Psycho Pompous: Expressionist Horror, Part I: The Man Who Laughs, An Introduction

The most triumphed example of horror film expressionism is the 1920 feature The Cabinet of Dr. Calagari by Robert Wiene, which set the foundation from which all successive expressionist films and horror films of the 1920s would rise. Though the catalogue of expressionist works would number less than thirty throughout the movement’s existence, it had a profound and immediate impact on the world of cinematic storytelling. Many critics and audiences would agree the most important films of the expressionist era besides Calagari would be Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, both released in 1927. Though those two films are seminal works of filmmaking and objectively two of the greatest films ever created, their release and subsequent stardom overshadowed possibly the most important horror film of late expressionism that exists, which was released the following year: The Man Who Laughs.

This work would be constructed by a director of supreme merit and visionary craft: Paul Leni. Leni had made a name for himself in Germany early-on as a competent yet avant-garde art director for Ernst Lubitsch, Joe May and E. A. Dupont. As his repertoire and reputation grew, so did his desire to craft his own filmic vision. Leni would be put in a position of power at the Projektions-AG Union, which was originally designed to be a German-only production company to compete against foreign films in their home market, but would eventually be regulated to produce propaganda films at the behest of the Weimar Republic (and eventually the Nazis, when merged into UFA GmbH, and then bought by Alfred Hugenberg in 1927). The first major effort of this transition was in Leni helming the German-Polish propaganda film Das Tagebuch des Dr. Hart in 1917. It was a nation-wide success, touting a new director with a unique vision had entered the landscape. Upon this wave of acclaim, Leni would helm The Mystery of Bangalore (1918) with Hungarian-born German director Alexander Antalffy. Antalffy had been an eclectic crewman for multiple directors by this point, but also was one of the few filmmakers who realized early on the talent and drive of not only Leni, but of Bangalore’s breakout star Conrad Veidt.

Veidt was originally an aspiring stage actor who was deployed to the eastern front in World War I, but due to persistent health issues, was discharged and returned to Germany in early 1917. He was quickly discovered by producer Oskar Messter, who would come to be known as the discoverer of most of Germany’s biggest silent screen stars, and was initially cast in Robert Reinert’s Der Weg des Todes (1916) as a jilted ex-lover of the protagonist (played by famed Italian actress Maria Carmi), and his performance started a rippling effect through the industry as someone for which directors should pay attention. He gained solid credibility for his casting and performance in Robert Wiene’s 1917 feature Fear, though he was still overlooked comparatively to his co-stars upon the work’s release, and would be in several of his subsequent projects. However, upon being approached by Leni and Antalffy, his role in The Mystery of Bangalore proved to be his most widely-lauded work to that point and thusly he became a household favorite.

However, that inclining favoritism would wain in Germany due to the scandal that arose with his inclusion as the lead actor in possibly the most divisive of director Richard Oswald’s films. To clarify, Oswald’s claim to fame is his foundation of the enlightenment film movement with sexoligist Magnus Hirschfeld. Though already a firmly established director of over fifty films by this point, Oswald’s 1919 feature Different from the Others was the first movie dealing explicitly with the subject of homosexuality, and thusly met with large public and moral scorn. Veidt was publically good friends with Oswald, and would appear in numerous other features of the director such as Around the World in 80 Days (1919), Uncanny Stories (1919), Figures of the Night (1920), Lady Hamilton (1921) and Lucrezia Borgia (1922). However, as a direct result of the Different from the Others’ release, violent clashes helmed by conservative reactionaries spurred the reintroduction of censorship in Germany. This, in time, began an unofficial blacklist of jewish and leftist filmmakers and stars who would lose most opportunities to work in Germany. Upon Joseph Goebbels’ appointment to the Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda in 1933, many (who hadn’t already fled Germany) were either placed under house arrest or were detained as political prisoners. Different from the Others was banned in 1920 (along with most of the enlightenment films), with all known copies being physically destroyed; though a single surviving copy was discovered in Ukraine in the late 1970s.

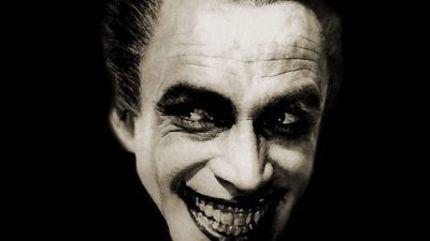

Now why is this tangent important to this discussion? Because with the reinstallation of censorship and film codes, fringe German filmmakers retaliated with the construction of cinematic expressionism, to play with the ideas normally they would be able to simply show, but now they had to be clever and inferential with their societal critiques. This is exactly what would also contribute directly to the creation of film noir in America, as a reaction to WWII and the Hayes Production Code. Veidt made a point to be at the very center of this artistic shift, as he was fervently in opposition to rising reactionary and anti-Semitic ideologies and policies in Germany (and in the following decade would come to consistently gainsay the National Socialist German Workers’ Party until his emigration to England in 1933). With his public attitude, and a clear favorite of soon-to-be prominent expressionist filmmakers, he would be cast in 1920 by Wiene in probably his most iconic role: the somnambulist Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr. Calagari. He became one of the most prominent faces of German film and horror film of the next two decades.

This then brings us back to Leni. Leni’s success after The Mystery of Bangalore was limited at best. Though he was a highly sought-after filmmaker during the early 1920s and had much clout within the German film industry; and it is beyond discussion that Leni’s artistic style was a direct and continuing influence on cinematic expressionism, the success of his own personal films had faltered. By 1924, his career had reached such a plateau that his film Waxworks was his last in Germany. It is an anthology production co-directed by famed Ukrainian playwright Leo Birinsky (though credited as assistant director) and penned by Henrik Galeen, the writer of Murnau’s Nosferatu (1920), and the co-writer/co-director of The Golem (1915) with Paul Wegener, quite possibly the first work of expressionism in movies (however as a lost film, its 1920 remake by Carl Boese and Wegener is known as the seminal expressionist telling of this golem myth). Though Waxworks is lauded now as one of Leni and Birinsky’s most intriguing works (if not one of the most disjointed ones), when it released, it was to lukewarm critical reception and commercial success, partially given to the hyperinflation and collapse of the German economy.

However, in a serendipitous twist of fate, Waxworks was brought to the attention of producer mogul Carl Laemmle as possible distribution material. Laemmle (a German-born filmmaker) had gained notoriety and fame in the American film industry early-on as a rival to Thomas Edison, starting and owning the Laemmle Film Service in Chicago. He would consolidate his many company branches and create Universal Studios in 1912. Laemmle would also rise to prominence as the first of the major American producers that would capitalize on the talent of individual actors (such as Mary Pickford and Florence Lawrence) to sell films, in effect fostering the idea of the American movie star.

Laemmle’s appreciation of Waxworks sparked an invitation to Leni to come to Hollywood and helm a feature for American audiences. Leni would uproot completely from Germany and settle in Los Angeles to make his overseas debut with an adaptation of John Willard's stage play, The Cat and the Canary (1927); he would never return to Germany. Leni’s blending of offbeat comedy and societal horror was eaten up immediately by critics and audiences alike, and solidified his name as one of the leading directors of Universal. That film is lauded as one of Leni’s best, and continues to stand to this day as the cornerstone work that beget the Universal Era of horror productions that would continue into the 1950s.

Though Universal Pictures originally set up The Man Who Laughs to be a Lon Chaney vehicle, cashing in on his fame as America’s first horror movie star, the initial production never got off the ground. It was an adaptation of the Victor Hugo novel L'Homme Qui Rit, published in 1869, with versions already brought to the screen by Pathé in 1908, and Olympic-Film in 1921. Due to lengthy rights complications with the source holders, Chaney was released from his contract, instead playing the titular character in the enormously successful The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Laemmle, intent on capitalizing this fame with his continued series of gothic epics, retooled The Man Who Laughs with Leni as director, Veidt replacing Chaney, and Mary Philbin, freshly famous off her supporting role in The Phantom of the Opera, as leading actress. Leni was given free reign to construct his crew, many of whom had worked with him on The Cat and the Canary. So much was riding on the film that by the release of it in theaters in April 1928 (it was completed in April 1927 but was held for release), Universal had pumped over a million dollars into the production budget, making it one of the most expensive American films of that era. However, the hefty investment would not pay off. With receipt totals middling and critical responses of the film being scathingly negative for the better part of the next 50 years, The Man Who Laughs would be largely buried by time. Only upon a modern re-examination of a re-mastered and re-synched version released by Universal in 2003 has the reception cooled and even turned to glowing praise, echoing my previous statements that it is one of the greatest of the silent era expressionist horrors.

As this giant preamble to the film comes to a conclusion, you may be asking why I haven’t gotten to the movie’s actual components yet. Well, as my rambling history has laid out, before getting into the actual work itself, the entire construction of the production is laden down with some of the genre’s most infectious and innovative talent of the day, with direct connections to the most well-known stars of expressionist terror. Our next part will dive headlong into the individual cinematic elements of the work and conclude beyond contest of the impact and resonance that exists within The Man Who Laughs.