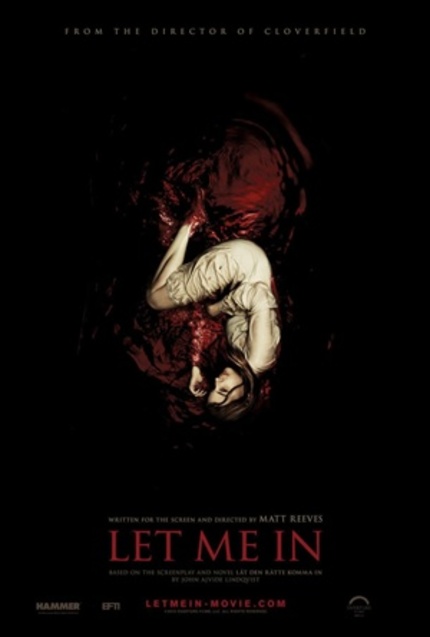

TIFF 2010: LET ME IN Review

In many ways I am jealous of those who will be able to experience Matt Reeves' Let Me In cold, with no exposure to either the source novel by John Ajvide Lindqvist or the previous Swedish film adaptation by Tomas Alfredson. I say this not because the Reeves film does not hold up to the quality of the Alfredson picture, which it does. I say this not because it does not honor the source material, which it also does. No, I say this because those people who are coming to the picture cold will be the fortunate ones who are able to slip into it and experience a good story well told without fighting the urge to maintain a running log of what changed where and why between the three different versions of the tale - all of which are quite similar and quite distinct from one another on a number of points.

Let Me In is the story of two adolescent children, one of whom is not. It is the story of Owen, a twelve year old boy living in a cheap apartment trying to cope with the twin pressures of horrific bullying at school and the slow collapse of his parents' marriage. And it is the story of Abby, the girl who moves into the apartment next door late one night, walking barefoot through the snow. Never seen during the day and initially hostile during chance encounters, it is not long before Owen feels that Abby is his one true friend and confidante. But what to make of the troubling series of gruesome murders that coincide with her arrival?

A most unusual coming of age story, Let Me In is the story of a blossoming relationship between a boy and a vampire and it is one that has now proven to be quite resilient, taking on slightly different shapes and forms as it shifts between mediums and languages. And though the Reeves take is not exhaustive by any means - the book is considerably richer and more complex than either film version - it is nonetheless remarkable on a number of levels.

First, and most strikingly, it boasts striking performances from the entire cast. While supporting players Elias Koteas and Richard Jenkins both bring surprising depth to their relatively brief screen time the weight of the film rests on the shoulders of young stars Chloe Moretz and Kodi Smit-McPhee and both are absolutely stellar. At least one of the two young performers are on screen for better than eighty percent of the running time, meaning strong performances were necessary if the film was to hang together and both deliver in a big way with subtle, restrained performances.

Second, it is remarkable for its skillful manipulation of mood and tone. Owen's life is a quiet tragedy, that of a sensitive boy collapsing in on himself emotionally and retreating into fantasies of violence against those who have hurt him when he meets Abby, someone who is - ironically - more than capable of the type of violence Owen dreams of but who seems to dream of the life she lost long ago. Why they're drawn to each other seems obvious, why they should stay far apart seems even moreso. The roots of their tragic relationship inform the entire film with a sort of muted-palette sadness, but Reeves and company find shades of meaning within that base level emotion while also punctuating it with sequences of building tension and shocking bursts of violence.

And, finally, it is remarkable for the way it manages to be both faithful and true to the earlier versions of the story while also giving the film a distinct feel of its own. It is a pleasant surprise how easily Reeves is able to make this feel like an inherently American story - one that plays on the inner rot of the Regan years, the hysteria of the Satanic Panic years and the rise of the Religious Right - rather than a thinly veneered copy of a foreign original. Though specific moments and shots will feel familiar to fans of the earlier film, the overall picture feels very much like Reeves' own. How does he accomplish this?

First, Reeves introduces a structural change right at the outset. He starts the story at an entirely different point, thereby shifting the focus from the Oscar / Owen character who drove the Alfredson film and on the Eli / Abby, who drives the Reeves picture. Do the actual events change? No, but the manner in which they are presented very certainly does and that makes a very subtle but important difference in the feel of the picture.

Second, Reeves narrows the focus of the story down, making it as purely about Owen and Abby as he possibly can with secondary characters appearing only to the degree they are needed to drive the story of the core duo. This narrowing process has become more pronounced from version to version with the book boasting a far broader involvement with a much larger world than is present in the Swedish film, which limits the action to the children, their parents / caregivers and a small collection of fellow residents, down on to the Reeves film which is so tightly focused on the children that Owen's father does not appear on screen at all, nor do the group of gossiping friends from the earlier versions. This move is somewhat double edged. On the positive side, it's very hard to argue with any move that gives more screen time to Moretz and Smit-McPhee and the relationship between them. Once again, they are remarkable. On the other side, however, the broader space provided a bit more context for the events of the story and knowing Abby's victims better made their deaths more shocking.

Much has been written by angry fans of the Alfredson film against this one based on early trailers and script reviews from dubious sources. To those who have been following those conversations, no - it is not a shot for shot remake. Yes, many sequences are quite similar but many others are not. The structure of the film is quite different, the internal focus shifted slightly. As for script reviews claiming massive revisions to the source material, disregard those entirely. They simply are not true. The back stories of the children have not been changed in the slightest, with the obvious exception being that they now live in America. Some issues are simply not touched on - which I will not go in to for spoiler reasons - but there is nothing about either character that contradicts existing canon. This is a true, respectful treatment of the original material.

As for the question of Swedish or American, which version is better? I simply don't know if I can offer an answer to that because the experience of watching the two versions is so wildly different. The Alfredson film was my first exposure to this story, so everything was fresh. Since then I have read the novel, which dives much more deeply into any number of issues barely hinted at in the Alfredson film. And approaching this film it was simply impossible to just sit and watch and experience the story fresh because comparisons to both book and earlier film were spinning in my head throughout the entire run time. And this, I think, is about the only argument that I'll accept when it comes to opposing film remakes this close to the previous film version - that things are still so fresh that it is almost impossible to judge the new version on its own terms. What I do know is that while neither film is perfect both are pretty damn good and a host of people unfamiliar with the story are about to get a treat.

Let Me In is the story of two adolescent children, one of whom is not. It is the story of Owen, a twelve year old boy living in a cheap apartment trying to cope with the twin pressures of horrific bullying at school and the slow collapse of his parents' marriage. And it is the story of Abby, the girl who moves into the apartment next door late one night, walking barefoot through the snow. Never seen during the day and initially hostile during chance encounters, it is not long before Owen feels that Abby is his one true friend and confidante. But what to make of the troubling series of gruesome murders that coincide with her arrival?

A most unusual coming of age story, Let Me In is the story of a blossoming relationship between a boy and a vampire and it is one that has now proven to be quite resilient, taking on slightly different shapes and forms as it shifts between mediums and languages. And though the Reeves take is not exhaustive by any means - the book is considerably richer and more complex than either film version - it is nonetheless remarkable on a number of levels.

First, and most strikingly, it boasts striking performances from the entire cast. While supporting players Elias Koteas and Richard Jenkins both bring surprising depth to their relatively brief screen time the weight of the film rests on the shoulders of young stars Chloe Moretz and Kodi Smit-McPhee and both are absolutely stellar. At least one of the two young performers are on screen for better than eighty percent of the running time, meaning strong performances were necessary if the film was to hang together and both deliver in a big way with subtle, restrained performances.

Second, it is remarkable for its skillful manipulation of mood and tone. Owen's life is a quiet tragedy, that of a sensitive boy collapsing in on himself emotionally and retreating into fantasies of violence against those who have hurt him when he meets Abby, someone who is - ironically - more than capable of the type of violence Owen dreams of but who seems to dream of the life she lost long ago. Why they're drawn to each other seems obvious, why they should stay far apart seems even moreso. The roots of their tragic relationship inform the entire film with a sort of muted-palette sadness, but Reeves and company find shades of meaning within that base level emotion while also punctuating it with sequences of building tension and shocking bursts of violence.

And, finally, it is remarkable for the way it manages to be both faithful and true to the earlier versions of the story while also giving the film a distinct feel of its own. It is a pleasant surprise how easily Reeves is able to make this feel like an inherently American story - one that plays on the inner rot of the Regan years, the hysteria of the Satanic Panic years and the rise of the Religious Right - rather than a thinly veneered copy of a foreign original. Though specific moments and shots will feel familiar to fans of the earlier film, the overall picture feels very much like Reeves' own. How does he accomplish this?

First, Reeves introduces a structural change right at the outset. He starts the story at an entirely different point, thereby shifting the focus from the Oscar / Owen character who drove the Alfredson film and on the Eli / Abby, who drives the Reeves picture. Do the actual events change? No, but the manner in which they are presented very certainly does and that makes a very subtle but important difference in the feel of the picture.

Second, Reeves narrows the focus of the story down, making it as purely about Owen and Abby as he possibly can with secondary characters appearing only to the degree they are needed to drive the story of the core duo. This narrowing process has become more pronounced from version to version with the book boasting a far broader involvement with a much larger world than is present in the Swedish film, which limits the action to the children, their parents / caregivers and a small collection of fellow residents, down on to the Reeves film which is so tightly focused on the children that Owen's father does not appear on screen at all, nor do the group of gossiping friends from the earlier versions. This move is somewhat double edged. On the positive side, it's very hard to argue with any move that gives more screen time to Moretz and Smit-McPhee and the relationship between them. Once again, they are remarkable. On the other side, however, the broader space provided a bit more context for the events of the story and knowing Abby's victims better made their deaths more shocking.

Much has been written by angry fans of the Alfredson film against this one based on early trailers and script reviews from dubious sources. To those who have been following those conversations, no - it is not a shot for shot remake. Yes, many sequences are quite similar but many others are not. The structure of the film is quite different, the internal focus shifted slightly. As for script reviews claiming massive revisions to the source material, disregard those entirely. They simply are not true. The back stories of the children have not been changed in the slightest, with the obvious exception being that they now live in America. Some issues are simply not touched on - which I will not go in to for spoiler reasons - but there is nothing about either character that contradicts existing canon. This is a true, respectful treatment of the original material.

As for the question of Swedish or American, which version is better? I simply don't know if I can offer an answer to that because the experience of watching the two versions is so wildly different. The Alfredson film was my first exposure to this story, so everything was fresh. Since then I have read the novel, which dives much more deeply into any number of issues barely hinted at in the Alfredson film. And approaching this film it was simply impossible to just sit and watch and experience the story fresh because comparisons to both book and earlier film were spinning in my head throughout the entire run time. And this, I think, is about the only argument that I'll accept when it comes to opposing film remakes this close to the previous film version - that things are still so fresh that it is almost impossible to judge the new version on its own terms. What I do know is that while neither film is perfect both are pretty damn good and a host of people unfamiliar with the story are about to get a treat.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.