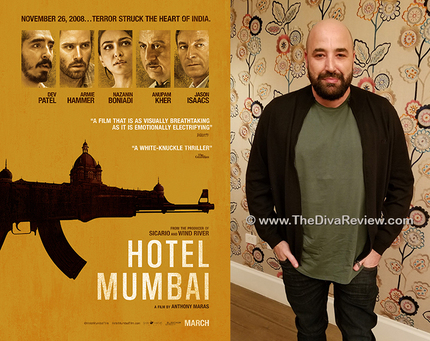

HOTEL MUMBAI Interview: Director Anthony Maras on a Plea for Peace

On November 26, 2008, a multi-pronged attack of unfathomable destruction and carnage seized the city of Mumbai, India over three days. Amidst the chaos, unarmed common people of all faiths and races banded together to survive the terrorist onslaught.

Hotel Mumbai is one such story of how a courageous staff protected their guests and each other and inspired the world. Director Anthony Maras discussed the responsibilities of telling this true tale, and its plea for peace.

The Lady Miz Diva: You came from a background of short films. What was it about the story of the Mumbai terror attacks that made you want to centre your first feature around them?

Anthony Maras: It really came about after watching this documentary called Surviving Mumbai. Prior to having seen the documentary, I didn’t know too much about the Mumbai attacks. I knew as much as most other people; which was seeing a bunch of anguished faces on television, burning buildings, and some of the things that we are “used to seeing” during these terrorist attacks.

However, seeing the documentary opened up a different angle to the attacks and to people’s responses to them, and that was the human angle, the human story. Which is to say, because the attacks took place over a sustained period -- it was a three day period -- it wasn’t like other terror attacks, where there might be a bomb blast, or shooting, and it’s jarring, and it’s violent, and it’s over, and you’re dealing with the aftermath.

In the case of the Mumbai attacks, over 68 hours meant that the human response quite different; meaning that because Mumbai is such a huge city, and because it took time for the police to be able to neutralise the situation, a lot of people caught up in the attacks had to rely on themselves and one another to get through this ordeal.

And particularly what you saw at the Taj Hotel, was a situation where you had people from all different walks of life, from many different religions; Hindus, Christians, Muslims, people from vastly different socioeconomic backgrounds. You saw all these people forced to come together, and protect one another, and be there for one another to get through what was quite a horrific ordeal. The example that was set by the guests and particularly the staff of the Taj Hotel really inspired me to tell the story.

In the case of the staff members of the Taj, you had people who had families of their own, who had husbands and wives and children outside of their work, and despite that, they chose to remain to protect one another, and to protect their guests. In some cases, you had staff members who had successfully evacuated people from the building, who then, unbelievably, chose to come back in to go in and help their fellow people. I kept asking myself, as surely you would, ‘What would I do in that situation?’ and that was the impetus that really began the project that was Hotel Mumbai.

So, it started with viewing the documentary, then my cowriter, John Collee, and I, watched dozens of hours of interview footage -- the unedited footage that didn’t make it into the documentary, and we were just sort of overwhelmed by these immensely human and heroic stories of people coming together. These are heroes who never fired a gun, they never threw a punch, and the heroism came through their ability to be there for one another, to keep calm, and to quite selflessly do things, like when escape attempts were made.

You had people like Daniela Federici, who was an Australian photographer caught up in the attacks; we’d interviewed her. She and her friends had been trying desperately to keep quiet, and as the building was burning, they had to get out, it was only when a grenade had gone off and cracked one of the windows that they were able to then get a champagne bucket and crack the window. Then they had to wait patiently and lower one another out of the window with curtains instead of ropes.

You had other instances, like the kitchen staff that was headed by Hemant Oberoi, the head chef, who was stuffing pots and pans and baking trays down their shirts to act as makeshift bulletproof vests, to protect one another and their guests as they were making these escape attempts.

Really, more than anything, these barriers that we’re often told in media and other places that usually divide us, evaporated at the Taj, and through the Mumbai attacks, and people came together to survive.

LMD: How did you go about researching the story? Did you interact with the actual survivors and witnesses?

AM: Over the course of about 12 months, we conducted our sort of research -- it was ongoing, as we were making the film, because as you make it, more and more stuff feeds in -- but it started with a friend of mine who is a lawyer in Australia, Brian Hayes, he’s since become a co-producer on the film.

Brian was born in India, later educated as a lawyer in England, but ended up in Australia acting as a lawyer. In his other life, he runs trade missions between Australia and India; cultural exchange programs, and also is a patron of various charities. I’d gone to Brian very early on, to say, “We’re looking to do this film about the Mumbai attacks, and I want to get as much information as possible.”

Specifically, I was after the court case transcripts of Mohammed Kasab, who was the sole surviving terrorist. These documents are publicly available, but in Australia, you can get the judgments, but to get the entire transcript can be difficult.

So, Brian helped to source and introduced us to both the prosecutor, the defense counsel, and he also knew the judge in the case, but it was the defense counsel that directed us to where we could find the court case transcripts, and within them was thousands of pages of the confession of the gunmen, together with a lot of other circumstantial evidence, including these satellite phone calls that were intercepted by the Indian security services.

These were calls that were made between the gunmen and their handlers back in Pakistan, and that give a blow-by-blow account of what they were saying to one another, and what they were being told by their handlers, and some of that interaction made its way into the film.

So, before we went out and did any interviews, John Collee and I went through all of this interview material that the original documentary makers had made. We went through all the transcripts, we had a very close working knowledge of the details of the attack, but then we spent 18 months going in, interviewing real-life survivors.

So, we went to India; we spent over a month staying at the Taj hotel, and between India, Australia, and America, and in person we interviewed people, and then various people by phone, and by Skype video chats. We interviewed over 40 people to get their perspectives on what they had endured, and what they had gone through. These were predominantly focused on people who were at the Taj hotel, we also interviewed others who were caught up in other parts of the attack.

And I’m not counting those within the 40, the other people interviewed included the two police officers made their way into the CCTV, and obviously, Hemant Oberoi, and many other people, within the Taj/Oberoi trident of hotels and other places around.

LMD: When you are dealing with a recent tragedy, particularly one where those involved can respond to what you’ve presented onscreen, does that affect your perspective or approach as a filmmaker?

AM: Of course. There’s a huge sense of responsibility that you have to do justice to their stories. These were very difficult times, and so, for us, it was very much a process of listening, not making any judgments, and spending a lot of time just trying to absorb what had happened, and it was from that the story and the script came out of.

LMD: While HOTEL MUMBAI is based on a true story, the events of the anti-Muslim terrorist attack that just occurred in New Zealand are horrific and devastating. I wondered if you reached out to any imams, or Muslim community leaders about how to present the Muslim characters?

AM: We didn’t speak with any imams, or Muslim community leaders; we focused our attempts specifically on the people who had endured the attacks.

First, about New Zealand, I’m horrified about what happened there. My heart goes out to the families, and the victims, and to everyone affected. It’s horrifying. Our film is not anti-Islamic, it’s anti-extremist, and extremism has many different clothes, and many different cloaks.

It happened to be at the Taj that there were Islamic terrorists who had done this; but I think the film is really about people from all walks of life coming together. Within the Taj, there were people of all ethnic and religious persuasions, and you had people of the Muslim faith, of the Christian faith, and the Hindu faith, coming together within those walls to survive against extremism.

And so, the film is a plea for peace, and it’s a major indictment against using violence. Again, our heroes never throw a punch, never fired a shot; they are heroic in how they showed calm and unity.

We’re often told in the media exactly at points like right now, that there’s all these things that divide us. What happened in the Taj shows that it doesn’t have to be like that; that these barriers that can exist, they evaporated over those three days. You had people from different cultures, religions, ethnicities, socioeconomic backgrounds coming together, standing up to extremism. I hope that is the message that is taken away.

On a separate note, if you look even within our film, the young gunmen that go in, go in devout in their beliefs. The main one that we focus on over the course of the film comes to see that he’s been sold a crock of lies. It’s when the young Muslim woman stands up, and without any weapons, stares in his face and uses her Islamic faith as a source of strength and comfort, that she defeats his extremism, and his warped view of his own religion. She defeats that with her purity.

That happened. That moment, that’s not a fictional invention. Watch Surviving Mumbai, that happened. It didn’t happen specifically to the character we have; she’s an amalgam, but you had during the course of the Mumbai attacks, a hostage who stood up and recited her surah whilst the handler was saying into his ear, “It doesn’t matter, kill her anyway,” this young gunmen realised his own hypocrisy, and pretended to fire and left, and they live now, those hostages, they lived.

LMD: Arjun is a Sikh, and we don’t see too many on screen, and certainly not in a heroic role. I love how we meet him carefully arranging his dastar, and see some of the misconceptions and prejudices he faces as a Sikh. He’s presented so respectfully I was curious if you researched that faith, and whether you helped guide Dev Patel’s performance with research cues?

AM: Of course. The Taj Hotel has Sikhs as doorman, as ceremonial guards throughout all their hotels. They are traditionally, historically, a warrior class. At all the hotels, you will see men with the dastar and the beards at the front. I personally felt, after Dev’s idea, actually, that to show to not judge a book by its cover; and there were incidents after 9/11, and after that, there were people were sort of praying and attacking Sikh Indians in response to Muslim attacks.

It’s ignorance that is the problem, it’s a lack of education that is the problem. It’s the fact that people see “the other,” and they’re scared of what they don’t know about. I guess the example of what happened within the walls of the Taj, is that these people came together, and I think that is a very powerful message that the world could do with right now.

LMD: I’m curious as to David’s place in the film? I felt that Dev Patel’s Arjun character was kind of the superhero of the piece, yet the camera lingers on Armie Hammer’s David. What did David’s character represent?

AM: The fact is that the Taj is an international hotel, and the victims came from all walks of life. There were Indian victims, there were foreign victims, there were American victims, and you can’t do justice to the story without acknowledging the fact that people of all colors and all types were affected negatively by this.

The David character was based on real life persons; a husband and wife, who wanted nothing more than to survive this, so that their child wouldn’t become an orphan. And even though they wanted more than anything to be there for one another, had they been in the same physical proximity, there would be a greater risk of both of them dying.

So, they had a really impossible decision to make; which was separate and have a chance that one of us lives, or be together and a greater chance that if the floor above them caves in from a bomb, or if someone comes through the door and shoots, then their child becomes an orphan.

These were questions that I kept asking myself throughout the course of making the film, ‘What would I do from that situation?’ In the end, the film is an attempt to place people in the shoes of those who lived through this experience.

LMD: You mentioned the research that you did with the survivors and those affected by the Mumbai attacks. Have any of them seen the film, and what has been their response?

AM: Several people have seen it. We had Hemant Oberoi see it prior to the Toronto screening. I was very nervous about how he’d take it, because obviously, you put your heart and soul into this and try and do justice to their stories, but ultimately, the response they’re gonna have is the response they are gonna have.

I called Oberoi shortly afterwards, and he said, “This has captured what it felt like for me to live through these attacks.” Then, he was our special guest at the Toronto film Festival, and you can see online, where there was a standing ovation for him.

I had been working with others, like the photographer, Daniela Federici, who was caught up in the attacks; we had actually used some of her footage in the end of the film. She was present at the Toronto screening. We also went back to India in December, and held a private screening for the management of the Taj, and for some of the survivors, and that was a very emotional experience. I found a very moving.

Look, I’m sure there were going to be people who lived through the events where it’s too difficult for them to face this; I guess all we can do is try and respectfully construct a story which is going to touch people’s hearts, and show that people coming together to find a common humanity despite -- or because of -- the difficulties they face, and the horror that they go through, is an inspiring message.

This interview is cross-posted on my own site, The Diva Review. Please enjoy additional content, including exclusive photos there.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.