Film at Lincoln Center and the New York Asian Film Foundation present the 18th edition of the New York Asian Film Festival (NYAFF), which runs from Friday, June 28 through July 14, 2019.

This year's program features another extensive survey of East Asian Films, including five international premieres, 23 North American premieres, four U.S. premieres, and eight New York premieres, showcasing the most exciting action, comedy, drama, thriller, romance, horror, and art-house films from East Asia, and bringing close to 30 directors and nine actors from Asia.

The Opening Night is the North American premiere of Bernard Rose’s Samurai Marathon, featuring a star-studded cast and a score by Philip Glass. Eguchi Kan's irreverant action pop comedy The Fable is the Centerpiece.

The Star Asia Lifetime Achievement Award will go to Hong Kong action choreographer and director extraordinaire Yuen Woo-ping and the festival will honor him by screening three films featuring his work: Iron Monkey, The Miracle Fighters and Master Z: Ip Man Legacy.

Click onward to see our preview picks in the gallery below.

Christopher Bourne

contributed to this story.

Samurai Marathon Opening Night Film

Samurai Marathon dramatizes a little known fact in Japanese history, where the arrival of Commodore Perry, samurais, and ninja spies all take part in a tale of love, loyalty and tradition at the end of an era. An all-star cast, compelling storytelling and technical craftmanship contribute to the film all the markings of a prestige jidaigeki (period film).

The Annaka clan's feudal lord Itakura (Hasegawa Hiroki) is concerned about the readiness of his men upon hearing about the inevitable prospect of foreign invasion because Japan's been enjoying relative peace for the last 300 years. The brash Commodore Perry (Danny Huston) lands on the Japanese shore and offers the shogunate Western trinkets -- daguerreotype, bourbon and guns -- in the hopes of opening up the isolated country. The year is 1855. So Itakura devises a plan.

He will hold a long distance running contest through the steep slopes and reward the winner with whatever they wish. Jinnai (Satoh Takeru), a ninja sent by the Shogunate to spy on the Annaka clan and currently living as an accountant, is alarmed by the sudden mobilization and mistakenly sends a message to Edo to dispatch the assassins armed with a Colt 45. The rest of the movie is a race against the clock as samurais and foot-soldiers alike make a dash at completing the marathon, then, halfway through, realize the assassins are after their town and the lord, so they have to hastily return to save their town.

Samurai Marathon has plenty of intrigue. For example, Itakura's rebelious daughter, Princess Yuki (Komatsu Nana) joins the race in disguise; and Uesugi (Sometani Shota), a lowly foot-soldier who's known for his speed, will need to compete with Tsujimura (Moriyama Mirai), a spoiled but loyal samurai, for the race. There is Kurita (Takenaka Naoto), a retired old guard who brings much needed humor to the film. And Jinnai's loyalty shifts as he realizes his mistake.

With Phillip Glass' rousing score, Bernard Rose, a British director who is known for his vividly visual films (Candy Man, Paper House) deftly plunges into jidaigeki without losing a beat. Many heads will roll, rice fields will be painted with blood, arrows and ninja stars will fly, and bullets will be fired. Samurai Marathon's got everything you need in a great, enjoyable martial arts film.

-- Dustin Chang

Dare to Stop Us

Choosing this title to watch was a no-brainer for me. As a huge fan of Japanese New Wave, Wakamatsu Koji, and his screenwriter and comrade Adachi Masao, I was eager to watch the film. It didn't disappoint. Not only is the film a great reflection of the bustling, energetic Japanese cinema scene of the past that is rarely depicted on screen, it is also an acute observation of a young woman struggling in a male-dominated field.

From the point of view of a 21-year old Shinjuku hippie girl, Shiraishi Kazuya depicts one of the Japanese New Wave greats, Wakamatsu Koji and his gang at the height of their most prolific period, 1969 - 71, which was a socially and politically tumultuous time in Japan.

Megumi (Kadowaki Mugi), a young woman who is still unsure about her place in the world, is a big fan of Wakamatsu's sex- and violence-filled, edgy, politically charged underground films. She wants to be his assistant director because her friend, Spook, happens to be working at the director's tiny production company. Before she gets introduced, Spook warns her that the gig will be tough.

As expected, the notorious director of Embryo Hunts in Secret, I-make-films-that-put-audiences-at-knifepoint Wakamatsu turns out to be a larger than life character. He's loud, egotistical, and always yelling at everyone on set that they are doing a terrible job. Forever donning sunglasses with a cigarette dangling on the side of his mouth, he keeps calling her by wrong names. But Megumi slogs through all the verbal abuses in the predominantly masculine film set culture.

First, her main duty is getting actresses who can pass for High School girls to be in pinku (softcore porn) movies. But over time, her diligence and hard work pay off and she becomes indispensable for Wakamatsu Productions.

In its two-hour running time, Shiraishi manages to make caricatures of these historical figures into well-rounded, likable individuals. He doesn't depict his mentor Wakamatsu as either good or bad, just a human with blemishes like any other. Kadowaki gives a sterling performance as a young woman swept up in exciting, yet dangerous times where certain things were still seen as taboo and frowned upon.

There are many juicy details both behind and on set scenes that will delight the students of that era, including the shooting of Go,Go, The Second Time Virgin on the rooftop from the script from 'that crazy guy Adachi'; Wakamatsu's penchant for making friends with everyone, even the critics and enemies at screenings, bars, and offices; Megumi getting her hands on directing part of Kama Sutra and her first 30 minute pinku film commissioned by love hotel industries; her making advances at the more stoic and gentle Adachi; appearances of studious Oshima Nagisa, Wakamatsu and Adachi's trip to Palestine; and the creation of a traveling screening on a red bus of The Japanese Red Army - PFLP: Declaration of World War, and so forth.

Dare to Stop Us is a sprawling, heady film full of historical and cultural details. It's also beautifully-acted.

-- Dustin Chang

Winter After Winter

Xing Jian's Winter After Winter starts with a 20-minute one-take sequence about the Lao family household, as the patriarch Lao Si (Gao Qiang), desperately tries to postpone the immediate forced recruitment of his three sons by the occupying Japanese army. He is determined to keep his family lineage alive by having Kun (Yan Bingyan), his daughter-in-law, impregnated by one of his younger sons before they get taken away (his eldest is impotent).

The second eldest son, Lao Er, runs away in disgust, joining the resistance in the woods; the youngest Lao San, tries but fails and gets taken away along with his older brother. It is 1944 in rural Manchuria.

So starts a formally rigorous, rural miserablist drama. Shot mostly in black and white, Xing has a keen eye for composition and mise-en-scene. The devastating and inhuman effect of the late stage of the Japanese occupation is deeply felt in every character as they try to survive, especially in Kun. Yan's muted performance as a woman quietly suffering from the follies of war and of men is most touching, without being too melodramatic.

The color comes into the picture only after the end of the occupation, but little has changed for these small folks. Their lives are still harsh under the falling snow, and the color remains muted.

-- Dustin Chang

Hard-Core

Based on a cult manga Hardcore Heisei Jigoku Bros., this wacky film is a collaboration between director Yamashita Nobuhiro (Linda Linda Linda) and versatile actor Yamada Takayuki (13 Assassins, Milocrorze: A Love Story) who also wears a producer's hat. Its sci-fi tinged, overly complicated storyline doesn't quite capture the aloofness of the comic book nor justifies its two-hour running time, but it has its moments and charm.

It tells a story about Ukon (Yamada), an outcast with a bad temper. He works for an ultra-nationalist nutjob whose goal is to find a shogun's gold buried in a mine so he can re-educate today's youth with the money. Ukon meets hulking, homeless man-child Ushiyama (Arakawa Yoshiyoshi) and feels the fang of kinship.

Things slowly change when they find a robot in the basement of an abandoned chemical factory where Ushiyama sleeps. Ukon's salaryman brother Sakon (Satoh Takeru) wants to make money off of the robot, but Ukon threatens him with violence.

The Robot (Robo-o, Ukon calls him), may not speak, yet it's a sentient being and, when necessary, grabs his friends and flies out of danger. Unfortunately, Robo-o is not the main part of the film.

Not quite as crazy as one would hope from a film featuring a guy in a tin-man suit breakdancing, its multiple plotlines don't help the matter much either. Yamashita's distant approach has its charm, though, and Yamada's semi-serious face is a deadpan comedy delight.

-- Dustin Chang

Fatal Raid

No amount of sport bras and flying neck scissor chokes can save this middling Hong Kong actioner fashioned off of Michael Bay-type shoot 'em up visual porn: all shaky cam, discarded shell casings and slow mo fight in the rain kind of stuff.

Fatal Raid involves a raid by an elite HK squad going horribly wrong, resulting in a major friendly fire incident and heavy collateral damage (witnesses are killed), and scarring core members psychologically for life. Twenty years later, the same surviving members are involved in another raid taking place in Macao, now with a new generation of a special force made up of barely distinguishable babe cops.

Things go wrong as they usually do in these movies. They take casualties. And the PTSD comes back on strong to haunt them.

-- Dustin Chang

Jinpa

Pema Tseden occupies a unique place on the world cinema landscape, as a Tibetan director working within the Chinese film industry, telling stories about his people that dispense with the usual idealized, pious stereotypes of other depictions of Tibet onscreen, offering a much more realistic insider's view. Tseden's sixth feature, Jinpa continues this artistic mission, injecting sly deadpan humor and a touch of the surreal to deliver a deceptively minimalist, existential road movie that meditates on karma and cycles of revenge, stylistically owing as much to classic American westerns as to Tibetan Buddhist philosophy.

A truck driver named Jinpa (also the name of the actor who plays him) is traveling along a desolate stretch of road on the Kekexili highlands, when he runs over a sheep, an accidental act that nevertheless makes him feel deeply guilty. Along the way, he picks up a stranger (Genden Phuntsok) hitching a ride to a nearby town. After initially dodging Jinpa's queries about the purpose of his travels, the stranger reveals that he plans to murder his father's killer, a man he's been searching for the past ten years. Jinpa and the stranger part ways at the latter's destination, but Jinpa continues to be haunted by the juxtaposition of the sheep's killing and this stranger's murderous plans. The fact that the stranger is also named Jinpa is another haunting connection.

All this sets into motion the journey that constitutes most of this film, one that has Jinpa encountering a number of fascinating characters, most intriguingly in a truckstop bar that has the feel of a saloon straight out of a John Ford Western, where he interacts with the flirtatious barmaid/owner (Sonam Wangmo). He's gone there to look for the other Jinpa; it's unclear whether it's to stop him from killing or just to see if he's gone through with the act. Tseden imbues all this with a mesmerizing, slow-burn quality that combines the sharply observed realism of his previous work with a dreamlike, surreal mysticism.

-- Christopher Bourne

The Gun

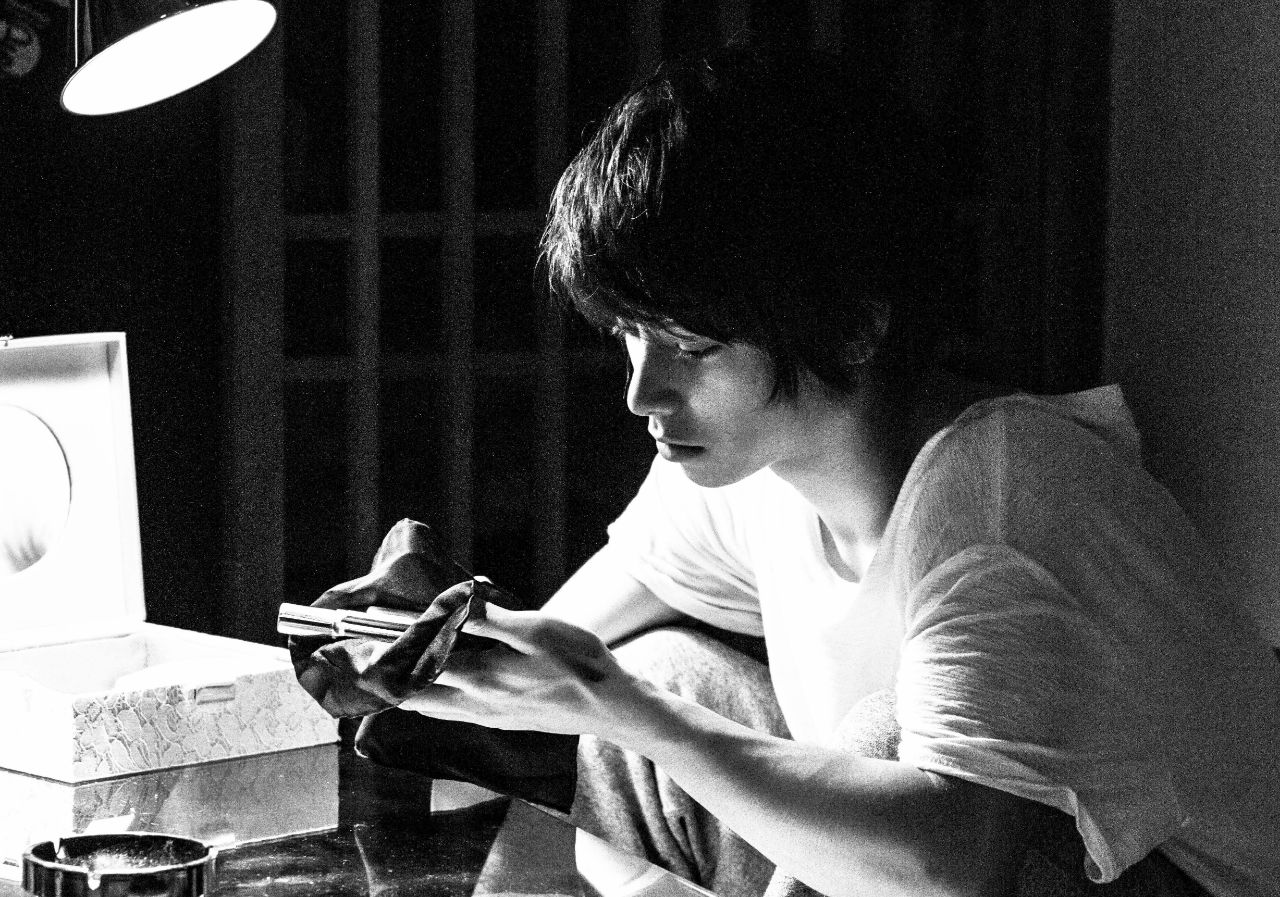

Masaharu Take's latest film, adapted from Fuminori Nakamura’s novel, has influences that are myriad yet smoothly complementary: American film noir, 1960s Japanese New Wave, Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Camus’ The Stranger. But Take makes his film feel less derivative and more contemporary than these antecedents would suggest, despite most of it being filmed in black-and-white, save for the final scene.

The film's protagonist, college student Toru (Nijiro Murakami) comes upon a dead body by the riverside one night, and impulsively snatches the gun lying next to the dead man and takes it home with him. This unthinking act sets the entire rest of the narrative into motion, as the possession of the gun transforms his psyche, bringing to the surface repressed instincts, pushing him into ever more extreme types of behavior.

The Gun challenges viewers by keeping so close to a character who often acts like a self-absorbed jerk. Women prove to be particular victims of Toru's selfish behavior, both the woman with whom he's having a sex-only relationship (Kyoko Hinami), and his classmate Yuko (Alice Hirose), who confides her deepest feelings to him. This points to the film's greatest weakness: the female characters seem to be little more than accessories to the central character, with very limited agency of their own.

What makes Toru's possession of this gun even more reckless is that it's a .357 Magnum, rare in Japan and thus easily traceable by police. So inevitably a detective (Lily Franky) comes sniffing around, raising the stakes of discovery for Toru.

The Gun has an initial existential, detached air that gives way to a growing sense of dread as Toru loses his grip on self-control and reality, leading to a conclusion that's no less shocking because of its inevitability.

-- Christopher Bourne

The Rib

Considering the recent headlines concerning Chinese films being pulled from festivals at the last minute and denied releases in their home country (for absurdly euphemistic “technical reasons”), it's all the more remarkable that a film like Zhang Wei's The Rib exists. This is a film that laments the marginalization of China's transgender community, positively affirming their right to exist and live as they please, which managed to pass governmental censorship. (A back-patting closing title card touts recently instituted progressive government policies regarding the legal status of transgender people.)

Zhang specializes in socially conscious films that focus on marginalized groups in China, and The Rib is completely in keeping with his concerns. The initial focus is on Huanyu (Yuan Weijie), who has long identified as a woman, and wishes to undergo gender reassignment surgery. Although Huanyu has a group of supportive friends, particularly Liu Mann (Gao Deng), who recently had this surgery in Thailand, she also faces strong opposition from her father (Huang Jinyi) and his Christian church community. Huanyu’s father is also an impediment to the surgery she seeks; signed parental approval is legally required.

Filmed in stark monochrome, save for one significant recurring splash of color, The Rib is a sensitively crafted and moving work, equally critical of societal discrimination and the hypocrisy of a church that preaches love yet cruelly rejects those who don't conform to their narrow moral strictures. And although a major character meets a tragic end, the film laudably resists portraying grim tragedy as the default mode of the lives of transgender people, showing the fun and camaraderie that also exists. The most moving passage is a final sequence in full color, simply consisting of those finally allowed to be truly seen.

-- Christopher Bourne

Another Child

Actor Kim Yoon-seok (The Chaser, The Yellow Sea) makes an impressive debut as director with Another Child, which centers on two high-school girls – Joo-ri (Kim Hye-joon) and Yoon-ah (Park Se-jin) – classmates and frenemies who discover that Joo-ri’s father (Kim Yoon-seok) is having an affair with Yoon-ah's mother (Kim So-jin). Inevitably, Joo-ri's mother (Yum Jung-ah) learns of this affair as well. Things get even more complicated when Yoon-ah's mother becomes pregnant as a result of the affair.

On the surface, this all seems like TV soap opera material, but what elevates it far above that sort of thing is the beautifully written script (by Kim and Lee Bo-ram), which perceptively tracks the contours of how this affair affects everyone involved, and refuses to demonize any of its characters. Great performances and understated yet elegantly staged filmmaking complete this fine package.

-- Christopher Bourne

Furie

The oddly spelled title of Le Van Kiet’s Vietnam-set action flick says it all. Veronica Ngo, an action star in her native Vietnam (whom fans of recent Star Wars films may recognize), plays Hai Phuong (the film's Vietnamese title), racing against time to save her young daughter from a child trafficking ring harvesting organs from these kidnapped kids.

That's pretty much all the important narrative information you need to follow this Vietnamese, woman-led riff on the Taken franchise, with Ngo wearing the one expression of steely determination she wears throughout the film. There's more backstory to this, but it all proves as ultimately disposable as the entire film is.

That's not necessarily a bad thing; there's always a place for uncomplicated, diverting entertainment. If anything, there's too much story; it delays and distracts from what you're there for, which is ferocious ass-kicking, and for that matter, every other body part-kicking. The final section does deliver that, shorn at last of excess narrative baggage. Modest and derivative Furie may be, but it certainly meets the goals it sets for itself, which at least is more than can be said of many other films.

-- Christopher Bourne

Around the Internet

Recent Posts

SCREAM 7 Review: Well, That Was Brutal

Leading Voices in Global Cinema

- Peter Martin, Dallas, Texas

- Managing Editor

- Andrew Mack, Toronto, Canada

- Editor, News

- Ard Vijn, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- Editor, Europe

- Benjamin Umstead, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, U.S.

- J Hurtado, Dallas, Texas

- Editor, U.S.

- James Marsh, Hong Kong, China

- Editor, Asia

- Michele "Izzy" Galgana, New England

- Editor, U.S.

- Ryland Aldrich, Los Angeles, California

- Editor, Festivals

- Shelagh Rowan-Legg

- Editor, Canada