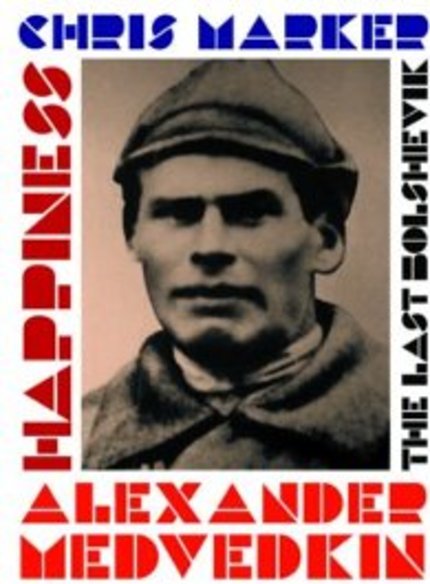

Review: Alexander Medvedkin's HAPPINESS and Chris Marker's THE LAST BOLSHEVIK

The dual release of Alexander Medvedkin's Happiness (1934, 64 minutes, black and white) and Chris Marker's The Last Bolshevik (1993, 2 x 60 minutes, black & white and color, separate English and French audio tracks) from Icarus Films will probably be the most comprehensive overview of the life and work of Alexander Medvedkin that will ever exist. Happiness is Medvedkin's key work and Marker's documentary provides the context necessary to understand the film's special place within the history of Russian cinema. The hours of material presented on these two DVDs is dense but anyone who spends the time to absorb what is presented will be rewarded with some of the most engaging cinema to appear anywhere in 2008.

Alexander Medvedkin served with the Red Cavalry beginning in 1917, and was eventually promoted to the rank of general and placed in charge of propaganda for the entire Soviet Army. Medvedkin gave up his rank to produce movies for soldiers, including the hygiene film Watch Your Health. Stalin's five-year plan began in 1928, and by the early 30s, Medvedkin was placed into service. He designed the Cine-Train - a film laboratory, an editing room, an animation stand and a projection room built into a passenger train. The goal was to travel the Soviet Union to instruct or assist in the kulkak's maintenance of the kolkhoz (collective farms) and industrial facilities. Medvedkin and a crew stopped the train in towns all over the Soviet Union, shot film, immediately processed the footage and screened the results to the towns people. Films like Journal Number 4, How Do You Live Comrade Miner?, and The Conveyor Belt presented cinematic propaganda as quickly as possible given the available means. The films presented best practices in harvesting or steel production to provide those in lagging collective forms and industries with side-by-side examples of how things were not supposed to operate. The animators created captions ("Comrades this can't go on") and the Cine-Train mascot: a disapproving animated camel that was paraded across the screen for the benefit of workers that failed to meet their goals. The aforementioned films all appear on Disc One of the Icarus DVD set.

Once the Cine-Train came to a halt, Medvedkin made the 1934 tragic-comedy Happiness. In his travels throughout the Ukraine, Medvedkin came across a kulkak whose expectations did not conform with life in the collective farm. This peasant's plight inspired the film's story of Khmyr, a man whose life is squeezed from all sides by the monarchy, the state and the church. Khmyr has simple dreams of happiness but like his ancestors, basic comforts elude him. Khmyr attempts to commit suicide but the aristocrats, the army (all of whom wear the same ghoulish grinning mask), and the church descend on him. "Who gave you the right to an improvised death?" they ask. Khmyr is eventually shown the way to happiness by his wife, who embraces the life of the farm by mastering the machines and techniques necessary to make the system work. The film's knowing portrayal of peasant life, its brutal representation of the Tsarists and the Russian Orthodox Church, and the flashes of eroticism can be found in works like Alexander Dohvenko's Earth and what exists of Eisenstein's Behzin Meadow. The surreal mix of gallows humor and Buster Keaton-style physical comedy, however, seems unique amongst works of this era.

Chris Marker's The Last Bolshevik is a biographical ode to Alexander Medvedkin in the form of a series of visual letters. As typical of Marker's style, the film is a dense barrage of interviews, film footage, and photographic montage guided by an omnipotent narration. The Last Bolshevik is fairly essential in understanding both Happiness and the Medvedkin's stature in early Soviet cinema. Medvedkin was a contemporary of Dovzhenko, Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov (Man With A Camera). Like his cohorts, he was an artist in the service of the state whose vision and temperament did not always conform to the expectations for totalitarian art. Happiness was boycotted by the Soviet press and bureaucrats stormed the set of his next production because of his defense of Eisenstein's controversial Bezhin Meadow, which was banned by the Soviets in March of 1937. Medvedkin never met with physical harm (cf. Isaac Babel) and continued to make films such as the Busby Berkely-esque New Moscow, Miracle Worker, and Lullaby but never fully satisfied the bureaucrats that his work held to the standard of Stalinist art.

Medvedkin continued to work well into World War II. After the Soviet-Russian pact fell apart, Along with Vertoz and others, he participated in the Soviet propaganda campaign against the Germans. Medvedkin went to the Russian front lines, documenting events such as the recapture of Minsk in real-time. Ever the innovator, Medvedkin designed a filming device for soldiers: a 16mm camera mounted on a rifle stock. Clusters of soldiers were sent to the edge of the war front. A single soldier hid and filmed the others as they ambushed and killed German soldiers. In this one device, one sees the ultimate representation of Medvedkin's art: the camera as a weapon. In an extensive interview about the Cine-Train captured in Marker's 1971 film The Train Rolls On, which is excerpted on Disc Two, Medvedkin directly invoked the metaphor:

"The cinema wasn't only a means of entertainment, a way of stirring artistic emotions. It was also a powerful weapon which could rebuild factories and not only factories: it could help rebuild the world. Film, in the hands of the people was a fantastic weapon."

The great irony in this statement is obvious. As Medvedkin's Cine-Train spread best practices across the kolkhozs in the 1930s, the Stalinists were implementing forced collectivization and creating the Great Famine that killed thousands of these same people. Then, as the Soviets entered World War II, Medvedkin soldiered on in creating propaganda, however nonconforming, for the very state that imprisoned and killed his colleagues. Thus, perhaps the most significant lesson presented by this DVD set is as follows: if the camera really is a weapon, one should always be wary of the direction in which the weapon points.