London Indian 2014: ANIMA STATE Is A Transient Trip Through Modern/Medieval Pakistan

As a nation, Pakistan was forged from the explosive dissolution of the British Raj in India. In 1947, The Partition drew a fiery line in the sand pushing Muslims of Indian origin to the Pakistani side, and Hindus to the Indian side. While the conflict between the religions was always present, The Partition essentially forced both sides to double down. Riots and mass killings ran rampant, territorial wars persist to this day along the hazy borders of Punjab and Kashmir, and the border between the two nations is one of the most heavily militarized in the world, which each side just waiting for the other to blink. The collective psyche of the Pakistani people has not been left unaffected by this constant state of hyper-vigilance, and Khan understands this quite well.

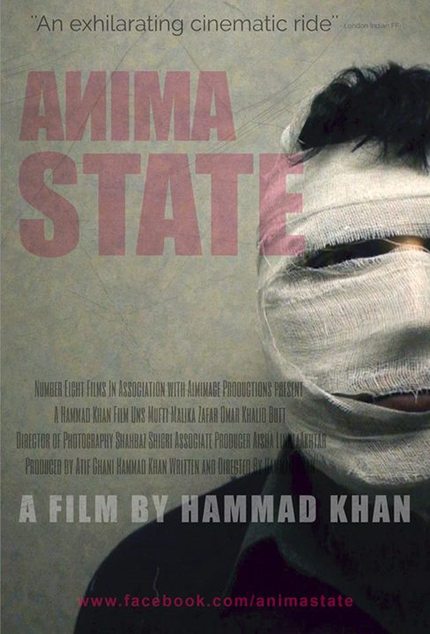

The film opens with a traveler, nameless and faceless, with his head wrapped in bandages stepping out of a car and shooting five twenty-something Slackistanis leaving a cafe. No one screams, though they walk through a crowded park, no one runs, it's just another day. When the traveler, who says he wears the bandages to keep his head from exploding, attempts to turn himself in to the police, he is met with something like apathy, but perhaps even more sinister, he is met with denial. Not only denial of his crimes, but an essential denial of his existence. This man guides us through the Pakistan's past with interspersed archival news reels, clips from old Pakistani films, and voiceovers from Pakistani leaders insisting upon the supreme rule of Islamic law in the nation in order to make good on its reason for being, not unlike American Constitutional constructionists.

He presents us over and over again with paradoxes that challenge the viewer to simultaneously empathize and villainize the common people who can't understand their own actions. The man who beats his wife to keep her in line, "not too much, but just a little", because he's been taught that the Qu'ran gives him that right. The woman whose child suffers a mystery ailment which she cannot get treated because her husband is a worthless drug addict. But most of all, the traveler is a man of contradictions. He kills those that he feels he should by virtue of their deviation from strict Islam, though his confusion is plain, even without facial expressions to help the audience follow.

When a kindly older man takes the traveler into his home, and shares it for the night, we see just how well conditioned he is to be happy when he's supposed to. The older man offers him some weed, and they smoke together, enjoying one another's company, but when the host leaves the room for a moment and puts on a cricket match to entertain the traveler, the Pavlovian response of the guest is not to watch and cheer, but to masturbate. This is the glory that the government has trained him to worship. If Pakistan can be an international powerhouse of cricket, the government must be doing something right. Sports are the opiate of the masses when religion becomes too violent.

Not too on the nose, but perhaps a bit obtuse for the viewer without more than a passing knowledge of Pakistan's history, Anima State presents us with contradictions and asks the viewer, "could you live like this?" The answer is left up to you. However, Anima State isn't done with its viewers just yet. Not unlike the similarly avant garde Gandu, from Bengali filmmaker Q, Anima State switches gears in the final reel to take a different perspective on the whole mess.

The traveler is now the filmmaker, an ex-pat who has returned to Pakistan from what seems like a long leave. The filmmaker enjoys revisiting his memories of his childhood home until he is confronted by the realities of life in Pakistan one by one. Accosted first by police who have nothing better to do than to give people shit, and then by local hipsters who throw around internet jargon as though it's the only language they speak. The filmmaker realizes that the home he left, or was taken from when his father "escaped", has no place for him.

Anima State does a wonderful job, even without a formal structure, of imbuing every scene with a feeling of emotional disconnect. What is happening to the characters, what they are doing to and with each other, doesn't even seem to make sense to them. The dichotomy of a Pakistan pulling in two different directions, one side fighting with guns, and the other with ideas, is ever-present. Hammad Khan has done something special here. Anima State is alternately discomforting, humorous, preachy, illuminating, and abstract, but the whole certainly equals more than the sum of its parts. Pakistanis are people, but as a people, Khan seems to see them as eternally and impossibly conflicted. If you need a story to keep your attention, you might want to look elsewhere, but if you want a film that will make you feel, or more importantly feel empathy, Anima State is a solid choice.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.