THE HELP Review

It's not horribly offensive, like the whitewashing Mississippi Burning, but The Help has its own peculiar issues. Set in 1963 Mississippi, The Help quietly tiptoes around the more incendiary aspects of the Civil Rights era in the United States by focusing on two poor black maids and the privileged white woman who sets them free.

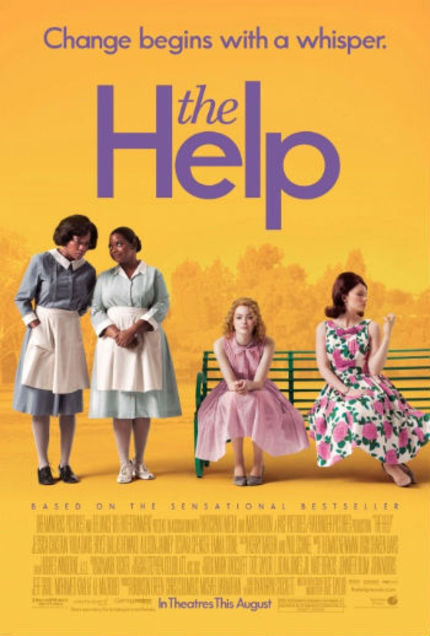

Based on a well-received 2009 novel by Kathryn Stockett, the film is well-made, with great attention to period detail, and features good performances by Viola Davis, Octavia Spencer, and Emma Stone as the true blue Southern heroines. Combined with the provocative nature of the material -- the oppression of one race by another, the courage summoned up by the weak to fight back against the strong, the unconditional love of children for maternal figures -- it makes for a potentially potent package. It moved me to tears on a couple of occasions.

My tear ducts, however, don't have any critical perspective.

The Help could also have been accurately titled Civil Rights For Dummies, though that would not convey the vital strain of bathroom humor that runs throughout the film. It is, to be sure, an unusual and very down to earth approach. After all, everyone must relieve themselves; we rarely need to talk about it.

In The Help, it's one of the precipitating factors that moves Aibileen (Viola Davis) to talk with Skeeter (Emma Stone) about the many injustices she's suffered as a maid at the hands of her white employers. Skeeter has recently returned home to Jackson after graduating from university. She quickly gets a job writing a cleaning advice column for a newspaper, but harbors an ambition to be a "real" writer. Needing the expertise of a "real" cleaning expert, she spends a little time with Aibileen, who works for Skeeter's friend Elizabeth (Ahna O'Reilly). She smells a "real" story in the off-handed comments Aibileen makes about her life, and becomes determined to write about race relations in Jackson from the perspective of maids.

For her part, Aibileen has been humiliated once again because of a bathroom. Hilly Hillbrook (Bryce Dallas Howard), the leader of the Junior League for all proper young ladies of Jackson, has reminded all her privileged white friends that black skin must never touch sacred white porcelain that has been reserved for sacred white bottoms "for fear of disease. ... We must protect our children." As a result of Hilly's proselytizing, Elizabeth convinces her husband that they must build a separate bathroom for Aibileen, which is an unfinished little box of a room.

Ultimately, combined with other incidents, Aibileen agrees to provide an anonymous interview. She's worried, not just that she might lose her job over it, but that she could face mortal danger; black people have been killed for less. What she and Skeeter are doing, in the privacy of Aibileen's home, is not strictly legal, either.

In her own home, Skeeter wonders what happened to longtime family maid Constantine (Cicely Tyson). Skeeter's mother Charlotte (Allison Janney) tells her, tight-lipped, that Constantine left to be with her family in Chicago, but Skeeter keeps asking, even as her cancer-stricken mother pushes her toward marriage.

Aibileen's outspoken friend Minny (Octavia Spencer), meanwhile, is fired by Hilly Hillbrook after Minny appears to have used her home's "only for whites" bathroom. Hilly's mother, Missus Walters (Sissy Spacek), loves Minny but agrees that Minny has gone too far. Adding insult to injury, Hilly lyingly brands Minny a thief, forcing her to seek employment with town outcast Celia Foote (Jessica Chastain, nearly unrecognizable from The Tree of Life). Celia is outlandishly dim but extremely sweet, without a prejudiced bone in her body, and she warmly welcomes Minny, known as the best cook in town, to her little plantation-style estate. Celia needs help with all things domestic, but she also badly needs the friendship of a sympathetic woman.

What is genuinely moving about the film is its portrayal of blatant, institutional discrimination and very personal racial segregation in the not-so-distant past. From that angle, the emphasis on everyday bathroom issues is powerful: How humiliating and outrageous to not even be allowed to answer the call of nature!

My misgivings arise, however, from the film's clear perspective that, if not for Skeeter, Aibileen would never have been able to voice her true feelings, that she would have remained a humble and humbled woman, forever cowed by the fear of the white man. For all her outspoken nature, Minny fares only a little better; she lives in fear of her abusive husband, who we never see.

The white people in the movie are divided up neatly into camps: the good (Skeeter, Celia, Missus Walters, Charlotte), the bad (Elizabeth), and the ugly (Hilly). Even most of the "good" white people, though, are complicit to some degree with the racism of those around them. Skeeter, seemingly ignorant until she's returned home after four years away, observes but keeps her thoughts private. Missus Walters doesn't think she's racist, much like her daughter Hilly. Charlotte is a loving mother but is beholden to the way that she was raised.

Octavia Spencer is the heart and soul of the piece, earning most of the laughs, while Viola Davis is the conscience, oozing sincerity and heartache. Adapted for the screen and directed by Tate Taylor, a friend of the book's author, The Help is well-meaning and well-acted. It should go down well with everyone who loved The Blind Side.

Help yourself.

The Help opens today in wide release in the U.S. Check local listings for theaters and showtimes.

Credits: Photos by Dale Robinette, © DreamWorks II Distribution Co., LLC. All Rights Reserved.