Review: FYNBOS, Brilliantly Anti-Cathartic Cinema

A young white woman in high heels walks down a street in a black working-class neighborhood. Though clearly on edge, she walks with a purpose. She pauses at a row of trash cans. Clothes billow in the wind, threaded on a line nearly invisible in the bright sunlight. The sweep of the cloth calms her, helps her commit to what she is about to do. And with an anger and fear swelling up from deep within chasms of self she dumps the contents of her purse into the trash, erasing her identity with a furious hand. Next, she enters a phone booth, dials the emergency number and reports that she has been robbed.

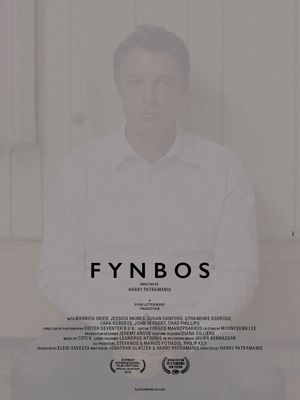

These are the first captivating moments in commercial director Harry Patramanis' feature debut Fynbos, a film as enigmatic and engaging as any Antonioni picture (early Peter Weir also comes to mind), inviting and challenging the audience to immerse themselves in the expanse of the question mark that is human nature... and humans in nature. Like the recent minimalist masterstrokes by Julia Loktev (The Loneliest Planet) and Nuri Bilge Ceylan (Once Upon A Time In Anatolia), Fynbos explores the immediacy of separateness, that startling space between couples, between classes and between races.

The title itself comes from the low-lying, ocean-like vegetation that pockmarks the vast South African estate where the film takes place. Like some alien life force or omnipotent being, the shrubby, green and yellow plants sway under the cool spring winds, always moving, always watching, yet forever fixed, alight in a pre-history, in a world modern humanity cannot even begin to fathom. How strange then to have the heavy footprint of man and woman clomp down again and again on paths only etched in the golden dream of nature and the manic nightmare of human development.

Just one day after Meryl (Jessica Haines) has discarded her identity, one day after she has lied to her husband Richard (Warrick Grier) about being robbed, she is whisked off to to this estate. Taken to a prison atop a hill, yet a prison where one can easily picture escape. Richard is a real estate developer near bankruptcy. In a last ditch effort to sell the Fynbos estate he has arranged for a meeting with a possible buyer, an old-money family from England. Anne (Susan Danford) arrives to the cape like an astronaut flying in on the wings of nostalgia, declaring fond memories of time here with her father. Her brother Lyndon (John Herbert) is not amused by this, far more ready to get back to Cape Town for a night of fun rather than a leisurely hike through the breathtaking countryside. Bringing further contrast to the proceedings is the son of the current owner, VJ (Chad Philips) and his free-spirit of a girlfriend Renee (Cara Roberts) who are staying in the guest house. We first meet Renee in a shot that echoes directly back to the nubile youthfulness of Jenny Agutter in Walkabout.

The glass house on the hill that they inhabit for the night presents itself as a strange labyrinthine stage for whatever drama is to play out. Whatever lines are to be drawn, whatever deals are to be made here in this space.

Patramanis' film remains diligently minimalist when presenting its drama and emotions. Moments that should play big pass on the breath of the wind without much notice from anyone. As Meryl tells Richard soon after they've arrived at the estate: "There's a bigger picture here and you look past it every time."

Patramanis' film remains diligently minimalist when presenting its drama and emotions. Moments that should play big pass on the breath of the wind without much notice from anyone. As Meryl tells Richard soon after they've arrived at the estate: "There's a bigger picture here and you look past it every time."

In a film full of mystery this is its most stark and striking moment; the loudest, clearest call. It is spoken by a near-passive woman in a fragile state; a woman terrified that her husband will beat her again. Soon after these words are spoken, Meryl is gone. Like a figment that was never there, the person who should have been our heroine, the one to champion, disappears into the rock formations that surround the house like a forever impending army-on-the-march. Perhaps she has formed a pact with nature itself to hide away.

The night before at the dinner table, Meryl tells of her robbery, of the poetry in her assailant's gaze, of his cool knife against her warm abdomen, the space between the ally way, and of her assailant's soft, gentle "thank you" as he leaves with her purse. Her story, these words are turning points in disguise.

Striking out across this veritable tabula rasa of a landscape, Richard searches for Meryl in a near-blind desperation. A silent madman caught up in delusions, propelled by the past, by some saintly notion of marriage and a love that was probably never there.

As Meryl remains hidden, possibly hurt, possibly dead, or just gone by her own free will, each character departs from the picture, increasingly marginalized in the frame, swallowed up or driven out by the nature around them. And yet one remains.

At first, a seemingly inconsequential figure, an outsider from the working class black township, S'Thandiwe Kgoroge's Toni, a young police officer, stands tall amidst the mysteries; a calm presence amongst the fractured ligaments of the first world that sits atop the hill. Up there is the question mark draped across the rocks, or sewn into the breeze that lilts and feathers close to the fynbos plants, the glass walls, and the searching eyes of a man who seeks some semblance of humanity, yet is perhaps too far lost to really care. For all the expanse afforded them, no one but perhaps Toni and Meryl can see beyond the outline of their own hand.

Patramanis' film has all the building blocks to be a biting political affair, a comment on the many cultural ebbs and flows and fears of South Africa. It has all the DNA strands intact to provoke, but this is not Fynbos. From each restrained performance to Dieter Deventer's breathtaking cinematography (the final shot is perhaps the most striking I can recall in recent memory), Fynbos pulses with a primal force, a force from pre-history. Yet it is understated, lulled by the wind at every turn.

As it stands Fynbos is a brilliantly anti-cathartic piece of filmmaking, full of haunted landscapes populated by haunted people. From its multinational crew, right down to its metaphors on the many kinds of barriers we put up, it is a film that also emphasizes the post-national world we now inhabit, presenting the once so-called Dark Continent as a beacon, and as a compass, to the inner frontiers we are still very much challenged by.

This review was originally published in slightly different form in January 2013 during the Slamdance Film Festival. Fynbos is now available to rent or own in the U.S. on iTunes.