Sundance 2018 Review: SWEET COUNTRY, a Powerful Slowburn on Australia's Not-So-Sweet History

Warwick Thornton's Sweet Country opens with Sam Neill's preacher Fred Smith sharing a meal with his Aboriginal farmhands Sam and Lizzie Kelly (exceptional newcomers Hamilton Morris and Natassia Gorey-Furber). "We're all equal in the eyes of the Lord," the preacher sermonizes as he says grace with the couple.

This scene serves as a fitting yet ironic prelude to this slow-burning tale on the volatile race relations in 1929 Australia. Rife within these lands are normalized racial tension and double standards, evident in how white outlaws are cheered upon and mythologized on-screen while an indigenous man guilty of only shooting someone in self-defense is clamored to be hung under the rule of law.

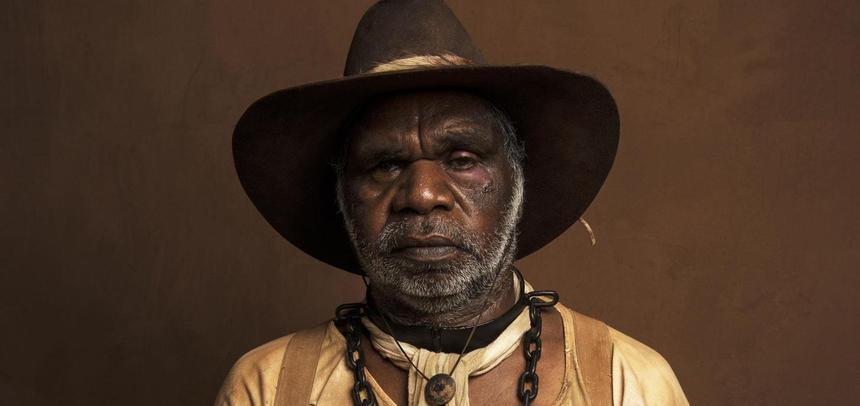

Based on real accounts, Sweet Country tells the story of Aboriginal stockman Sam Kelly who finds himself on the run and being pursued by a search party after he kills the farm-owner he was loaned out to.

The man Sam shot, Harry March (Ewen Leslie), was a veteran who just recently became in charge of a farm. There's a bit of commentary here in how the film uses March, a newcomer to town, to illustrate the inherent bias a white man can be granted because of his skin. March is automatically assumed as the victim by many even without contextualization.

In reality, March is a violent man who drowns his war trauma with alcohol and by abusing the help around him.

In a scene shot in complete darkness, March rapes Sam's wife, Lizzie. Effective without being graphic, the sequence leaves the entirety of the crime to the audience's imagination. They are left only with the quieted whimpers of Lizzie as she is threatened by March just to take it, or else she and Sam will be "skinned alive." How deliberately the scene plays out, with these sparse yet sharp elements, creates a potent moment in the film — one that is felt in the entirety of its runtime.

This rape though doesn't serve as the catalyst for Sam to kill March, but that of the escape of Philomac (played by twins Tremayne and Trevon Doolan), an adolescent half-caste farmhand March also borrows from a neighbor.

In search of this young man he chained overnight, March charges guns-blazing into Sam's abode. Akin to quick-draw battles from the wild west, Sam shoots March split-seconds before he finds himself in the path of the veteran's erratic shots.

As archetypal as the story sounds, the film's characterizations create a compelling and complex narrative on Australia's racial divide.

March, though racist, abusive, and homicidal, is given a backstory nuanced by PTSD. Though this doesn't render his actions excusable, this puts a reason behind his brutality.

Philomac serves as an interesting character as well, as even if he unwittingly sparks the film's conflict; he becomes a symbol of the cultural takeover colonization brings about. He longs to escape even if it means becoming more and more like the white man. His adolescent desires gain a layer too through the reveal that he is the illegitimate son of the farmer is working for.

There's also Archie, another stockman who works the same fields as Philomac, who starts off as an acquiesced slave but becomes a character of weary apathy and resignation.

Without giving away details, these complexities in Sweet Country's characters — ones that pop up in the most unexpected of times — are what audiences should look out for.

The same unpredictability is built upon by one of Sweet Country's most ingenious devices, the use of flashbacks/flash-forwards.The film peppers its typically linear and slow-burning narrative with bursts of vignettes that lend an element of fatalism to the film. You may see character deaths right after being introduced to them and be left wondering how it would come about. The flashes may also mislead and turn 180 degrees in their meaning once already in its proper place.

The environment also serves a vital element in the storytelling of this western-slash-slave-drama. Sweet Country's cinematography presents both a beautiful yet harsh locale. One both with grandeur and unrefined.

The effect of this presentation, coupled with the film's sparse use of music, produces an intimate experience. In the moments where the camera is focused on Sam, you can't help be engrossed at the moment created by this convergence of impeccable technicals and a stirring yet restraint performance.

The reality in Sweet Country is anything but sweet. Instead, the title paints an ironic picture. That of a beautiful country becoming a stranger to its native people, a land once of milk and honey whose "sweetness" is slowly becoming one that exists only in memory.