Fantasia 2010: Philip Ridley Talks HEARTLESS

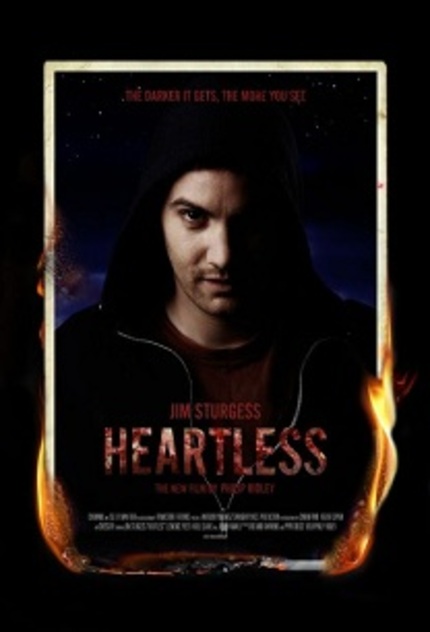

Fantasia is extremely proud to be hosting the North American premiere of Philip Ridley's Heartless, his first return to the big screen since The Passion of Darkly Noon in 1996. Genre fans know Ridley primarily for The Reflecting Skin - an unsettling and unconventional horror film that was universally praised as one of the best films of the 1990s - and with Heartless, he returns to the folklore-infused psychological terrain of The Reflecting Skin, and the murky physical terrain of The Krays, which he wrote in 1990. He was kind enough to offer his thoughts on some of the recurring themes in his work.

You've been hailed as a cinematic visionary by countless film critics and yet film is a medium you turn to infrequently. Why is that?

Well, the kind of films I've been interested in making are not very easy to get off the ground. They don't fit into a neat box or category. So, for example, I've never shown an investor a script and had them say, 'Hey! I get this totally! How much money do you want?' It's always more like, 'Mmm, this could be...interesting. Tell me a bit more about it.' And that 'tell me a bit more' process can go on for a very, very long time.

The film business, generally, prefers films to be a clear-cut, simple genre. That's how they feel confident of getting a big opening weekend box office. Don't get me wrong - I love some of those films too. But, as I say, the films I've made so far have not been like that. Heartless, for instance, deliberately plays around with genre conventions and audience expectations. It's a mash-up of lots of different things. This is the way the narrative works. The narrative itself if a labyrinth that Jamie, the lead character, is lost in. The film never lays its cards on the table and says, 'Okay! I'm this kind of film.'

Sometimes the genre aspects and tonal qualities deliberately clash with each other. One critic described Heartless as 'a mash 'n' clash movie'. I don't know if they meant it as a compliment but, actually, I quite like the description. For me, this 'mash 'n' clash' is an exciting journey to be on. You open a door, or you turn a corner, and the whole film goes in another direction. I've always loved the way Hitchcock did that in Psycho. You know how one moment you think it's a thriller about Janet Leigh robbing a bank, then she meets a policeman and you think it's gonna be about the cop chasing her, but then the policeman disappears and is never seen again, then - just when you think you have a grip on the film - the shower curtain opens and it becomes a horror film. I really admire the narrative daring of that.

In The Reflecting Skin, the little boy hears a vampire story and then becomes convinced that the woman up the road is a vampire. Do you think horror or dark content is important for children to experience in a fantasy context? What purpose does it serve for them?

It's the ghost train ride! Children love it. We all have a need to experience the ritual of the dark...but in a safe environment. That's the key. After all, the reason the ghost train is so popular is because there are no real ghosts in it. Most of the classic stories for children have an element of darkness at their heart: death (as in The Secret Garden or Peter Pan), fighting evil (the Narnia books) or just plain madness (Alice in Wonderland). The Brothers Grimm stories, for example, are full of the most incredible violence. I was reading one the other day where a child's head gets cut off! It's stories like this, by the way, that are referenced throughout Heartless. Jamie has to do something by midnight (Cinderella), he has to cut someone's heart out (the proposed fate of Snow White), he rescues someone from a beast (Beauty and the Beast).

We all need the vicarious journey of tales like this, but especially children. They instinctively crave it. It's like they know, in their hearts, the world will be a complex and potentially dangerous place, and they need as much preparation for it as possible. But, as I say, it must always be in a safe context and it we must never impose any of our adult cynicism on a child. Yes, Snow White may bite a poison apple and be put in a crystal coffin...but a kiss must always bring her back to life.

Where does your interest in children's writing come from? Are there things you feel you can do in children's lit that you can't do when writing for adults?

To be honest, the first book of mine that was published as a kid's book, Mercedes Ice, was not written as such. I just wrote this story and I gave it to my agent and it was she who said, "You know, I think you've written a children's novel.' And that's how it all started. But, in a way, it was something I'd always been interested in. It's the purest form of storytelling. And the art of storytelling has always fascinated me. My shelves are full of books on myths and legends and fairytales from around the world.

I was a voracious reader as a child. I still read lots of children's novels. Writing for children is a great discipline: you can't cheat when you tell a story to children. The characters have to be clear and their motivations have to ring true at all times. You can't have three pages of carefully worded prose to get you out of a narrative loophole. You have to nail it - Bang! First time! A child can detect something that doesn't quite work a mile off. You try telling a story to a classroom full of children - as I have, many times - it's the most difficult audience in the world. But is also teaches you so much: how to be clear, how to keep a story moving, how to create characters people engage with. And you better learn this quick if you're a children's novelist because, believe me, you do not want to be sitting in front a classroom full of bored children!

The other thing is...you can sometimes be a lot more inventive in children's stories than you can when writing for adults. This is a huge generalisation, of course, but...well, it seems to me so long as you are true and honest, so long as you create characters that children engage with and believes in, children are willing to follow your narrative almost anywhere. They don't get all cerebral and self-judgmental about what they are enjoying. They don't worry if it's 'cool' or 'high art' or 'low art'. If they're enjoying the ride....that's all that matters. I love that freedom.

In Heartless there is also an unhappy young man who meets demons - a young man with a large birthmark who thinks he's ugly. Is there meant to be some ambiguity as to whether the monsters are his projections?

There's a wonderful quote from the artist Louise Bourgeois that I kept saying while we were shooting the film: "My emotions are my demons." Jamie, the lead character played by Jim Sturgess, is a like a lot of the young people I've met: he cannot make sense of the world around him. The violence, the hypocrisy, the injustice - all this haunts Jamie as palpably as any ghost. In other words, Jamie is a character haunting by the world in which he lives. I think this is a very contemporary sort of character. It's certainly touched a nerve judging from things that have been said to me after screenings and by the emails I've received.

Can you talk about the contrasting geographical landscapes in The Reflecting Skin, The Passion of Darkly Noon and now Heartless, and how the environment plays into the story? Is there a bit of a return to the world of The Krays with Heartless?

Well, I love shooting on location. It's odd, you know, 'cos as a person I'm pretty much a recluse. I'm at my happiest when I'm all alone in my little flat in East London. I can go for days, sometimes weeks, without seeing anyone. I hate parties and all the razzmatazz of releasing a film. My producers have to drag meet kicking and screening to screenings. And yet, when it comes to film, I love the big outdoors and big landscapes. For me, that's part of the cinematic language of film. I grew up loving the films of David Lean. I remember going to see the restored version of his Lawrence of Arabia when I was an art student and just being blown away by it. The sheer scale. Those deserts and sunsets. And I also like the idea of using the landscape as an emotional thing. In other words, the landscape becomes a character in the film. The vast yellow wheat and sky of The Reflecting Skin, the twisted, magical forest of The Passion of Darkly Noon, and the graffiti covered labyrinth of streets in Heartless.

And, yes, in a way Heartless is a return to the world of the The Krays. Although, I think, it feels very different in Heartless. It's much more a psychological state than it was in The Krays. I've always wanted to shoot something in East London. I had a long list of corners and streets that I wanted to shoot scenes in. For me, it's a very beautiful location. It's magical and menacing in equal measure. Most of the locations in Heartless are very close to where I live. I walked to set most mornings. In fact, the scene on the roof where Jamie meets Papa B for the second time - that's the roof of the block of flats where I live. Indeed, it was where I was born. Yes, I'm still living in the same place where I grew up. How sad is that, eh?

Comic artist Robert Crumb once told me he quit playing music because he found that "you can't serve two masters". But you seem to have a myriad of talents that you actively pursue - directing, writing films, writing poetry, songwriting, painting, photography, directing plays - is there one thing you prefer doing over the others? Do you have a strategy for balancing all these things?

You know, I've been asked this so much and I always find it so hard to answer because, for me, I'm only doing one thing: I'm telling stories. Sometimes I think of a story and it comes out as a film, sometimes a stage play, sometimes a photograph...and so on. The way I like to think of it is this: Say you're in a plane and you look down and you see mountain peaks sticking up through the clouds and you think, 'Oh, look at all those different mountains.' But then the clouds clear and you realise it wasn't different mountains at all. It was just different peaks of the same mountain. Well, that's what all my work is like, I guess. It's different peaks of the same mountain.

- Kier-La Janisse