Morelia 2025 Interview: IT WOULD BE NIGHT IN CARACAS Directors Mariana Rondón and Marité Ugas on Shooting Their Political Thriller in Secret

Set in 2017, It Would Be Night in Caracas depicts political upheaval through the eyes of a Venezuelan writer desperate to flee the country. As the city collapses around her, she is threatened by revolutionaries, the police, and paramilitary operatives.

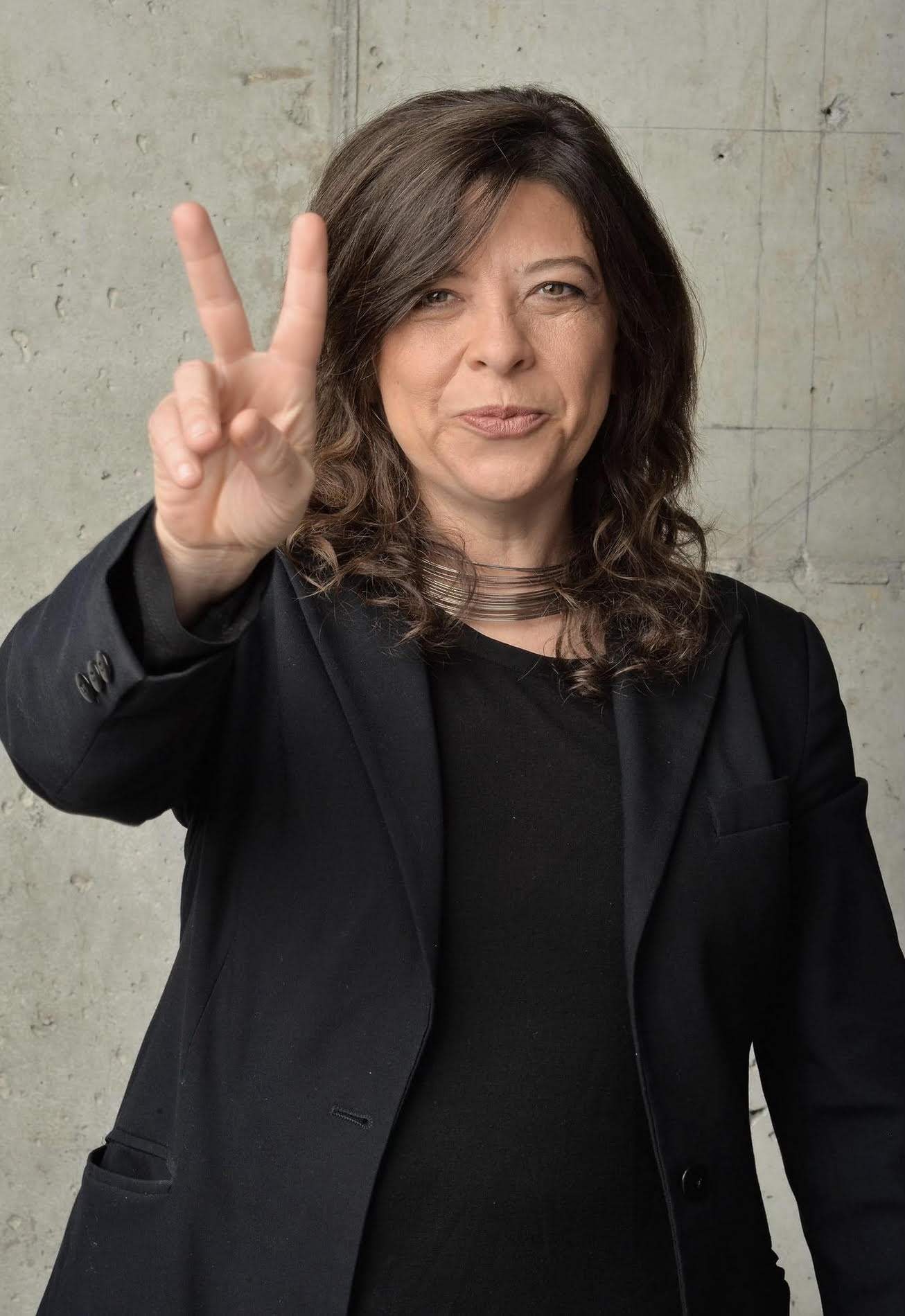

Based on a novel by Karina Sainz Borgo, the film was co-directed by longtime filmmaking partners Mariana Rondón and Marité Ugas.

Through their Sudaca Films, the two have worked together on a half-dozen films, including Bad Hair (2013) and last year's Zafari. During the Covid pandemic, they were invited to adapt Borgo's novel by the production company Redrum.

ScreenAnarchy: How did you come to this project?

Marité Ugas: The novel came out in 2019. It was an immediate bestseller and translated into several languages. No other book described what was going on in the same real and very well-written way. Then came the pandemic, during which we were working on our own projects.

In the middle of the pandemic, Edgar Ramírez and the Redrum producers in Mexico wrote asking if we would be interested in adapting the book. We were in the middle of writing the script when they invited us to co-direct the film. At that point, Ramírez was going to produce and act. Natalia Reyes was attached to star.

While we were working on the project, our film Zafari screened at the San Sebastián International Film Festival in 2024. By that time we were prepping Caracas, which we shot in the beginning of 2024. We finished post-production on that just in time for the Venice International Film Festival.

What was it like co-directing?

MU: When we started out, we co-directed our first film. From then on, we agreed not to co-direct anymore. [Ugas and Mariana Rondón burst into laughter.]

We fought too much, so we decided we were going to switch roles. When one would direct, the other would handle the production details. When this offer came, and we both decided to direct, we were a little bit suspicious of how it would work. But we found our way, and we are very happy with the experience.

Is this a much bigger film than your other projects?

MU: Zafari was pretty big, I mean we had seven co-production companies. It was an ambitious film. With this one, the delicious part was that we didn't have to manage anything about the production. The team in Mexico had a lot of empathy for our previous projects. We're picky about the production schedule, about establishing enough time for mise-en-scène, because we believe that's the best way to stay on top of the shooting process. They respected our way of working.

We scheduled a lot of time for rehearsals. We worked with the actors for about a month while we were scouting and prepping.

The migration out of Venezuela has been so severe that a lot of Venezuelan actors were already living in Mexico. We had top class actors who agreed to small roles, three-minute roles, because they believed in the project.

Edgar was there for the rehearsals. He's the one who got the book, and who looked for the production house. He's been involved since the very beginning.

And Natalia was with us right from the start. She was in love with a film Mariana directed called Bad Hair and wanted to work with us. We knew her work from Birds of Passage / Pájaros de verano, which screened at Cannes in 2018.

You shot in Mexico, largely in secret because of the nature of the story?

MU: We would never have received permission to shoot in Venezuela. We found locations in Mexico to represent Caracas.

What are the political conditions like in Venezuela right now?

MU: Very complicated. Maduro didn't accept the results of the last election. [Nicolás Maduro has acted as president since 2013.] That means the government is in power without support from the people. Anyone who opposes the government is jailed. They used to be "disappeared," now they are jailed. At least we know where they are.

At first, anyone who protested the government had their passports confiscated. Now they are going directly to jail. And because of the brutality of police and military responses to demonstrations, people can't protest in the streets anymore. You can be shot in the streets.

Mariana and I live in Lima now. I'm from Peru originally, she's from Venezuela. Frankly, it's not very comfortable, because some eight million people have left the country and spread out over South America. The xenophobia is everywhere.

Are you in any personal danger?

MU: No. I mean, we knew when we did this that troubles were going to come with the film.

How long was the shoot?

MU: We had four weeks in the studio, then three weeks for all the scenes in the streets. The demonstrations, the scene in the cemetery, all of that.

I was amazed by the scenes in the streets. You captured the tension and chaos, the danger and terror of a city out of control. I'm not sure how you got that footage.

MU: We used stock footage from AP and Reuters, which we would combine with our own shooting. We worked very closely with production designer Ezra Buenrostro. He sent scouts to Caracas to get a better understanding of the terrain.

It's a huge modern city from the fifties, with all these bypasses and elevated highways. It was difficult to find something similar in Mexico, especially since Mexico has all these hanging telephone wires and electricity lines.

Well, that explains the look but not your actual content. You have one long take where Natalia's character is trapped in the middle of a violent demonstration. It's an astonishing shot.

MU: Mariana is a great visual artist. She designed a storyboard for that sequence which we went over closely with our DP Juan Pablo Ramírez. He shot La Cocina / The Kitchen before our film, so he had some experience with this kind of material. Although he had only worked in studios, not in the streets, so it was kind of a brand new experiment for all of us.

We decided to use a whole day of shooting just to rehearse the shot. That was a very nerve-wracking choice because you know how important each production day is.

We started out with Juan Pablo shooting Natalia, with us behind him. Then we added the details. First the kids run towards her, then the policemen, then the army. It was the first time we worked with stunt artists. When they asked us, could they do this or that, we said, "No, we don't need the violence."

Then we saw this bit they did attacking a guy, and we were like, "More, more!" There was a lot of adrenaline.

Mariana Rondón: We didn't invent any of the violence. We only reproduced what actually happened.

MU: Every incident represents exactly what we've seen, either in newsreel footage or what we've seen in person.

We did three takes, and I think the second is the one we ended up using.

You also use a very specific, richly detailed sound design.

We've worked with our sound designer, Lena Esquenazi, and composer Camilo Froideval for twenty years. So we really know what we want. In the studio we knew what sound would go in what corner, how to do the motorcycles, everything. That's how you establish the geography for viewers. We also had a wonderful editor from Chile, Soledad Salfate.

Do you have a distributor for North America?

MU: We hope to. Right now we're getting ready for the São Paulo Film Festival in December.

The film recently screened at the Morelia International Film Festival.