Oldenburg 2020 Review: BUCK ALAMO, The Strains of a Surreal Twilight Song

When your name comes up on Death's list, there's not really much you can do, except wait for him to collect you. Well, maybe not quite for Eli Cody; he might have gotten his fatal diagnosis, but he's not going out fast or easy, or without making sure he's tied up every loose end he can before he lets Death put a hand on his shoulder. Being a musician, Eli sees what he's leaving behind laid out for him as such that he will sing his way out the final door, as he tries to mend what he's broken.

Ben Epstein's feature debut Buck Alamo follows Eli as he comes to terms with his impending death. The subtitle is 'A Phantasmagorical Ballad', and while it veers on the edge of American indie surrealism, it sticks closely to the ballad form, as Eli writes these last chapters while he still has some control over his life. It weaves in and out of a firm grasp of reality, much like Eli's mind, as he finds last moments to savour, and loved ones that will keep his memory alive.

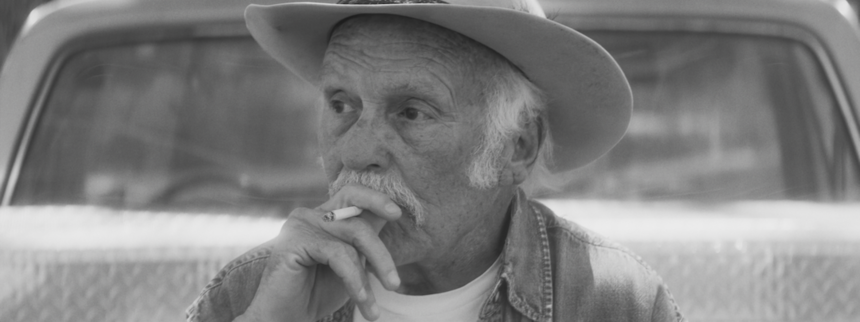

Eli (Sonny Carl Davis) scratches together a small yet not unhappy life and living, singing at bars and his church, and making lamps out of beautiful rocks. He lives next door to one daughter, Caroline (Lorelai Linklater), who loves him and hates him in equal measure. He has a few people around who care about him - Preacher (Kriston Woodreaux), who tries to provide some good council), his young grandson, a few musician friends. Then there's his other estranged daughter Dee, who hates him with quite a fiery passion, and Caroline's boyfriend Levi (Chase Joliet), who drinks and cheats and who needs to heed Eli's words of warning on his behaviour. And all the while, Death (Bruce Dern) is following behind, keeping tabs on these last moments, waiting for the right one to spirit Eli away.

Eli is something of a stereotype of a curmudgeonly old man, set in his ways, true to himself, a bit of an asshole but with a good heart. But it's a stereotype for a reason, and Davis imbues Eli with a deep heart and a soul that is as poetic as it is caustic. He knows that he likely isn't about to change anything for the better before he goes, he just wants to say and make peace. Of course, that's pretty selfish, as daughter Dee (Lee Eddy) points out. As Eli struggles with almost constant pain and difficulty walking, he at least has his loyal dog by his side, even as he questions his life in quiet moments.

The thread of Eli's final days makes for a loose structure, but much like Eli's life, the film is a series of vignettes; some lyrical, some dramatic, some strange and ethereal. These are pieces of his strange and scrounging life: moments with his grandson, as if this is some reflection of his own childhood, when words of wisdom are passed but maybe you won't recognize them until years later. When you sway to the music you sing, words that now have double or triple meanings. When you look to your god in the heavens with both bemusement and something of frustration.

Davis (unsurprisingly) gives a stellar performance of a man's last days, a man set in his ways yet knowing he has to give something before he goes, if only for a bit of peace at the end. Linklater, as his angry yet hard-loving daughter, matches him in subtetly and strength of performance, a woman who matches her father just a bit too much for her liking and yet stands her stubborn ground. Epstein allows each of his actors the breathing space to explore how their characters move in the story he's created, one which moves like a ballad being written with each movement, nobody quite knowing what direction it's going to take, so they take turns at the proverbial wheel to make discoveries good and bad.

Buck Alamo is an understated film, one that creeps over you, like an old musican's final album that speaks as much to themselves as it does the audience. It asks you to lean in closely and listen (and watch) without prejudice or preconception, casting strange lights on the final dark moments of a lifetime.