CIAO—Interview With Yen Tan and Alessandro Calza

Earlier this year during Frameline 32 when I mentioned to friends that I had invited Alessandro Calza—one of the leading actors in Yen Tan's Ciao—over to my house for wild rice sour cream waffles, they tried to invite themselves over … and it wasn't for my infamous wild rice sour cream waffles! Fortunately, my withering glance was more than enough to keep them at bay so that I could conduct my interview with the film's director and lead actor with a certain measure of professionalism; though I have to admit that the informal quality of our conversation made for a much more pleasant experience. Ciao was one of my favorite films from Frameline 32. It's now in its theatrical run and though—as indicated by Dave Hudson's aggregate of reviews at The Greencine Daily—the critical response has not been altogether favorable; I can, without hesitation, assert that some of the reviews have likewise not been altogether fair. An eye should be kept on the fact that a gay film with any crossover appeal whatsoever—a feat uniquely (unfairly?) negotiated by gay filmmakers—is cause for commendation. Yen Tan's film is more than competent in this regard and such an accomplishment shouldn't be deminimized. I suppose my impatience with some of the film's dismissive reviews is because they underplay the fine achievements by cinematographer Michael Roy, film editor David Patrick Lowery, and production designer Clare Floyd DeVries. Ciao represents yet another example of the great divide between critics and audiences, having been quite well-received at Frameline 32.

Michael Guillén: Alessandro, one of the things that first struck me about this project was how far geographically you two were from each other—Yen in Texas, you in Italy—how did your creative collaboration begin?

Alessandro Calza: Thanks to downloading movies at a site in Italy, I saw Yen's first movie Happy Birthday. A lot of movies aren't distributed in Europe and you'd never be able to see a film like Yen's first movie or a movie like Tropical Malady if it weren't for downloading them. Purely by coincidence, I was checking around and I found Yen's website with his contact info. I don't know why I decided I wanted to write him; but, the fact that he was visible with his web site and accessible through email seemed like he was waiting for people to give him feedback on his movie, which usually doesn't happen with directors. Half the time you don't know who they are or where they are. So I wrote Yen and I told him that I really liked Happy Birthday, which I still like very much. Then we just started talking by exchanging email. He seemed really flattered.

Yen Tan: This was back in 2004, so it was quite a while ago.

Guillén: And then you checked out Alessandro's website and nearly fell over, right? [Laughter.]

Calza: Actually the problem—and the good thing—with Yen and I is that we both like the same type of men, who are very different from the way we both are. That made me comfortable so we could develop a real friendship.

Tan: We weren't trying to get into each others' pants or anything. It was completely platonic. Every time we tell this story, people always go, "Nooooo…!"

Guillén: Why I ask is because the online phenomenon—in terms of film culture—has a unique potential for sociality and fraternity. I've met many writers on line who I later meet at film festivals and it's created a society that wouldn't have been possible if I'd just met them here in San Francisco. So, joking aside, what intrigues me about your collaboration is that you were able to use the online medium as a creative platform. Can the two of you speak about how you came up with the story and how—despite geographic distance—you hammered it out to become the film?

Calza: Yen was working on a trilogy at that time. He was developing three scripts simultaneously. But we became close talking about what we liked. I had a background in European cinema—Tarkovsky, Fassbinder, Wim Wenders—and he was more informed about contemporary directors. On the other hand, I was very much into music so we started exchanging ideas.

Tan: The script for Ciao came out fairly effortlessly. It was created at the same time that I was talking to Alessandro. I was consciously using him as the model for the Italian character. I was having a lot of problems having a film made at that time, getting it off the ground, financial issues and all that, so at that point Ciao was actually supposed to be a sexy fluffy romantic comedy revolving around an exotic Italian guy who comes to America.

Guillén: I am so glad you worked that one out.

Tan: But it was the kind of film that we would have had an easier time making several years ago; though I would have been embarrassed years later. Afterwards I might have thought, "Why did I make that film?" At the time I wrote it, that wasn't in my mind. At that point I just wanted to get something made. I didn't care what it was. Thankfully, when I sent that draft to Alessandro, he was hard on it and told me exactly what he thought. Mostly he criticized the character I'd based on him. That's when I thought maybe I needed to step back and think it through a little more.

Calza: Yes, because the stereotype is that—when you have an Italian in American cinema—he's usually like Antonio Sabato, Jr.; a gay bartender from Miami with an Italian background. He's always what people from Iowa think an Italian should be and what he looks like. For me that wasn't quite right. Also, for the purpose of the movie, such a character—with the focus on clothing and style, wearing silky shirts—would have been distracting. So I was critical about the character.

Guillén: Did you send Yen back an alternate script? Did you rewrite it?

Calza: No, no. We just discussed it. At that time I wasn't trying to interfere with the writing. We weren't even at the stage of my being able to do a rewrite or even auditioning for the part. That came way later.

Tan: It was just something that I wrote that I showed Alessandro. He gave me his thoughts and I reconsidered.

Calza: At that time I didn't yet know that with Yen you had to be very careful because everything you say could end up in his movie. I wasn't aware that every personal detail I shared with him would end up in a script.

Tan: Then I wrote another draft, which was still like the first draft, only a little bit better. At this time, other gay filmmakers were getting their films made and—after watching them—I thought, "Maybe I don't want to make a film like that. Maybe I really need to be careful about what I do next because there may be a permanent scar on my filmmaking career."

Guillén: Your sensibility as a filmmaker, and specifically a gay filmmaker, developed more breadth?

Tan: Right. I thought, "Okay, maybe I need to continue on this path and see what I come up with instead of trying to do something commercially viable that, over time, I might not be happy with." Especially when you're doing a low budget film, the point is to take risks. If you can't take risks with just a little money, then what's the point?

Guillén: Creativity frequently rides a bare bones aesthetic. Roughly, then, how many drafts were there between the sexy rom-com and the movie in Frameline?

Tan: Roughly 10 drafts. Even up to the point when we began shooting, there were still some scenes where I was on the fence. I would rewrite them overnight, give them to the actors the next morning so they would have a little time to rehearse, or I would take scenes out altogether. I don't know if it's because of the way I am, but I have this way of writing where it's very sexual on paper but—by the time we get to the set—I don't feel we have to film it that way anymore. I change my mind.

Guillén: And what kind of a time period are we talking about?

Tan: A year and a half. Alessandro came in about halfway through. He kept on giving me so many notes that I kept incorporating into the script that at one point I decided he should accept billing as a co-writer because he was so involved in the script's development.

Guillén: Had you cast him as Andrea yet?

Tan: Not really. Maybe subconsciously I was thinking about casting him; but, I wasn't firm about it. He had no acting experience and he was in Italy. The whole thing didn't gel in my head. Finally, at one point I just asked him.

Calza: It was in June, about two years into the project, about a year after he started talking to me about the movie, just before he started shooting, that he asked me if I wanted to audition and the way we went about it was original, it was all "new media." I auditioned through videotapes I made about my personal life and—once he cast me—we rehearsed through Skype, with him in Dallas, me in Genoa, and Adam Neal Smith in Los Angeles.

Tan: I would send him a couple of pages from some of the scenes, he would videotape himself, send me the clips, and then I'd look at the clips and tell him what I thought. The first time he sent me the clips, he was so nervous that he didn't open my email notes back to him until about a half an hour after he received them.

Guillén: With Ciao having this international profile—you in Texas, Adam in California, Alessandro in Italy—do you consider Ciao a Texan film? Is the film scene in Dallas much different than that in Austin? Does Ciao reflect film culture out of Dallas?

Tan: The Dallas film scene and the Austin film scene are significantly different in the sense that—even though there are a lot of independent films being made in both cities—the Dallas sensibility is oriented towards making the Hollywood calling card. They do a lot of high concept pieces with low budgets—a lot of genre films are made in Dallas—whereas in Austin they just make the films they want to make and they end up being the films that get into the big film festivals.

Guillén: Doesn't that tell you something?

Tan: It does. It's weird. I've always identified more with the Austin scene than the Dallas scene. At the same time—as much as I don't want to brand Ciao as a "Texan film"—after watching it so many times, I recognize it's a very Texan film, but by an approach that hasn't been used by a lot of Texans, if that makes any sense. There's a tendency with a lot of Texan filmmakers when people shoot films in Texas about Texans to make them colloquial. I don't think I did that in Ciao.

Guillén: If anything, you avoid that hazard by having a sense of humor about it, especially in the scene where Andrea, Jeff and his half-sister Lauren are playing the guessing game about the foreign languages and Jeff uses Texan slang as his foreign language. There's a loveliness in that.

Tan: But then someone told me that I'm still not a local because I've only lived in Texas for 10 years. I'm still taking everything in as an outsider.

Guillén: How did David Lowery become your co-producer and editor? Is the Dallas film scene so tight that such collaborations are inevitable?

Tan: Pretty much, yeah. I met David about eight years ago when we were both just experimenting with short films. He and his friends, the group of us, pretty much help each other out with our films. We've grown together in our appreciation of cinema and how our sensibilities have progressed over time. It's nice that we also like the same kind of films, which is not the case—we've discovered—with a lot of other Dallas filmmakers.

Guillén: Ciao's overall design is striking. The compositions are frontal, photographic. The camera is still and steady. As a designer, Alessandro, did you have much to do with the look of the film?

Calza: No, not really. That's Yen. That's Asian in general. Usually Asian style is very much about simple things. Sometimes they can do stylish things with just paper. It sounds stupid but they can come up with very strong ideas, even if they don't have huge production budgets. Yen is very good at exploiting whatever he has.

Guillén: Your design skills didn't come into play at all?

Calza: No, not at all.

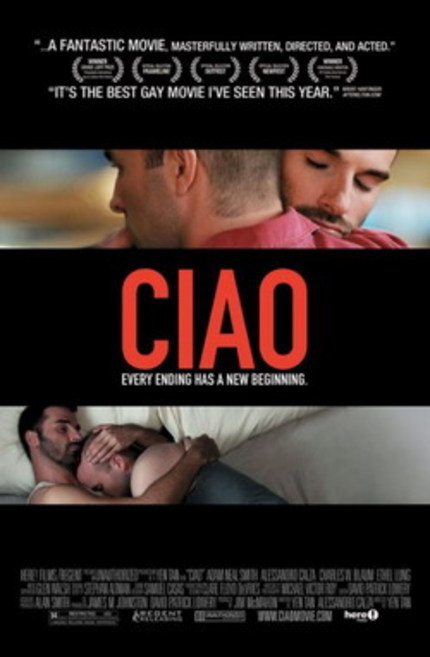

Guillén: Not even with designing the film's posters?

Calza: Yes, those I designed.

Guillén: I wanted to highlight what I felt was an interesting substitution pattern in the poster design. There were two posters that I saw. One had the three faces of you, Adam and the actor playing Mark. And then there was the other one with you and Adam and the tree between you. In my mind, you equated the tree between you with Mark, the absent figure.

Tan: That's an interesting observation.

Guillén: What made you choose that one shot of the sidewalk leading to the tree?

Tan: I'll add something to the whole design element. This is another example where Alessandro and I really stimulate each other when it comes to these kind of ideas. As a result of knowing Alessandro, I became more design-conscious. He would express his views and show me what he liked and, therefore, it generated a new sense of awareness when I would see what he had to show me and listen to what he had to tell me. The same thing happened when I introduced him to films he had never seen. He would watch them and say, "Oh, I see what you're saying." It was a mutual learning experience for both of us.

As for the poster, we had a lot of discussions about it. We ran into problems where we were trying to figure out whether we should market Ciao as a gay film and draw in gay audiences to watch the film? The poster with the three faces was an attempt to get people to come in and watch these guys. The version with the tree was more the artistic version; but, I don't think it's very commercial. I don't think people would "get" that poster.

Guillén: That isn't the one you're using?

Tan: Not really. We go back and forth.

Guillén: Use the tree one. Trust me.

Tan: You think it makes more sense?

Guillén: It underscores the integrity of the film.

Tan: The funny thing about the tree in that scene: that location came about because we didn't have the alternate location. The way it was originally scripted, Mark is exiting the hallway of his apartment building. It's an interior shot. But we couldn't find a hallway that was long enough for me to shoot as wide as I wanted to. We were a week and a half into the shooting and still hadn't shot any of these hallway scenes. Finally, I was sitting just outside the door of the complex that I live in and we had rented out a complex right next door where we were shooting a series of scenes. As I was sitting there, and I saw the sidewalk leading away through the buildings and the tree, it clicked. I thought, "Oh, this makes sense." The person walking out of the unit, walking down the sidewalk to where his car is parked and it's parked beneath the tree. I also like the idea of playing with offscreen space. So I thought, "This works. It totally works." And it was outdoors and there was a tree, which had a sense of life to it.

Guillén: The Greeks, in fact, have a term called endendros—"the life at work in a tree"—which is often a mythic referent between the realms of life and death. I concede that's probably not anything you were even thinking of, but, it's what I see. And it's universal. And that's why—of the two designs—I would recommend the image with the tree at the center. For me it has a stronger thematic thrust; an image that will survive over time.

Calza: We actually have, like, 30 other designs.

Guillén: In gist, I'm trying to emphasize your fine sense of design. Your website's interactive presentation is notable. Can you speak a little bit about your design background?

Calza: Ciao as a movie came to me not because I specifically wanted to act. I never had that ambition. I never pursued acting. But at the end of the '90s, when I started to get onto the Internet, I decided that it would be interesting to use the new media to expand personal visibility. By that I mean I wanted to make myself known to other people everywhere for no reason. With traditional media you are famous for a reason. My idea was to completely co-opt that rationale and approach from the opposite angle. I wanted to be known for no reason. I started out with photographs influenced by artists like Cindy Sherman or Matthew Barney. I wanted to use photos of myself to create a website that would seem like the website of a famous person. That was the personal level.

At a more political level, and from a gay perspective, I wanted to show everybody that—with just a little money—a person could achieve a visibility that had previously been reserved for celebrities with a lot of money. If I say so myself, my website is better than Madonna's! I actually joke that I was 2.0 before 2000. In 1999 I started with a website that had information about me and the music that I liked, way before MySpace. Now everybody has a personal website. But I remember at the time that I created mine that people thought it was weird that I wanted to have my own personal website. Now everybody's doing it. I'm actually thinking about 3.0 right now. Initially I was a graphic designer, then I shifted into web design, I used photography, I used video and I used myself—not because I was self-obsessed—but because it was the most convenient asset at hand. I could take pictures of myself. I created my web persona. Ciao became a larger step of that whole progression: I've got a personal webpage, I'm doing video, and now I'm doing a movie. I want to see how I can use the whole of this work as viral marketing for the movie itself. The result is that I know more people in San Francisco than I do back home in Genoa. I know like 200-300 people in San Francisco and probably a few thousand people are aware of me and my work here in San Francisco, even though they don't really know who I am.

Guillén: Cultivated web personas are the natural result of 2.0 and they do harbor a global potential that can be both rewarding and addictive. I keep wondering what will happen when they pull the plug? Let's talk about some narrative particulars in Ciao. I liked that Jeff's step-sister Lauren was Chinese. That was an unexpected and intriguing touch. Where did that come from?

Tan: People tell me that often. It came from the conscious decision to make a film with people I knew already. I've known Ethel Lung who plays Lauren for years. She was in my first film. Adam is also someone I've known for a while. I felt I knew Alessandro sufficiently from interacting online. I wanted to create an environment where I wasn't directing actors I'd just met. I wanted to work with people I knew personally so that I could add some of their personal traits into the onscreen characterizations. Adam and Ethel have been good friends for a long time and they've always had this kind of sibling rapport going on between them that I felt was interesting. For the story, I needed them to be siblings so I worked it out so that it would make sense; but, I also didn't want to make a big deal out of it. I wanted it to be casual. Jeff's mom divorced her first husband and married a Chinese guy who had a daughter. That's it.

Guillén: Simple, yet multicultural and effective. Were there discussions about what the nature of the relationship was going to be between Jeff and Andrea? There was a sense that they might fall in love and the whole narrative would have a happy ending; but, that would have been too predictable and I didn't want that to happen. Still, it came very close. Alessandro, can you talk about what—as your character Andrea—you were doing for Jeff in that bedroom scene? What was your sense of their affection?

Calza: For me, my acting approach in the movie was quite mixed from Adam's. I wanted it to be more than just acting. I pushed for that a lot in the relationship between me and Adam so we could break down professional distance. It wasn't that I was cruising him for an actual relationship; but, I wanted our interaction to develop intimately. Adam is a charming person but he's more closed off about his feelings. When we got to that scene, for me it was liberating because it was the first time I could be close to Adam, the way I wanted to be. I think it was the last scene we acted together and it's my favorite in the film, not just because it's sexual; but, because it was the only chance to be close to him as a person, not just acting.

Guillén: And yet, within character, you struck me as the reserved one or the one who had less need. When he leaned in to kiss you, you backed up a bit to look at him. It gave the sense that you were the strong one who could contain his need. You gave him what you needed; ballast for his grief.

Calza: There was a mixture going on. On one hand, there was what we had to do, what Yen wanted to have happen and what he expected us to act. At the same time, for me, I didn't know what was going to happen.

Tan: On that note, me neither! [Laughter.]

Guillén: They're both so handsome that the audience holds its breath expectantly.

Calza: It was the last scene that we shot because nobody knew what was going to happen.

Guillén: Ordinarily, because of its emotional difficulty, I would imagine that would be one of the first scenes you would film to get it out of the way.

Tan: In case the actors fight and don't like each other. But then I also took a while to figure out what I wanted from that scene. In the script that scene is only two sentences. They kiss and then they hold each other, that's it. It wasn't a scene that was heavily blocked out. It turned out to be a four-minute one-take shot.

Guillén: It reads as authentic and real in a subtle, distinct way. There's not a sense of it being passion as much as it is the sweetness of shared grief. The moment didn't collapse or capsize into the expected.

Calza: We shot on a closed set. We had given much thought to being comfortable—not so much for me as much as for Adam—and it was the final wrap-up scene so I felt that me and Adam told each other through that scene a lot about the conflict we had as actors on the set and the tension between us. I wanted to make the movie in a more personal way.

Guillén: Was Adam afraid of you?

Calza: He's a more reserved person. He approaches acting in a more professional manner. For me it was more an experience.

Tan: In retrospect, it worked for the characters. Jeff, Adam's character, was more reserved and closed-off. In that scene he just lets it go. And that actually kind of happened when we shot that scene. The kissing scene was a letting go. Every time I watch that scene, I see something different from Adam, little gestures and movements.

Guillén: How I read the surrender of that scene was that it expressed the gift men have to be nurturing for one another—and I mean the male nurturance that is unique to their gender—where feelings are contained within the moment, gathered, and then let go. Your character, Alessandro, actually didn't express much emotion until the final scene in the airport. In that moment is when the audience realizes how much Andrea has given Jeff; but, also, how much Andrea has lost by never meeting Mark, how much he was expecting and how he felt he had found the person he was looking to love only to have it be taken away on the eve of its fulfillment. That sense of frustrated anticipation was palpable and heartfelt and—I felt—very true to gay male experience.

I commend you both for how carefully observed the film is, how it holds silence, how subtle it is. "Slow" is a lazy way to describe it. The measure of its cadence is specific. That being said, you obviously decided not to make Ciao a Hollywood calling card? So what are you expecting from the film?

Tan: It's been so hard for us to get any press attention for this film. Obviously, because we're doing it on such a low budget, I have to be my own publicist on the film; but, trying to get people to pay attention to it has been nearly impossible, which is why I'm so grateful for your coverage. As far as knowing what to expect from the film, I don't want to stress myself out about what's going to happen—whether it will be accepted, whether I get to do another film, whether it will impact my career—it's more like just wanting to appreciate all the moments we have had in making the film and the moments we will have as we go forward, interacting with audiences, which is what we've been gaining so far. We talk to people after the screenings in the lobby where they're waiting to talk to us and they step up to us and that's already great. Q&As right after the film are difficult because the movie ends on an emotional high note and people need time to appreciate it. At almost every screening when the film ends, there's this sense of being touched and in the moment.

Guillén: Are there any plans to continue the story? To bring Andrea back to Jeff?

Tan: We talked about that and considered setting the sequel in Italy. But that would be more expensive now with the failing economy. No, there's no sequel in the works. We want to do another film together but it will be a completely different story.

Guillén: I hope you take that question as a compliment because the audience has become so invested in the characters. I got the sense they would keep in touch. As a hypothetical, what do you think happens to Jeff and Andrea, Alessandro?

Calza: If I think of it in my terms, yes, Andrea would return to Italy, think it over, and then invite Jeff over to give it a chance. Especially after the kiss, I think Andrea realizes there is something between them.

Guillén: Shared grief can create relationships. When I lost my partner of 12 years to AIDS, I was struck by the fact that people I thought were going to help me, weren't there to help me and complete strangers stepped in and did all they could. The stories of those relationships are rarely told. In my own wishful thinking, I would want a sequel just because such relationships are rarely represented. Realistically it might be doubtful that Jeff and Andrea would become lovers; but, whether or not they become lovers is not as important as the depth of their interaction. Perhaps they would merely strengthen their loving friendship with the memory of this man shared between them?

Calza: Probably, yes. After the kiss, I imagine Andrea would be even more drawn to Jeff, if only for consolation and not sex. Developing such an emotional connection in such a brief time would make me want to explore the whole relationship further. But, of course, such an intense encounter doesn't lead to a happy ending where Andrea decides to return to Jeff; that would be false.

Tan: Interestingly, a lot of people told us they thought that's how the story was going to end up. They thought Andrea would stay and not return to Italy, which was not a development we ever considered.

Guillén: As a filmmaker, I would encourage you to continue capsizing such expectations. Such facile audience expectations need to be collapsed. The authenticity of the film is precisely what surprised me.

Tan: Originally, the ending of the film was when the garage door closed on Mark. I thought that was the perfect place to end the film. But then David Lowery convinced me we could create an epilogue which would appear to tie everything together though through a hint of ambiguity.

Guillén: I very much appreciated the closing shot where you show Jeff riding Mark's motorcycle because it expresses how an individual incorporates someone they've lost. Death truly is the middle of a long life, as the Irish say, it's not the end. It's a bridge that leads to the future. In the few years after my partner passed, I found myself incorporating him through small gestures like coiling the garden hose or cleaning out the roof gutters. I found myself wondering how that happened? It happens through love and memory. You become what you do not want to lose and achieve that becoming by incorporating their familiar behavior. For me that is the true religiosity of memory.

Tan: When we pieced the final shots of the film after the garage door closes, it was a perfect way of bringing the opening shots back into the film. The two opening shots are the two closing shots. The framing device is a ring. I wanted the audience to invest the negative space with accrued meaning. And that was definitely David pushing me creatively.

Guillén: To wrap up, what's coming up for the two of you?

Tan: Our next project will be called Croon.

Calza: It's comparable to Ciao in that it's a film about two men. We're still in the exploratory process. Aside from the issues of grief presented in Ciao, Ciao was likewise about looking for something far away that mirrors expectations, about looking for something that you can't find close at home so you turn to the Internet, through an exotic fantasy. Croon is the opposite. It's a story about how—even if you're looking for something exotic somewhere else and have a specific fantasy of who your partner should be—in the end, love at first sight is the real thing. You can't define it. You can't write it down. You can't control it. You can't say, "I want a Latino, I want a Cuban, I want someone my age." In the end, love is a magic you can't know until you are drawn into the experience.

Tan: Croon continues on the path of pushing ourselves creatively. Its narrative is more loose than Ciao's. We purposely don't want to script everything out. We hope to capture the spontaneous experience of two men falling in love. We hope it will trigger audiences to remember what it was like when they first fell in love. You know how sometimes you experience a one-nighter where it's not just sex? Where it feels perfect?

Guillén: I call that illo tempore.

Tan: What do you mean by that?

Guillén: It means returning to the original place, the original time. The first place. The first time. As in returning to the garden. It can happen in a one-night stand. It can happen in a 20-year relationship. It's perfection measured as authenticity. Which recalls me to a conversation I had with Apichatpong Weerasethakul wherein I asked him if he was consciously trying to create gay relationships in his films and he answered that, more accurately, he was commenting upon the Western conception of finding a relationship as if it's the end to a goal, when in truth love is destiny. You don't make it happen. You recognize it. Generally speaking, Westerners look and look and look for relationship whereas Easterners recognize they are constantly in relationship and that recognition is how you honor relationship. This is, in fact, one of my critiques of Western gay culture, which caters to fantasies more than realities. We're taught in gay culture to think, "That guy isn't goodlooking enough, he isn't sexy enough, he isn't buffed enough, he's not wearing the right clothes, he's not making enough money. I better let him go and find the right one." Truthfully, within Western culture, that's not exclusively a gay phenomenon; but, arguably, the nascent phases of gay liberation encouraged exploration over commitment. Nowadays there's more of a focus on commitment and marriage, what have you, but when I was growing up the hunt was frequently more important than the catch. Which was unfortunate only in that we weren't appreciative of illo tempore. We walked away from perfect chances for authentic relationship because we didn't take time to recognize them, distracted by fantasy's desire. We exiled ourselves from the garden. When you fall in love it's always a return to the first time in the garden. When can we expect Croon?

Tan: Oh gosh. Three years? [Laughter.] Or something! I don't know. We want to do it fast. We don't want to drag it out too much.

Guillén: Will you film in Texas?

Tan: We're actually considering filming in California, near L.A.

Guillén: Not San Francisco?

Calza: No. It's too pretty here. Too distracting.

Guillén: I could show you some ugly places. [Laughter.]

Calza: We wanted to work with the juxtaposition between New York and Los Angeles. As an Italian, these are the two cities I think of when I think of the United States. Both cities are so huge, so populated, and yet allow you to be anonymous and alone. There's a scene in Alan Parker's Fame where a character is singing alone in his apartment, which is at the same time located in Times Square. That feeling of emptiness and being alone is heightened by the metropolitan feel of cities like New York and Los Angeles. Memphis doesn't have that. Even if you're alone in Memphis, it doesn't have the same quality as being alone in New York or Los Angeles. Similarly, in San Francisco there's always a sense of community around you.

Guillén: Well, if you ever decide to film in San Francisco, can I be an extra in the background, some gay guy walking two pomeranians while fluffing up my hair?

Tan: [Laughs.] Sure!

Cross-published on The Evening Class.