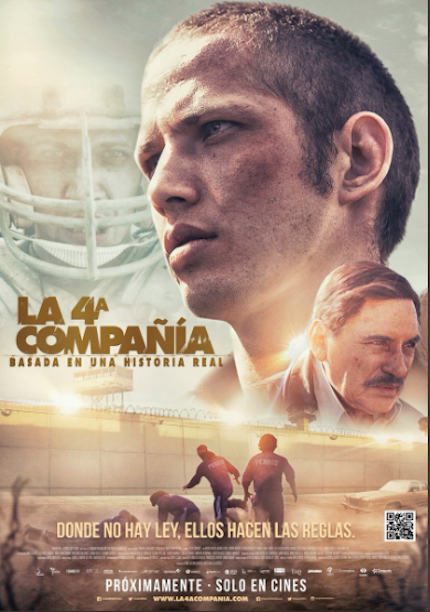

Review: THE 4TH COMPANY, Prison Football As Coverup Of A Criminal System

Arguably, this is one of the very few above average Mexican films so far this year.

The 4th Company (La 4ª Compañía) gained attention last year when it won several Ariel awards (the Mexican equivalent of the Academy Awards), including Best Picture; it was particularly notorious because practically no one had seen the film at that time, as result of the always conflicting film distribution process in Mexico. It’s been almost a year since that happened, but The 4th Company was finally released last week and is, arguably, one of the very few above average Mexican movies so far this year.

On paper, The 4th Company might sound like the Mexican version of The Longest Yard, that 1974 picture in which a former football player (Burt Reynolds) is put in jail, where he becomes the leader of a team of other prisoners and trains them to play against a team of guards.

Based on a real story, The 4th Company is, indeed, about a prison football team called The Dogs (Los perros), which in the late seventies became a representation of progress for the Mexican penitentiary system. Los perros will eventually play the final game against the police football team and the overall development of the match is quite similar to that of The Longest Yard (i.e. at one point The Dogs are told to lose the game); however, The 4th Company is really a different beast, to the point that is impossible to call it a straightforward sports movie.

There’s a reason why the nearly perfect season of The Dogs is reduced - without counting the final game sequence - to a couple of scenes and a montage: in this film, football is only the coverup for something much more turbid, a complete criminal system. Actually, our main character Zambrano (Adrián Ladrón), the classic new young man in jail with a strong desire to play for the team, is evaluated not for his football abilities, rather for his experience in auto theft; by proving he can steal a car within seconds, he is welcomed to join the team.

From this scenario, The 4th Company works as an exposure of what went on during the late seventies inside the Santa Martha prison (in Mexico City), where the “privileged” group called The 4th Company, composed of officers, jail employees and prisoners (The Dogs), took over and established their own rules to keep everything “safe” around. The Dogs could enjoy a party with women, or aspired to freedom by winning the football championship, however if one of them failed in the field and needed to redeem himself, his superiors could order him to eliminate another inmate. The success of the football team, representing progress and better conditions for the prisoners, certainly contrasts to the ugly and secret underworld of corruption, thefts, and murder.

While The 4th Company aims to tackle social realism - it was filmed inside the Santa Martha jail and several real prisoners appear as background characters - it also has a clear influence of stylish crime movies, not to mention that is goes full seventies with the look of its characters and soundtrack; it’s not really an action film, nor a heist movie, but there are elements from both types of pictures, for instance.

The script itself aims at different directions and characters, and that’s precisely where the movie’s flaws are more exposed. There are some underdeveloped plots; for example, character Combate (Andoni Gracia) is basically stealing money from The 4th Company and taking it outside of prison with the help of some gang members. There’s a scene in which he writers a letter to the rest of his teammates confessing this and telling them about the money and how it could help them, but it is never clear what happens with said letter.

That said, The 4th Company manages to fulfill its general objetive and, at best, does it in a powerful way. The key to the movie is to understand it as the cinematic equivalent of uncovering the brutal crime underworld with roots inside the institution that supposedly means reform. I just said some of the character arcs feel incomplete, but others are more than just effective; they are striking and relevant. There’s a prisoner whose pain comes from the fact that he’s not seeing his daughter grow. His destiny is not pretty at all, exposing the cold blood of most of the people in the system and even echoing the current issue of forced disappearances in Mexico.

It all perfectly contrasts the inherent joy of the apparent feel-good sports drama in which the underdogs end up winning. That was just the facade of The Dogs' real-life football adventure, and is only the surface of its worthy film version.