"Chinese Realities/Documentary Visions" at MoMA, An Essential Film Series Tracing 25 Years Of Chinese Documentary Practice

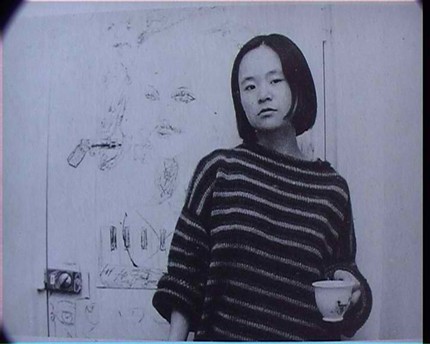

This 29-film series encompasses many forms of filmmaking: both underground and state-approved documentaries, amateur videos, web-based conceptual art, as well as fiction films that are strongly influenced by a sense of the realities of contemporary Chinese society. Some major highlights of the series are films by Wu Wenguang, a pioneer of the "New Chinese Documentary Movement," such as his 1990 film Bumming in Beijing: The Last Dreamers (pictured above) and his 2005 film Fuck Cinema.

Another must-see, well worth the considerable time investment, is Wang Bing's monumental nine-hour masterwork Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (screening May 18 and 19), his penetrating portrait of the decay and dissolution of a once-bustling industrial town. Several filmmakers and film scholars will visit for discussions. Full details can be found at MoMA's website; the series runs through June 1. Below, I will discuss several highlights of the series.

Mama, Zhang Yuan's 1990 debut feature, often acknowledged as China's first independent feature film, began its life as something very different than what it eventually ended up to be. This project began as a screenplay for a children's film entitled "The Sun Tree" by lead actress Qin Yan, based on her own experiences and inspired by a story by the writer Dai Qing; Yuan, a senior at the Beijing Film Academy at the time, was slated to be the film's cinematographer.

After a series of circumstances, including two state film studios rejecting the project, and the association with the writer Dai Qing being problematic because of his support for the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations, Zhang and his collaborators radically reworked the screenplay to more closely reflect the actual lives of people in Chinese society at that time. The resulting film was shot on a shoestring budget of about $1300, largely in Zhang's own apartment.

Mama follows a single mother, played by Qin Yan in a wonderful performance, who works as a librarian who struggles to raise her mentally disabled son without the help of her distant husband. Mama has a fascinating mixed aesthetic that would prove to be a hallmark of many subsequent Chinese documentaries and fictional features dealing with social realities. The dramatic sections featuring the mother and son are filmed in black-and-white, often with dreamy, expressionistic effects, depicting the mother's fights against insufficient social services, as well as society's discrimination against her son. The fictional story is interspersed with documentary interviews, shot on color video, with actual mothers with mentally disabled children talking about their struggles. Also, there are scenes shot on 16mm in a facility for these children.

The result is a hybrid film in which fiction and reality intertwine to create a powerful, and artful, portrait that transcends the typical "social problem" movie. Mama got minimal distribution in China; state authorities doubtless viewed this as dangerously critical of the state's handling of these social realities. (May 15, 7pm)

Hu Jie's 2007 documentary Though I Am Gone packs a powerful punch in just over an hour, as it documents a brutal early episode of Mao's Cultural Revolution. The opening images of the film are a clock and a camera lens, which recur thematically throughout, as an indication of the concerns of both the director and the subject, of capturing and recording history so that it is not forgotten in the passage of time.

That camera belongs to then 85 year-old Wang Jingyao, who used it to record the aftermath of the brutal death of his wife Bian Zhongyun, a girls' middle-school principal who suffered a savage beating at the hands of her own students in 1966, in the early days of Mao's Cultural Revolution. Bian is considered the first victim of the Cultural Revolution and its attendant purges of those considered counter-revolutionaries or enemies of the state, with the fervent Red Guards as enforcers of this policy.

Wang Jingyao is interviewed extensively throughout the film, and expresses as his credo, "I had to document the truth of history." And that he did, not only through the photographic medium, but through the physical evidence he has saved, including the blood and excrement-soiled clothes his wife was wearing, as well as her watch, which was broken at the time of the attack, forever frozen at that moment.

Director Hu Jie employs a collage-like approach, interspersing archival footage and propaganda songs with present day interviews with Wang and other survivors of this tragic period of history. The film's credits are a virtual memorial to Mao's victims, with a list of the names of many who died from the political violence Hu powerfully depicts. (May 28, 4pm; June 1, 7pm)

Jia Zhangke, in both his fictional and documentary works, has proven himself to be one of the most vital and poetic chroniclers of the rapid changes China has undergone in recent years. His 2008 feature 24 City is a fascinating hybrid of fiction and documentary, a look at 50 years of Chinese history seen from the perspective of 420 Factory in Chengdu, Sichuan province, a former military munitions plant that is about to be torn down to make way for a modern housing complex called "24 City."

The film is structured as a series of nine monologues, five spoken by actual workers in the factory, and four by actors. These actors include three wonderful actresses who give fine, sensitive performances - Jia regular and muse Zhao Tao, Joan Chen, and Lu Liping, who represent three generations of Chinese history. 24 City is a dense, complex and challenging work, encompassing in its mixture of reality and fiction physical memorabilia of the factory, a rich musical soundtrack including Chinese patriotic songs, romantic tunes, the Internationale, and Chinese opera, as well as quotes from Chinese poetry and William Butler Yeats.

Jia originally conceived of 24 City as a straightforward documentary; the work he ended up with is a much richer and melancholically beautiful work, illustrating Jia's idea that "history is always a blend of facts and imagination." (May 22, 7pm; May 29, 8pm)

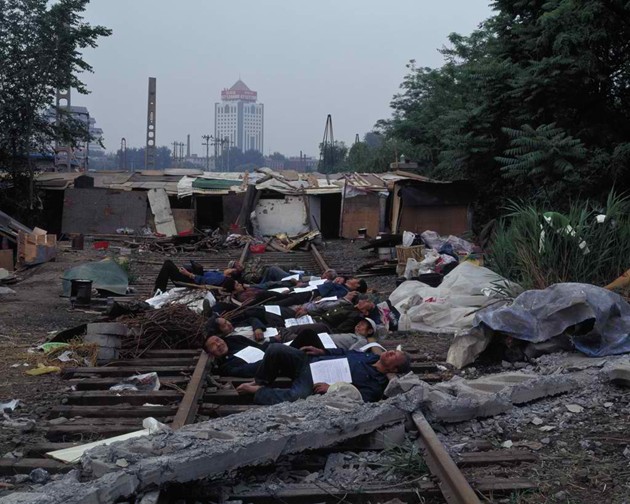

A major highlight of this series is Zhao Liang's 2009 documentary Petition, an absolute must-see, as it is an emotionally wrenching and exemplarily brave work of investigatory journalism. Beginning in 1996, Zhao filmed the stories of the "petitioners," people who come to Beijing from many provinces of China, seeking resolution for grievances that they have been unable to have resolved in their local hometowns. They set up camp in "Petition Village," a shantytown around the South Beijing Railway Station, where they dwell and sleep while making endless, and mostly fruitless, appeals at the central government petition office nearby.

Zhao's sympathetic and penetrating camera examines this situation in sometimes painful detail. Using a hidden camera to film inside the petition office, where filming is forbidden, Zhao documents the cruelly indifferent treatment of the petitioners by unseen workers behind barred windows, with security officers at the ready to forcibly remove those who become too unruly. Besides poverty and homelessness, the petitioners also face physical threats and sometimes beatings at the hands of the "retrievers," essentially hired thugs from the provinces sent to dissuade petitioners from their efforts, seen as embarrassments to local governments. Many petitioners have been trying to resolve their grievances for years on end, some stretching into decades.

The most heartrending episode of the film occurs when Zhao gets personally involved in the story concerning Qi, a middle-aged woman trying to get to the bottom of her husband's death after a work-mandated medical exam, and her daughter Juan, who dutifully accompanies her while she is petitioning. When Juan finally tires of dealing with her emotionally fragile mother - who was sent to a mental institution for a time - and wishes to escape to live her own life, she gives Zhao a note for him to give to her mother before she leaves. This leads to Qi angrily confronting the filmmaker after he breaks the news to her. This story, as uncomfortable as it is to watch, perfectly illustrates how committed Zhao is to illuminating the experiences of his subjects, people whom the government wishes to literally erase.

Petition Village was eventually torn down when the old South Beijing Railway Station was demolished to make way for a renovated, ultramodern station. However, Petition ensures that a permanent record exists of these people's stories, and that they cannot be so easily put aside. Petition will screen in two versions: a two hour international cut (which is the one I preview here), and its original five-hour version, which tells the petitioners' stories in much fuller detail. (May 25, 1pm [long version]; May 31, 4pm [two-hour cut])

Pema Tseden is a unique figure in the landscape of Chinese films, as the first significant filmmaker from Tibet, who uses non-professional casts, and makes films in the Tibetan language. He makes fictional films with strong documentary elements, and his status as an insider creating his works from within the society marks his films as quite different from most Chinese and foreign directors who have taken Tibet as their subject. Tseden doesn't give us the exoticized Tibet that many outsiders have offered; he is committed to putting on screen the real details of life in contemporary Tibetan society. His previous features The Silent Holy Stones (2005) and The Search (2009) fulfilled these aims with an assured sense of cinematic craft and a sly sense of humor.

His third and latest film Old Dog (2011), receiving a week-long run in the series, is his rawest (shot on digital as opposed to the others, which were on 35mm), and even though the humor is still evident, ultimately his most despairing. The story begins with Gonpo (Drolma Kyab), who is attempting to sell his family's nomad mastiff, a dog which is highly prized by rich Chinese. Other dogs in the neighborhood have been stolen and sold off, and Gonpo decides to sell the dog as a preemptive strike against this possibility. Gonpo eventually finds a buyer, but his furious father Akku (Lochey) sets out to retrieve the dog, and thereafter the film switches its focus from the son to the father. Akku is at his wits' end with his dissolute son, who spends his days on the couch watching TV and playing pool with his friends and his nights drinking and coming home blind drunk. Worse, Gonpo and his wife are childless, seriously endangering his wish to see a grandchild before he dies.

Old Dog shows us a Tibet far removed from the popular image of chanting monks and such; the town of the film is constantly under construction, with the assaulting sounds that accompany this. Akku and Gonpo's home often rings with the sounds of the TV blaring inane Mandarin-language home shopping and talk shows. Tseden depicts a contemporary Tibet in which traditions are slowly but surely dying out, and Akku futilely tries to fight this, leading to the rather shocking conclusion. Tseden favors long takes and uses minimal close-ups, showing us characters swallowed by the merciless landscapes. (May 15-20)

Ying Liang, one of China's finest and most incisive contemporary filmmakers, delivers one of his finest works to date with When Night Falls, his contribution to the 2012 Jeonju International Film Festival's Digital Project, in which three filmmakers are invited annually to make short films and short features that premiere at the festival and often tour afterward as a package. When Night Falls is based on the real-life murder case of Yang Jia, who was convicted of, and eventually executed for, the fatal stabbing of six police officers in a police station. This was the culmination of Yang Jia's arrest for the petty crime of riding an unlicensed bicycle and his mistreatment and beating at the hands of police. Frustrated by his fruitless attempts to sue the police, he came to the police station in Shanghai armed with knives and petrol bombs, where he ended up attacking and killing the policemen.

Ying's film is bracketed by actual photos of Yang Jia and details of the murders, but the fictionalized story within focuses on Yang's mother Wang Jingmei (played by Nai An, in a quietly commanding performance), and her efforts to support her son and assist with his defense. Ying Liang's stark compositions paint a grim picture of a legal system that is as rigidly uncaring as it is unjust, and Wang Jingmei as a woman buffeted on both sides, by the forces of activists and the implacable legal system, frustrated and exasperated with both these opposing players in her son's and her own tragedy. The power of this film is undeniable; it certainly was to the Chinese government, who harassed and threatened Ying and his family, eventually forcing his current exile to Hong Kong. (May 24, 7pm; May 26, 7pm)

For more information on these and other films in this series, visit the Museum of Modern Art's website.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.