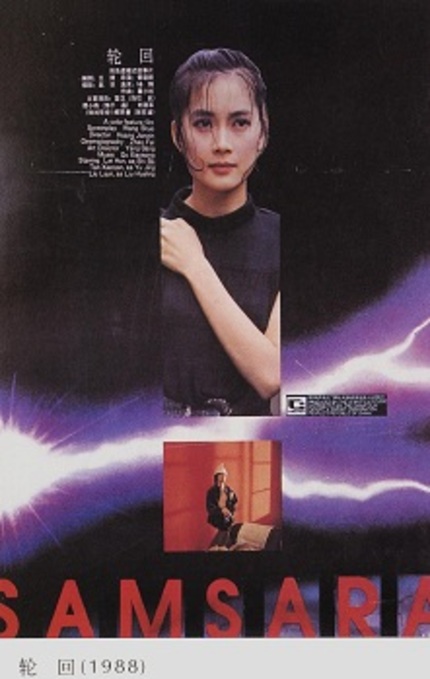

Huang Jianxin's SAMSARA (1988) review

(Though he's now (indirectly) best known in the West for The Founding of a Republic making the PRC very large sums of money, director Huang Jianxin remains one of Chinese cinema's best-kept secrets. For more than twenty years he's been making films documenting the vagaries of contemporary life on the mainland, the best of them richly detailed, funny, intelligent and thoughtful, but outside of a few festival appearances and academic citations he's gone largely unrecognised outside his domestic market. In the hope of pointing out he's done quite a bit more than co-direct one of the highest profile works of propaganda ever conceived, here's some of his work that deserves more attention.)

Samsara is the endless cycle of death and rebirth at the centre of many eastern religions - the idea of human existence as perpetual suffering, a slow, painful crawl towards enlightenment with no end in sight. Many belief systems see life as an illusion blocking the road to something better (or at least something else), and many filmmakers have made it out to be a purgatory of sorts.

In Samsara, Huang Jianxin's third feature from 1988, the narrative follows Shi Ba, the lead, an almost bohemian character in late eighties Shanghai. He has no job and no steady income beyond his inheritance and criminal connections; he drifts through life, rootless and aloof, (relatively) happy to exist outside society.

When he meets the pretty Yu Jing at a random dinner with friends, the two gradually become a couple, Shi Ba tentatively working his way through various conversational gambits, Yu Jing cautious but flattered by the attention. But those criminal connections result in a plot twist at the half way mark (and one shocking moment of violence) that leaves Shi Ba totally dependent on others. Now tied to a world he still can't identify with, he starts to slide into an emotional tailspin.

Compared to the rest of Huang's body of work Samsara starts out languid and dreamlike where his films, however slapdash, are typically focused - and the climax is bleak to the point of being fatalistic where he usually avoids passing judgement outright.

What seems like dry objective reasoning in The Black Cannon Incident or Gimme Kudos comes across as weary resignation here. The religious symbolism, such as it is, sees all Shi Ba's efforts to reject worldly temptations foiled time and again (his on-and-off relationship with Yu Jing, his criminal past). He finds comfort neither in bucking the system, nor in trying to live with it - the people Shi Ba meets who play by the rules don't seem to be any happier than he is.

Ordinarily Huang stops well short of suggesting China itself is irreparably flawed; he criticises the failings of bureaucracy and the naivete of the communist system, but he obviously loves his country and the people who live there and never resorts to suggesting they're living a lie. Gimme Kudos and The Marriage Certificate touched on the regime's problematic history but always seemed to suggest this history was something valuable in and of itself, that progress didn't mean sweeping the past under the rug.

Samsara makes little reference to history but there is a viciousness to the way it asks 'What did all this [the founding of the PRC] accomplish, exactly?' and it's an approach that doesn't entirely pay off, dramatically speaking. Misery needs a sure hand or a distinctive presentation to be really effective and Huang has neither enough material to work with here nor enough artistic flair three films in to elevate a two-hour thematic slog. Too much of Samsara feels as if it amounts to little more than 'life is hard, and likely to get much harder'.

At the same time there's enough talent involved the film is never less than watchable, sometimes very much so. It dates relatively well, some sequences or repeated motifs haunting for all the workmanlike visuals - Shi Ba wandering through a party early on, or carving an eerie silhouette into his newly painted apartment walls come the climax. The score feels weirdly saccharine and overbearing, but it's used sparingly enough.

It is undeniably powerful, too. The question is whether the inevitable conclusion - and decidedly bittersweet coda before the credits - could have been portrayed with more subtlety, a touch of grace. Huang has wrapped things up on a darker note since - one final line in Gimme Kudos is absolutely chilling, The Marriage Certificate is under no illusions its happy ending is some miracle panacea and the inter-office back-stabbing that goes on in Back to Back, Face to Face is far more genuinely shocking.

Samsara seems as if the director was overreaching in hindsight, that he subsequently acknowledged contemporary Chinese were capable of enjoying life under the Communist regime, having fun regardless of whether Buddhist doctrine saw it all as ultimately pointless. There's plenty for devoted fans of mainland arthouse cinema to love here, but even they may very likely find the film far too heavy going, especially when (like some Asian Michael Haneke) it seems to mock them for making the effort.