Fantasia 2010: A HOLY PLACE Review

We cinephiles suffer from an irrational obsession. It's an insatiable lust for obscurity and esotericism, the nagging need to locate that one ultra-rare picture by that Korean director from the seventies that everyone's forgotten, the uncontrollable urge to see the last surviving 16mm print of Godard's discursus on Maoist colonoscopy. When, just over a month ago, the New Zealand Film Archive discovered a treasure trove of long-lost silent films, including a John Ford production and a Clara Bow period picture, we experienced a collective petite mort. And when A Holy Place showed up at the Fantasia Festival - "the version of Nikolai Gogol's short story Viy that foreign audiences have barely ever seen," says the festival guide - we all came out to have a look.

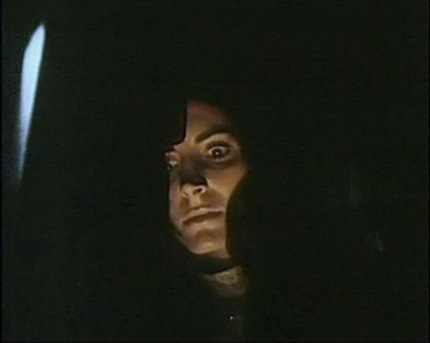

Shot in the Yugoslav countryside in 1990 as the shit dangled

menacingly above the fan, A Holy Place's

negatives ended up shanghaied in a Croatian production facility, a hostage to

the ethno-nationalist insanities of its time. The slightly faded 35mm copy we

saw at Fantasia, in the film's first public foreign screening, was a one-off

print intended for potential distributors. It was never meant for mass

consumption, and it showed. The print was dark, lacked colour collection, and

featured subtitles that wriggled about the screen in the moribund scrawl of a

harlequin fetus, bearing bizarre and, on occasion, serendipitously comical

spelling mistakes ("you are mush too old for me," utters our hero to the

grizzled and rather amorphous geriatric pining for his pud).

Given a properly titrated dose of camp, such lack of

professionalism is not only excusable, but endearing. A Holy Place, with its synthesizer soundtrack coming a decade too

late, punctuating moments of terror with a flatulent waveform and a preciously

digitized flute, would seem to be a plausible candidate for kitsch immortality,

but it just doesn't measure up. It begins as a classic, though transplanted,

retelling of Gogol's story, following three theology students as they trek

through the countryside. When they spend the night at the house of an aged

peasant woman, she attempts to seduce one of them, only to be beaten and left

for dead. Soon enough she has her vengeance, transforming into a voluptuous

young witch who haunts our prospective priest, forced against his will to pray

over her spontaneously reanimating corpse for three tortured days.

And tortured they are. A Holy Place is practically defined by its banality. The budget here is obviously Balkan in scale, but that doesn't mean we should give director Djordje Kadijevic a pass for a lethargic camera that meanders about his characters in near-permanent medium-long shots. There's just very little going on here. The few moments of levity - the priest's forest romp with his elderly seductress is worth a laugh or two - are largely offset by the leaden weight of the film's essential dullness. Even Kadijevic's main deviation from Gogol's original plot, a psychological interrogation of the origins of the witch's evil powers, is largely unmotivated and unbelievable. His characters, especially the women, who serve mostly as emasculating foils, are afforded no psychological credibility. They just don't talk, or act, enough for us to care.

Those of us who went to see the film as part of Fantasia's "Subversive

Serbia" series were animated by the promise of finding the diamond in the

rough, that rare and precious film that, by the accidents of history, has gone

unremarked, waiting for our fortuitous discovery. At times, this passion pays

off: Witness the recent wave of rediscovery of Japanese Art Theatre Guild

pictures from the 1960s. But more often than not, those films that have fallen

from grace, or never attained it in the first place, are shunned with good

reason. The false revelation of A Holy

Place is a case in point, a film so utterly unremarkable that, as I type

these words, it strikes me as paradoxical that I'm remarking it.