THE EXCHANGE Interview: Dan Mazer on His Anti-Racism Comedy

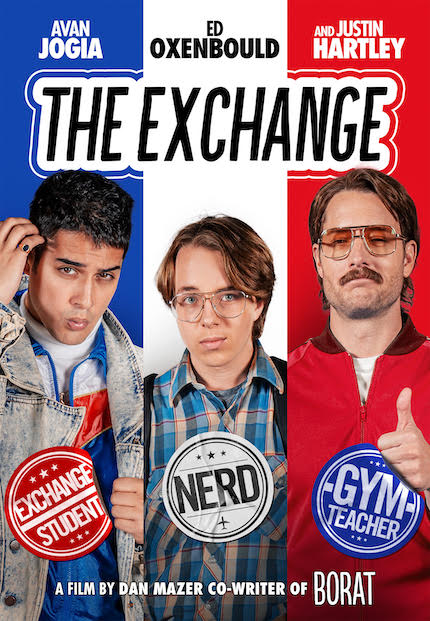

The Exchange takes place in the fictional small town of Hobart, in Ontario, Canada, during an economic recession in 1986. In snowy Hobart, "home of the white squirrel," teenager Tim Long (Ed Oxenbould) feels alone and misunderstood. Nobody else seems to be interested in literature, the music of bands like The Smiths, or French cinema (his favorite film is Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le cercle rouge).

Tim applies for an exchange program that brings French students to Canada, with the desire for a friendship. The boy imagines spending time with someone as cultured as him, however, when he finally meets the visitor, his expectations aren’t met at all.

The film's co-star is Parisian Stéphane (Avan Jogia), a charismatic and lively young man whose main interests are limited to sex, porn, football and hip hop. It doesn’t take long for him to become popular with Hobart’s residents, much to Tim's annoyance.

The Exchange is a very funny comedy about the development of an unlikely friendship. It also functions as a coming-of-age story, full of learning for its protagonist and with romance included: Jayli Wolf plays Brenda, an indigenous girl who evidently likes Tim.

The film sends a clear message against racism and xenophobia. Hobart is the reflection of small towns in Canada or the United States, with a predominantly white population, where prejudice and racial discrimination underlie. "You got to finally see the real Hobart," Brenda says at one point to Stéphane, son of immigrants.

I talked about these themes with Dan Mazer, who directed The Exchange based on a very personal script by Tim Long (renowned writer of The Simpsons). Mazer, it should be noted, has collaborated consistently with Sacha Baron Cohen for more than 20 years; he also directed I Give It a Year – the irreverent romantic comedy about a doomed marriage – and Dirty Grandpa, where Robert De Niro is a wild and horny old man.

ScreenAnarchy: THE EXCHANGE is a personal story for Tim Long. How was the creative process between you two?

Dan Mazer: Probably the fact that we were both writers gave him safety. We bonded over the fact that we had quite a similar background, albeit he was in the middle of Canada and I was in the middle of England. I identified with what he wrote, because I grew up in a small town and was similarly seen as an odd kid, but wanting to be creative. It’s a really funny script, so he wanted somebody who would be able to protect and appreciate that humor.

It’s a coming-of-age film about friendship and love, it also keeps that raunchy humor present in your previous work.

That’s just what I find funny, so probably that’s why they sent the script my way. As you say, it’s a combination of the R-rated comedy and the raunchiness, with that incredibly sweet, slightly melancholy story. This combination is quite rare, it gave me a chance to do the things that I’ve done before, along with something that I hadn’t necessarily ventured into previously.

The actors (Ed Oxenbould and Avan Jogia) are terrific. How was the process to build these characters who are so different from each other?

It’s really interesting because in real life they’re very different to each other as well. Avan is very flamboyant as an individual and the life of the party, whereas Ed is quite reserved and shy. They brought a lot of themselves to the characters. In real life they really enjoyed each other’s company, which was not what I expected but very edifying.

Above and beyond knowing that these people can act, it’s really important for me to see the person behind the actor, and know that they have a certain spirit or sense of humor to embody the character. That process of getting to know the actor is essential: even before you get them to read the lines, just have 10, 15 minutes in a room chatting with them to get a sense of the person behind the actor. Doing that with both Ed and Avan, it became apparent that they’d be able to embody Tim and Stéphane fantastically.

It’s a period piece with several references, for example, to the French New Wave.

I grew up in the mid-seventies (Mazer was born in 1971) so all those references were really important to both Tim and I: The Smiths, French New Wave cinema and things like that. They really gave us our cultural identity, when our friends were listening to Duran Duran and watching Arnold Schwarzenegger films or Revenge of the Nerds and Porky’s… I watched all of those things, of course I did, but I also liked to feel like I was different and unique through those similar cultural references that Tim has.

I loved putting together the soundtrack: The Cure, Swing Out Sister, Scritti Politti, things that my older brother actually listened to at the time; he was much cooler than me. Remembering those really helped create that aura of the 80s.

One of the most important themes is racism, present today in a lot of places in the world. How important was it to send a positive message?

That’s what makes this film relevant, it provides the backbone to the story.

It’s similar from the work I’ve done before with Sacha (Baron Cohen), whether it’s Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, Brüno or The Dictator. It’s really important that those have a hopeful message that can be conveyed by comedy, in a way that it reaches people who might otherwise not necessarily hear what we’re trying to say. Using laughter to bring home a message or a political idea is incredibly important and powerful.

It’s depressing that we haven’t really come that far since the 80s and the problems are still exactly the same. We made the movie during the Donald Trump era, so it seemed particularly important. The problems of the 80s were still very much alive in 2020 and I wanted to address that, in the same way we addressed it in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm.

How was it to work again with Sacha Baron Cohen on WHO IS AMERICA? and BORAT SUBSEQUENT MOVIEFILM?

We didn’t make a sequel to Borat for 15 years because it didn’t seem like it was necessary. We didn’t do another show like Da Ali G Show because it didn’t seem necessary. And then Trump came along and was spreading hate, making us angry.

So all of the sudden it felt like an urgency, to get out there and expose as much as we could what he was doing, to say “this isn’t OK,” to maybe reach people who otherwise would be ambivalent about it, to point out his idiocy, his racism, his bigotry. Again, if you can do that while you make people laugh, then you reach an audience that otherwise might ignore it.

Do you consider that nowadays, especially on social media, the “politically incorrect” comedy is under attack?

If you’re racist, sexist or prejudiced in any way, and you’re using that for cheap jokes, then you’ll get exposed. But if you’re coming from a good place where you are using your comedy to expose those things, trying to highlight the worst things in society, then you should probably get away with it.

There’s obviously a lot of noise about “you can’t say anything anymore,” but we made Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, a pretty edgy movie with lots of slightly controversial jokes in it. We managed to make it because we were always very steadfast in making sure that our jokes came from a good place.

The Exchange is now available on demand and digital.