Rotterdam 2025 Reviews: THE TREE OF AUTHENTICITY And THE GREAT HISTORY OF WESTERN PHILOSOPHY, From Congo And Mexico

Looking at two experimental films which use their forms as messages.

The IFFR Tiger Competition has a long tradition of narrative and also more experimental films. The following two films belong to the latter category. The Congolese film The Tree of Authenticity (L'Arbre de l'authenticité) from 2025 and the Mexican The Great History of Western Philosophy. Both films had their world premiere at the festival and both are also kaleidoscopic films, in which the story is formed by a series of stories and anecdotes, which partly overlap in image and sound.

The Tree of Authenticity

L'Arbre de l'Authenticité, by Congolese artist and filmmaker Sammy Baloji, is is a factual, three-part essay to present the findings and experiences of various researchers in Congo. Where the story partly takes place in the past, the makers use spoken voice-over texts against carefully photographed images of contemporary Congo. Sometimes the images and spoken texts form a counterpoint, but mostly they enter into a new kind of connection. They are helped by the static camerawork, occasionally alternated with equally concise drone shots - the only times the camera moves - that provide an overview of the photographed landscape. A colonial settlement in decay, a rainforest, a single well-maintained institute building and in the background the Congo River. The river that is not for nothing consistently described as 'The Mighty', in reports about explorers such as Henri Morton Stanley.

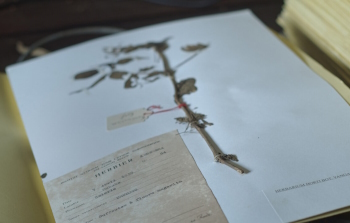

Around 2012, the Belgian biologist Hufkens wanted to install a carbon measuring tower at the site of Yangambi in the Congo Basin as part of his scientific research. A tower to register fluctuations in carbon and CO2 at different heights above the ground surface with the ultimate goal of measuring the carbon storage capacity of the second largest tropical rainforest. This measuring tower is a recurring visual motif in the film. Another visual motif is close-ups of the archive where Hufkens rediscovered a three-quarter century old biological archive in Yangambi. The archive contained precise observations of trees and their growth from 1937 onwards. Together with weather observations, the archive can provide an image of the development of the rainforest and its influence on the climate. The first part of the film zooms in on all this factual data.

Around 2012, the Belgian biologist Hufkens wanted to install a carbon measuring tower at the site of Yangambi in the Congo Basin as part of his scientific research. A tower to register fluctuations in carbon and CO2 at different heights above the ground surface with the ultimate goal of measuring the carbon storage capacity of the second largest tropical rainforest. This measuring tower is a recurring visual motif in the film. Another visual motif is close-ups of the archive where Hufkens rediscovered a three-quarter century old biological archive in Yangambi. The archive contained precise observations of trees and their growth from 1937 onwards. Together with weather observations, the archive can provide an image of the development of the rainforest and its influence on the climate. The first part of the film zooms in on all this factual data.

The second part of the film is much more narrative, thanks to the use of the diaries of Paul Panda

Farnana (1888 -1930). Farnana, born in Congo, went to Belgium at the age of 12 and was trained there as an agricultural engineer. In 1909 he returned to his native country as a third-class agricultural engineer. Around 1914 he lived in Belgium again and fought on the side of the Belgian army against the invading Germans, was taken prisoner of war shortly afterwards and was only released after the end of the war. Farnana, then in his thirties, became a leading critic of abuses in the Belgian colonial project on his native soil. From this broad perspective, his diary entries in voice-over provide a fascinating picture of Belgium and Congo around the First World War.

The third part of the film is also structured around diary entries, this time from the Belgian administrator in Congo Abiron Beirnaert (1903 -1941). Beirnaert tells a fascinating story, and at the same time in a mixture of colonial alienation, about his sometimes adventurous Congolese experiences. Like the time he accidentally hit a baby elephant during a long unforeseen night drive and was chased by two raging adult elephants.

The structure of the film in its three separate parts thus forms a parallel with the way in which

scientific research is organised in the field. It is also no surprise that the writer-researcher David van Reybrouck of the book 'Congo' collaborated on the script. The images of Sammy Baloji and

cameraman Franck Moka are an observant and meditative counterpoint. Apart from that, the strength of Baloji and his team lies mainly in the way in which their film makes life in the Congo Basin, now and in the colonial past, tangible.

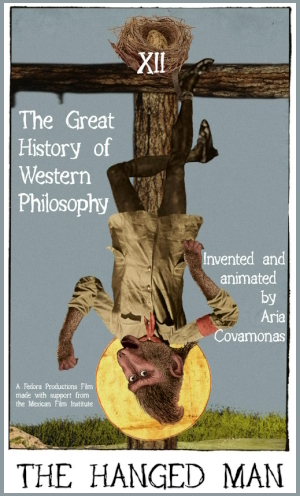

The Great History of Western Philosophy

Where L'Arbre de l'Authenticité is methodical and documentary-driven, the Dadaist animation The Great History of Western Philosophy by by Mexican filmmaker Aria Covamonas uses an opposite approach. One where everything is possible. The monk Xuanzang from the classic Chinese novel ‘Journey to the West’ is central. Aria Covamonas identifies the monk who tells the story with himself as a ‘cosmic animator’. This main character, as in the novel, is accompanied by a quartet of fantastic helpers. The Monkey King who has a monkey head on a human body, Zhu Baji with a pig’s head on a human body, the demon Sha Wujing and the Dragon Prince, who sometimes changes into a horse, which is useful for transportation.

Where L'Arbre de l'Authenticité is methodical and documentary-driven, the Dadaist animation The Great History of Western Philosophy by by Mexican filmmaker Aria Covamonas uses an opposite approach. One where everything is possible. The monk Xuanzang from the classic Chinese novel ‘Journey to the West’ is central. Aria Covamonas identifies the monk who tells the story with himself as a ‘cosmic animator’. This main character, as in the novel, is accompanied by a quartet of fantastic helpers. The Monkey King who has a monkey head on a human body, Zhu Baji with a pig’s head on a human body, the demon Sha Wujing and the Dragon Prince, who sometimes changes into a horse, which is useful for transportation.

In this surreal setting, the cosmic animator is commissioned by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, under the watchful eye of chairman Mao Zedong, to make a film about Western philosophy. From Plato to Nietzsche. And while the premise of the journey and the assignment retain a certain internal logic in which Mao and the animator are constantly at loggerheads, it unfolds on screen as a magnificent orgy of animated images. It makes the film essentially a large collage of moving paintings, each telling its own fragment of this larger Dadaist story. In it, Mao's strict attempts to supervise the entire enterprise seem doomed to failure. Before we know the outcome, the heroes, including Mao and the cosmic animator himself, must still navigate a sea of often comic conflicts. Anyone who claims to be able to follow the story in all its sidetracks has probably overlooked the images, which is a pity, because they are precisely those that are astonishing in their abundance in this ultimately inimitable work by Aria Covamonas.

Rewarding challenges

In both films, the story is in differing degrees subordinate to the form, which is determined by the

content itself. In L'Arbre de l'Authenticité this form is shaped by scientific research and the haunting beauty of decay and the exquisite detail of the rainforest. The Great History of Western Philosophy is driven by a fascination with the potential of animation to use image and sound to give the absurdity of reality perceived by the maker a meaning rooted in the form.

In a sense, both films are excessive, one in its meticulous methodology, the other in its wild but

consistently composed form. Both films are a challenge to the viewer addicted to narrative cinema. An invitation to surrender to a different kind of cinematic experience that is certainly worth the effort.