does not find a right place. Cecile Corbel's score, in fact, shows too much that the composer is not a film musician but a folk singer: the musical cues are just instrumental versions of songs that sometimes play in the background, or that were featured in the Image Album CD of the film, without relevant changes in their structure and form. So, the relationship between the images and the music are often quite loose: meaningfully, the most impressive scenes of Karigurashi no Arrietty are the ones that do not feature music at all. Moreover, the music itself lacks the richness of inspiration and the authoritativeness of the styles of previous Ghibli composers like Joe Hisaishi or Yuji Nomi. Instead, it sticks with a generic "celtic" style, sometimes crossing the border of commercial pop music, that might be superficially appealing, but that does not offer more that suggestive sonorities and the cyclic repetition of melodies.

However, this is the only flaw that can bother the enjoyment of this work. In every other aspect, Karigurashi no Arrietty is a strong reassessment of the expressive power of hand-drawn animation. The moving and gentle narrative style of Yonebayashi might be less impressive than the one displayed in Miyazaki's wondrous worlds, or less cultured than the directorial touch of Isao Takahata. But it is, nonetheless, personal and effective. Yonebayashi's approach to animation seems moreover deeply aware of an important side of the Ghibli style, that a couple of years ago the animation director Kitaro Kosaka expressed with these words: «Ghibli films [...] show the world we passively live in from a whole new perspective. For example, we may have lost interest in blades of grass: however, I hope that someone, after having seen blades of grass in a Ghibli film, moving and transfigured by the detailed stylization of the drawings, will find a new pleasure in looking carefully when passing by a real meadow». What Yonebayashi accomplishes in Karigurashi no Arrietty is the artistic equivalent of a curious and passionate gaze at the world. It is enough to agree with something Miyazaki said, with relief, after the first screening of the film: «I felt a director appeared, at last».

Marco Bellano

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.