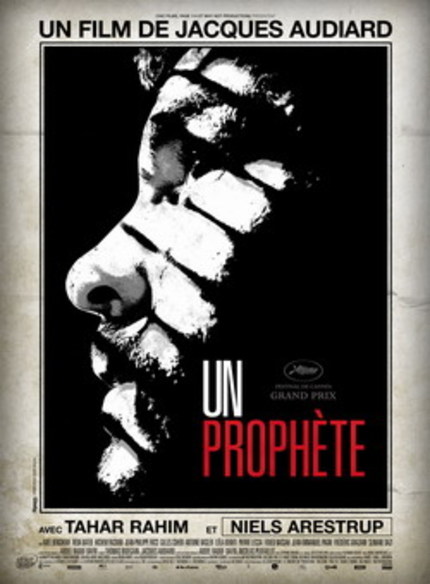

Sundance 2010: A PROPHET Review

[With the acclaimed drama A Prophet about to screen at Sundance, now seems a good time to revisit Michael Guillen's earlier review of the film, published at its Toronto screening.]

"Who you gonna get to do the dirty work when all the slaves are free?"--Joni Mitchell. In an environment of imprisonment and enslavement, such a question is fraught with peril.

Jacques Audiard's Un prophète (A Prophet) arrives in Toronto for its North American premiere after having won the Grand Prix at the 62nd Cannes Film Festival. As synopsized at Cannes: Condemned to six years in prison, Malik El Djebena cannot read nor write. Arriving at the jail entirely alone, he appears younger and more fragile than the other convicts. He is 19 years old. Cornered by the leader of the Corsican gang who rules the prison, he is given a number of "missions" to carry out, toughening him up and gaining the gang leader's confidence in the process. But Malik is brave and a fast learner, daring to secretly develop his own plans...

Although I immediately thought of the Biblical adage that a prophet knows no honor in his own country, Audiard disavows any Christian innuendo in the film's title other than that protagonist Malik--in a compelling, thoroughly convincing slow burn by newcomer Tahar Rahim--has acquired a gift for scrying the future after a (somewhat cryptic) near-death experience. At its simplest meaning, a prophet is one who sees the future. "Yes, the prophet is just a prophet!" Audiard advised Karin Badt at The Huffington Post, confirming the title's lack of religious subtext: "As for Jesus or Mohammed, I don't 'eat that kind of bread.' " Rather, Malik's future--in which he sees himself freed from the "protection" that enslaves him--hints at what SBS Film's Lisa Nesselson suggests is "a changing of the guard." Which, in itself, is an incisive yet hopeful critique of French classism and racism, wherein a better future can be imagined (or seen, if you will). Audiard has also stated that--though there is no Italian mafia in France--there is a mob, which happens to be Corsican. As Nesselson explains further, "by sheer virtue of numbers, the Arab and Muslim populations in French prisons are an increasing force to be reckoned with. Malik navigates between clans, each with their codes of respect and honor." At The Hollywood Reporter, Peter Brunette writes that Audiard "explores this basic tribal confrontation like a seasoned anthropologist." In effect, the pressures and prejudices of the social world outside the prison are inflected in the microcosm within the prison. "It's not all that different on the inside or the outside," Audiard explains.

How one manifests a prophetic sense of the future becomes one of the film's main narrative concerns, rendering a sense of destiny as achieved through self-constructed identity. As David Phelphs phrases it at The Auteurs: "A man's identity is the moves he makes." Despite petty crimes, Malik arrives at prison as something of a tabula rasa. Though Malik has been sentenced for juvenile indiscretions, he's not quite yet a true criminal, as much as he is a desperate young man. We are told virtually nothing about his past and we watch his character unfold and mature before our eyes as he negotiates his position within the prison hierarchy. At the L.A. Times, Kenneth Turan observes that A Prophet speaks to Audiard's long-standing interest in what he calls "self-education, the building of someone's character." In effect, Audiard aestheticizes the autodidact, the self-made man. As TIFF's program capsule synopsizes: "Audiard turns this premise into a probing psychological study of a disinherited, rootless young man, who initially makes choices based on the animal instinct for survival. When that need has been met, however, another set of motivations comes into play." At Moving Pictures Magazine, Eric Kohn notes the "undoubtedly tragic irony" in which Malik "gets forced into criminality by the very system intended to condemn it." Let alone that this criminality is his initiation into manhood.

Further energizing this philosophic and psychological enterprise, however, is Audiard's well-known penchant for elevating genre to artistic heights. Dispatching to Film Comment from Cannes, Amy Taubin observed: "Not surprisingly, some of the most pleasurable movies were by directors who fully embrace genre. ...A Prophet is elegantly structured, arresting in its detailing of a little-known subculture, filled with fascinating characters, and gripping beginning to end."

"What interests me about genre," Audiard explained to Kenneth Turan, "is that the public connects immediately with it, it has certain rules, certain codes the audience recognizes. I can use that to create something very big," an aim which--Turan notes--includes "creating icons, images for people who don't have images, the Arabs in France." Audiard has become the new master of the polar (French thriller), which he has intelligently infused with indirect socio-political commentary. Variety's Justin Chang describes Audiard's project as "solid, sinewy pulp fiction with strong arthouse prospects." At Screen, Jonathan Romney concurs that "A Prophet works both as hard-edged, painstaking detailed social realism and as a compelling genre entertainment." The blend makes for thoughtful, absorbing and ultimately entertaining filmmaking.

The film also plays with the tension between the literal and the phantasmagoric. The prison--with its "brutally restricted iron-and-cement palette" (Romney)--appears real; but, ends up being a completely constructed set because, of course, all the prisons in France were serving as prisons. Thus, even though the real is configured at its most naturalistic--with actual convicts cast to play themselves in prison scenes--it is likewise always held in question as a cinematic conceit. At Variety, Justin Chang finds Malik's education behind bars "improbable." One might even say romanticized. Even more intriguing is the ghostly presence of a man Malik is ordered to kill early in his prison stay. Throughout the six years of his sentence, this ghost hovers around Malik in his cell, his skin burning (as if registering that he is visiting from Hell); intimate evidence of the decisions Malik has had to make to become himself and to ready himself for his release back into the outside world. Surprisingly, the ghost is not a voice of conscience or guilt. He doesn't seem to judge Malik, despite the fact that Malik has taken his life and committed further atrocities. The audience finds itself in a similarly spectral position of non-judgment, satisfied by film's end with Malik's transformation towards the heart of his prophecy. He has become who he has seen himself to be.