Review: Criterion Presents Three Films by Mai Zetterling

This triptych from the late Swedish actress-turned-auteur boldly takes on reproductive issues, suppressed trauma, sex, and more.

Confrontational and bold, the directorial work of successful actress-turned-filmmaker Mai Zetterling exhibits an almost meta grab of her own career. Once relegated to starring in male-driven flights of fancy and whatnot, the eventual Swedish expatriate opted in the 1950s to make her way behind the camera, essentially seizing control of her narrative. In so doing, Zetterling moved the needle a small way forward, thus cultivating inroads for the female perspective amid the biggest and longest surge of World Cinema that regularly challenged and engaged audiences. While the ripples were big for this smart and vibrant scene, it was also tremendously male-dominated.

Following a go with documentary filmmaking beginning in the 1950s, Zetterling moved on to narratives. Looking to go big, she arranged to adapt no less than Agnes von Krusenstjerna’s waves-making seven-novel-cycle of her “Miss von Pahlen” series, known as “Fröknarna von Pahlen”, which ran from 1930 to 1935. The onscreen result is Loving Couples (Älskande par), a pre-World War I period piece of surprising scope for the Swedish film industry.

The title, “Loving Couples”, is of course ironic- something that no doubt stung more in 1964 than now, when its irony is likely assumed. The film depicts the separate plights of three women about to give birth in a particularly impersonal maternity hospital. Ingmar Bergman aficionados will recognize many of the names in the credits, including the three leads Harriet Andersson, Gunnel Lindblom, and Gio Petré. Vital to the overwhelmingly austere vibe of Loving Couples is the work of the film’s cinematographer Sven Nykvist- by this time firmly established as one of world’s greatest (and also known primarily for his collaborations with Bergman).

The Criterion booklet essay on Loving Couples by Mariah Larsson discusses how Zetterling unconventionally utilizes “framing, narrative structure, editing, and camera movement in order to create a sense of the ways in which sexuality and reproduction influence women’s lives”. Indeed, there’s much to admire about Loving Couples as a first narrative feature and otherwise. Yet, the film never quite impacted me as it does others. I largely dismiss that this is due to its heavily female perspective, as that isn’t an issue with numerous other films directed by women about women living the lives of women. Rather, Loving Couples is a cagily interior piece, told in a blatant fugue state, bordering on fevered at times. It is a film that, upon this initial viewing, I appreciate for its boldness in perspective, its brave performances, and its tight craftsmanship- but still I fail to connect with.

1966’s Night Games (Nattlek) finds Zetterling in evermore daring territory as she adapts her own brazen novel for the screen. The story takes us into a once-ornate but now foreboding large home of man-and-wife-to-be, Jan (Keve Hjelm) and Mariana (Lena Brundin). Through increasingly innovative cross-cutting and well-devised practical transitions, flashbacks to Jan’s lonely youth materialize. The cascade of repressed drama plays out with the striking face of young Jörgen Lindström, most recognizable for his cryptic presence in Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence (1963) and Persona (1966). Here, though, Lindström basically carries the film. The biggest name on screen, Ingrid Thulin, plays vulnerable young Jan’s flighty, obsessive mother.

Though Night Games rode a strong wave of daring international films out of Sweden and elsewhere, it found itself the recipient of specific controversy. No less than former child luminary Shirley Temple denounced it as “pornography for profit” (as though most other pornography is the result of philanthropy?). Perhaps Ms. Temple’s own lived experience as a major child star, particularly one who’s characters pranced around in too-short dresses to cheer up cranky old men, had caught up with her. In Night Games, it does feel at times that there’s no taboo that Zetterling won’t take on. In one notorious scene, Thulin’s invasive matriarch catches her naked son masturbating in bed. She shames him something fierce; this following her inappropriate taunting of his penis only moments earlier.

If Hjelm’s performance is too somnambulistic for the film, Thulin, Brundin, and Lindström find the proper register. For me, it all checks out as it ought. It’s thoroughly reasonable for Jan to find himself awash in memories and feelings long left to these long-abandoned walls.

Night Games caused an uproar when it was deemed too racy for the commoners at that year’s Venice Film Festival, but shown to the jury. It seems the press interpreted the general public’s insulted reaction as yet more anger towards the film itself. And so, Night Games got labeled “controversial”. If frank looks at sexuality and sexual rejection as well as gross materialism (as spotlighted in the finale) are “controversial”, then yes- Night Games crosses precious lines for 1966.

The third and final film in Criterion’s Zetterling set is perhaps her most well-known, 1968’s The Girls (Flickorna). In the globally resonant time “make love, not war”, Liz (Bibi Andersson), Marianne (Harriet Andersson), and Gunilla (Gunnel Lindblom) are gonna put on a show. The times may be a-changin’ in this age of Aquarius and whatnot, but in Zetterling’s firmly grownup world, tensions play out more in the bedroom than on the streets. Which brings us back to the show the ladies are producing, the 411 BC play Lysistrata by Aristophanes.

Known for its early satirical dissection of male/female sexual dynamics in a self-antagonizing Ancient Greece, Lysistrata’s central premise has never not been potent. In it, the women of the country’s warring factions team up to block their men from sex until they stop their fighting. (I asked this when Spike Lee appropriated the concept for his 2015 film Chiraq, and I’ll ask it now: Wouldn’t this tactic just make most of the men more frustrated and angry?) In 1968 Sweden, however, Lysistrata’s potency emerges in a different way, as the play often finds itself under the microscope.

And, more power to Mai Zetterling for drudging up Lysistrata only to have it become a prime subject of debate for The Girls. The filmmaker and her cast realize that Aristophanes’ once-forward thinking sharp comedy hinges on some very antiquated (to put it nicely) notions of female libido having an on/off switch, implying that for women, their only use for sex is to appease their man. As for the men, they’re notion but festering hardboiled aggression bombs just waiting for the next opportunity to spear an enemy in the face. (Okay, maybe that characterization isn’t so off for a lot of guys). There’s a gender distilling inherent to it that even in 1968, felt absurd in unintended ways.

Zetterling, utilizing her by-now carefully honed dynamic editing style and the versitility of her talented, well-known stars, deconstructs Lysistrata’s deconstruction, and then takes it even further, deconstructing her own deconstruction. It’s a bold approach that paid off, as The Girls has gone on to be recognized by many as one of the greatest Swedish films ever made. While I agree that it absolutely is an admirable piece, upon this introductory viewing, I personally found it inferior to Night Games. The Girls, in all of its externalized pontifications, feels, by comparison, ever so removed from the core humanity it’s most interested in. That said, all three leads grapple with very separate yet very relatable issues affecting women at the time. (Career versus family; ineffectual husbands; being the default child caretaker, and more).

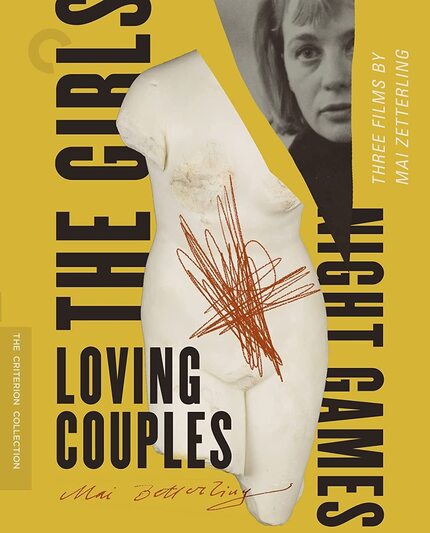

Back in the day, Criterion would’ve released these films with each in its own case and collected into a slip-box of some sort. Those days may well be gone, as Three Films by Mai Zetterling (and the subsequently released Michael Haneke: Trilogy) are simply the thickness of single-film releases, albeit with three discs and a folded insert housed inside. While this no-frills packaging feels like (and likely is) indicative of cost-cutting realities befalling the company, it also works. The humble footprint somehow compliments the films, and let’s face it, while collectors are drawn to big thick bells-and-whistles prestige packaging, shelf space can be a real issue. And if the physical girth of this set isn’t a throwback to Criterion’s earlier days, the stark yellow/beige/grey design work certainly is. While old Criterion DVD covers have a way of often looking tacky and cheap, the Zetterling set brings it back in a tasteful and even commanding way.

Criterion has a long history of making monochrome Swedish classics pop on home video, and the contents of this Mai Zetterling collection are no exception. Criterion presents all three of the films with new 2K digital restorations and uncompressed monaural soundtracks. All three features boast a perceived silvery accent amid their clear-as-crystal dreamlike aesthetic. With the fine effort that’s gone in, including new English language subtitle translations, the term “classy” can’t help but come to mind.

The bonus features, while not voluminous, are definitely sufficient. On the first disc, accompanying Loving Couples, we find author Alicia Malone vibrantly pontificating about the significance and vitality of Mai Zetterling as a director. That’s the only newly produced supplement; from there, we have only archival material. As far as archival material goes, however, this is essential Zetterling-related content.

The forthright 1989 documentary Maybe I Really Am a Sorceress focuses on the remote, nature-driven private life of director Mai Zetterling, cross-cutting discussion of her films. In it, we learn firsthand of her witchy and supernatural beliefs, as well as her “pre-feminism feminist” views. The piece features interviews with Zetterling; her co-screenwriter, David Hughes; and actors Harriet Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Bibi Andersson, and Gunnel Lindblom. Not all of them have nice things to say about working with the filmmaker. “She was a witch, and quite mad…”

Less barbed, likely for its posthumous status, is the feature-length 1996 documentary Lines from the Heart. Director Christina Olofson captures a reunion of The Girls actors Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, and Gunnel Lindblom at Zetterling’s now-abandoned rural home. The trio abstain from too much criticism this time, as not to speak ill of the dead. The gathering initially comes off as more contrived than anything else, as Bibi Andersson is seen running late (there’s a cameraperson in her car, filming her drive there) while the other two wonder where the heck she is. Their subsequent conversations are a lot more organic, as they discuss not only Zetterling (politically, she was “a socialist who didn’t use the vocabulary”) and The Girls but also their own careers, including another mutual director for all of them, Ingmar Bergman. Though Lines from the Heart is flawed, it would’ve been wrong for Criterion to not include it in this set.

Finally, we have a 1984 interview with Zetterling on Loving Couples and The Girls, as well as Swedish television footage from 1966, filmed on location during the production of Night Games and at the film’s premiere. The printed essay that is enclosed features a fine essay by film scholar Mariah Larsson.

In a time when it was a particularly wild notion that a glamorous actress of Hollywood and England could transition into directing in her home country, Mai Zetterling defied the odds. She didn’t simply re-emerge as a director, but as a full-blown auteur filmmaker. Criterion’s Three Films by Mai Zetterling does an excellent job of not just showcasing the titles in question, but of ushering further into the cinema canon. Audacious and artistically daring, Zetterling’s work continues to rightly mystify, enchant, and resonate around the world. As one onboard documentary summarized her, she was “a queen of the night and a master of the light; a wise woman, conscious of being part of the harmony of the cosmos. Maybe she is a sorceress after all.”

Loving Couples

Director(s)

- Mai Zetterling

Writer(s)

- Agnes von Krusenstjerna

- Mai Zetterling

- David Hughes

Cast

- Harriet Andersson

- Gunnel Lindblom

- Gio Petré

Night Games

Director(s)

- Mai Zetterling

Writer(s)

- David Hughes

- Mai Zetterling

Cast

- Ingrid Thulin

- Keve Hjelm

- Lena Brundin

The Girls

Director(s)

- Mai Zetterling

Writer(s)

- Mai Zetterling

- David Hughes

- Aristophanes

Cast

- Bibi Andersson

- Harriet Andersson

- Gunnel Lindblom