Full Disclosure: ScreenAnarchy's Lists of Shame - April (Part 1)

We carry on apace with this epic undertaking - finally each tackling a classic from our individual Lists of Shame, and sharing our thoughts with you the readers. This month sees the work of such cinematic luminaries as Ozu, Bergman and Cimino go under the spotlight, scrutinised by our writers for the very first time. So without further ado, let's go:

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (dir. George Roy Hill, 1969 USA)

Winner of 4 Academy Awards, including Best Original Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Original Score and Best Original Song, winner of 8 BAFTA Awards, including Best Film

Todd Brown, Founder & Editor:

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is, to put it mildly, a very odd movie. A very odd movie with a litany of elements that should keep it from working at all. Plot and character development - what are those? It glosses over major plot points with montages made up of still photographs, the main characters are deeply flawed at best (Butch) and quite unlikeable at worst (Sundance), if you actually stop to think critically about their behaviour and how they treat the people around them. There is literally nothing at all driving the narrative and it features Cloris Leachman as a sex object. And for the love of God, what the HELL is up with that Burt Bacharach musical interlude!?! Really!? Bacharach in a Western? Whose idea was that, anyway?

And yet...

And yet it does work. It's a hugely entertaining film that in retrospect seems to fall into this transitionary space between the classic John Wayne Westerns that preceded it and the gritty 70s indie antiheroes that were just around the corner. But mostly it works because of one very great asset: It has in-their-prime Paul Newman and Robert Redford bickering at each other for nearly two hours. And, yes, that's enough to make one hell of an entertaining movie.

Smiles of a Summer Night (dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1955 Sweden)

Winner of the Best Poetic Humour Award at the Cannes Film Festival, nominated for 3 BAFTAs, including Best Film From Any Source

Peter Martin, Managing Editor:

By the time I began exploring films from outside the U.S. in the late 1970s, Ingmar Bergman had already been fossilized as a master of Cinema. As with other masters, double-bills of his films toured the repertory theater circuit, and I sampled his work, but it never provoked the kind of reaction I had enjoyed with other established filmmakers. I was left with an impression of Bergman as stoic and heavy-handed that remained unchanged when I sampled his work again in the VHS and DVD eras.

Having enjoyed the generally playful Summer With Monika (1953), I hoped that Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), the first of Bergman's films to be released in the U.S. (in 1957), might break my mental logjam. Even though it's been described as a comedy, and it does have its light-hearted moments, Smiles of a Summer Night is a picture of substance that seeks to examine the greater issues of faith, love, fidelity, and betrayal. Bergman fills the picture with characters who are forever justifying their actions, which are inevitably self-motivated, and which struck me as almost entirely repellent.

Despite moments, scenes, and sequences that are worthy of admiration for their conception and execution, Smiles of a Summer Night left me as cold as a Swedish winter night.

Tokyo Story (dir. Ozu Yasujiro, 1953 Japan)

Ryland Aldrich, Festivals Editor:

Having gone through a pretty extensive Japanese Classics phase, I had to double check the Tokyo Story wiki to make sure I indeed had never seen Ozu's masterpiece. But somehow the classic had slipped through the cracks - sad as it is to admit. But that's exactly the point of this series and every classic never seen is a potentially wonderful film watching experience yet to be had. This is very much the case with Tokyo Story; a film absolutely every student of storytelling in any form must make an effort to see.

The brilliance of Ozu's film lies in the exploration of the mundane. Ostensibly this is a story about post-war Japan and the damage that modernization causes to the traditional family unit. But in reality, it's a timeless story of generational divides, just as relevant today as it was in Japan 60 years ago (or, say, 19th century Russia). It's a brilliant examination of life's disappointments - and why we never seem to make the time for our parents that they deserve, all told with Ozu's filmmaking grace so rarely achieved by other directors. This is a gem that everyone who has missed it should go watch now. And when you are done, go call your mother.

Niels Matthijs, Contributing Writer:

From all the films that I listed for this little endeavour, I had the highest hopes for Ozu's Tokyo Story. I've only just started to discover Ozu's films and even though I wasn't exactly overwhelmed by my first impression (Good Morning and A Story of Floating Weeds), there was something majestic about Tokyo Story. A film named by many as one of the best films ever made, touted as a celebration of minimalism and mundane beauty. In my mind, Tokyo Story was supposed to be a prehistoric predecessor of Tokyo.sora.

But the reality is quite different. It seems that Japan changed a lot in those 50 years. I'm an absolute drooling fanboy of stilted and communication-deprived Japanese dramas, but surprisingly enough Tokyo Story didn't really fit that description. Dialogue is an important aspect of the film and while not very direct in expressing their emotions, characters clearly overact the masks they put on. Expect plenty of fake smiles and meaningless chit-chat throughout the film.

I didn't quite like the split story structure either. The first part of the film is dedicated to an old couple traveling to Tokyo to visit their children, the second part is reserved for a sudden death and a reverse travel. A new story arc starts halfway through, which is quite a blow if the first part failed to engage.

What bugs me the most though is that I fail to see the actors as "real people". Ozu makes films about the mundane and for that to work the characters need to come off as real. To me both their social apathy and their hidden emotions are overstated, turning them into caricatures that destroy the minimalist power of the film.

I like Ozu's clean and strict visual style, which does lend the film a peaceful and stylish atmosphere. Ozu scores extra points for the last scene, which, even though a little too direct, paints a powerful and emotional picture of the main character of the film. Sadly these are just slim highlights in an otherwise overly long and disappointingly caricatured film that left me wanting. Tokyo Story is definitely not the film I hoped it would be.

Cinema Paradiso (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1988 Italy)

Winner of the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, winner of the Grand Prix du Jury at the Cannes Film Festival, winner of 5 BAFTAs, including Best Film not in the English Language

James Marsh, Asian Editor:

Cinema Paradiso is one of those foreign language films that you just feel like you've already seen, even if you haven't. It arrived at a time when Miramax was making a name for itself, both nurturing homegrown talent like Steven Soderbergh, Kevin Smith and Quentin Tarantino, while also scooping up safe, awards-friendly fare from Europe that would play well to the adventurous middle classes. Sadly, Harvey Scissorhands, as one half of the Weinstein brothers was known, felt that Western audiences didn't need to see all 155 minutes of Giuseppe Tornatore's nostalgic love letter to Cinema, nor did they need the film's original title. And so, Nuovo Cinema Paradiso became the 124-minute Cinema Paradiso, and went on to earn itself a Best Foreign Film Oscar for its troubles.

The film itself is as charming - and as slight - as I had both hoped and feared. On hearing the news that "Alfredo" has died, successful filmmaker Salvatore Di Vita (Jacques Perrin) becomes swept up in the memories of his childhood, and how he fell in love with Cinema. In a picturesque Sicilian village that immediately evokes Federico Fellini's Amarcord, the adorable, yet mischievous young Salvatore makes a nuisance of himself around the local picturehouse, equally fascinated by the films themselves and the projection booth that shares them. Alfredo (Philippe Noiret) is the projectionist, who begrudgingly takes the young lad on as his assistant, thus beginning a friendship that will span decades.

It is no surprise that the film became so successful, as it not only features simple, honest folk in gorgeous mediterranean locations, but is also infatuated with Cinema itself. That said, the film also breezes through a particularly turbulent period of Italian history with only the briefest of acknowledgments to what was going on across the water. There is no denying the film's beauty and earnestness, nor that it is incredibly charming, but Cinema Paradiso never surprises, and delivers exactly what I expected of it. To be honest this is precisely why I hadn't rushed to see the film before now. While this kind of sweet confection engaged and entertained me, if I know exactly what I'll be getting, I'll often go looking for my cinematic gratification elsewhere instead.

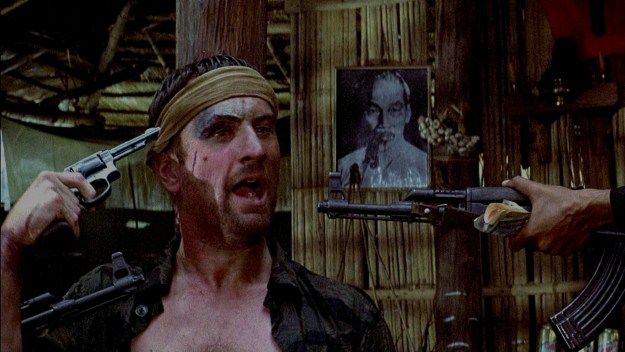

The Deer Hunter (dir. Michael Cimino, 1978 USA)

Winner of 5 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, winner of 2 BAFTAs, including Best Editing and Best Cinematography

Andrew Mack, Contributing Writer:

After Oliver Stone's Platoon, I went on a Vietnam War bender. I took out books at the library (ah, the Internet-less year was 1986). I watched other Vietnam movies that came out before and after. I bought the comic book The 'Nam. I bought almost all of the Vietnam: Ground Zero novels by Eric Helm (Kevin Randall and Robert Cornett). I was thirteen years old, four years removed from the Falklands War in which my homeland Britain was involved in, and needed a war damn it!

Yet somehow, despite all my efforts to know as much about the Vietnam War, I somehow missed The Deer Hunter. If I recall correctly I heard from someone who had seen it and they told me there was hardly any war action in it. So I gave it a miss, because clearly at the age of thirteen I was a sensationalist and wanted only action, not the repercussions. Now much older, perhaps wiser, I have come back to this film, maybe to close a chapter or bring some sense of fulfilment.

I like The Deer Hunter. It shows that hometown side of the war that I was missing from those other films. And it is less dramatic than Stone's second film in his trilogy, Born on the Fourth of July, which attempted to do the same in an overt sense. The cast is tremendous. Meryl Streep just looks luminescent and pure. The emptiness in Walken's eyes at the end of the film during the roulette scenes is haunting. It was a shame that I had already seen John Savage lose his marbles in The Thin Red Line because I did an "Oh! That's the guy!" as soon as the POW scenes started.

As it stands now I admire what this film set out to do just three years after the Americans had fled. The way the POW scene plays out is damned harrowing. I had yet to see a portrayal of the chaos in the streets of Saigon when De Niro returns to find Walken. The quietness, with which the film shows how family and friends were forever changed when the soldiers returned from overseas, was subdued yet moving. Had I seen this when I had just become a teenager, the purpose of this film would have been lost on me, because it would not have had enough war action in it. That would have been a shame.

Dave Canfield, Contributing Writer:

The Deer Hunter is a deeply disturbing film, precisely because it's so smart and it's more relevant than ever. Michael Cimino gives us three men who could be from any small town in America. What do three small town steel workers do when they go off to war? They start out full of bravado, ready to serve the myth in their heads that bears their country's name. They celebrate leading up to departure. They get married, or propose marriage as if it were some sacred talisman that death or disfigurement would not dare defile. They get drunk, go on a final hunting trip. But, when they hit the ground running, they find that the war has ways to break them that their ideals never dreamed of.

Because that's all war does.

Cimino let's his soldiers come home. He let's them continue to have some national pride. He even hints that they will return to some form of normalcy. But he shows the price that all concerned pay for that paltry return on the usually unnecessary investment of human conflict.

War isn't about ideals.

Cimino shows the war for what it was, a greedy lust-inciting bitch. To be sure those lusts are varied; self pity, self-despair, self-destruction among them. But they also all end at the same road. War is a heart rippin', tenderizin', grindin' machine whose on/off switch looks an awful lot like the trigger in a hugely monied game of Russian Roulette.

War only needs one shot.

A lot of people were angry with Cimino about the way his film uses the Vietnamese. No doubt they get pretty rough treatment at the story's hands. But Cimino certainly isn't suggesting all is well in the land of mom and apple pie, and steel mills. In fact I would say he's more than a little heart broken. He's using the Viet Cong here (and the roulette) as a metaphor for the pitiless situation GIs faced, and were so often irretrievably broken by. His film is asking questions that can only be asked through gritted teeth.

Why the hell do we sell war to small town America like it's a badge to pin on, or a story you share with strangers to get free drinks at the bar?

Cimino knows that all these guys ever had, and were lucky to have, was the love of some people back home in that small town, the same people who will take them back now however they come, ripped up inside, missing limbs on the outside, or even in a box. Their loved ones won't ask them to answer that damn question. That's what we elect leaders for, right?

The same leaders, who war after war, seem to be the guys running the Russian Roulette of war, taking the bets, and shipping the bodies out of the way.

The Shining (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1980 USA)

Ben Umstead, East Coast Editor:

I may have never read Stephen King's The Shining, and just prior to this writing I had of course not seen Stanley Kubrick's. But I do very much know The Shining. Err, excuse me, The Shinning. Yes, thanks to The Simpsons' spoof, I've been familiar with all the basic plot points for years.

For the record I'm not a fan of King as a writer. While I think he's a great ideas man, I've never been taken by his prose. And as for Kubrick, well... as someone with a filmmaking background I respect the hell out of him, but as an audience member I am rarely compelled by his films. So, how did I find The Shining?

Oh, it's most certainly a bombastic experience. It's one of those films that is essentially an opera minus the singing. It is loud and big and not in the least bit frightening and sometimes very funny. To be clear, I am rarely ever scared while watching a horror film. The exceptions remain Romero's Night of the Living Dead and Kurosawa Kiyoshi's Pulse. I think that's because both those films have a much larger social conscious in their construction, which is really the seed for any visceral or psychological scares therein. As it is, I am not so sure Kubrick was even intending The Shining to be straight-up horror, but rather a deconstruction of the genre, or even perhaps a parody of it. What is clear is that, like many of Kubrick's films, The Shining is about the destructive dominance of the male ego.

It is also the most obvious example of his one-point perspective approach to Cinema. Symmetry is key for Kubrick. Very much like a ride, he places each and every member of the audience (no matter where they are actually sitting) in this perfect seat, dead set at one end of the camera; we're peering down from one side of the lens to the other, down the rabbit hole, through a portal and into another dimension. Kubrick's is a Cinema of space and place. From the war room in Dr. Strangelove, to the spaceship in 2001, the trenches in Paths of Glory and the Overlook Hotel here, Kubrick is absolutely compelled by places; how people move through them and change them, and more importantly how the places themselves change the people. The Shining constructs a place embodying absolute madness.

As fun as Jack Nicholson is here, and as captivating as Danny Lloyd is as his son, the star of the film is indeed the Overlook Hotel. Everything else is an extension of this haunted, out-of-sync, yet symmetrical place. Call it Hallway: The Movie. We know every nook and cranny, every corner, every turn, so that when the shit truly hits the fan we're not thrown out of orbit by mania or fear, but pulled in, deeper and deeper into this other dimension... into something so uncanny that it must only be ourselves looking back in awe.

The Seventh Seal (dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1957 Sweden)

Winner of the Special Jury Prix at the Cannes Film Festival

Ard Vijn, Contributing Writer:

If there is anything that ought to be highlighted by this whole "List of Shame" thingy it is that the largest gaps in my film knowledge all have to do with European film history. I still managed to mostly side-step the issue by inserting as many Japanese and American classics on my list as possible, but there is no denying I know too little about Truffaut, Godard, Kieslowski, Fellini and Bergman to feel comfortable on the subject.

Case in point: this month I saw my first Ingmar Bergman film ever, The Seventh Seal. Touted as a classic, quite possibly one of the most important films ever made, a philosophical and cinematic masterpiece even, I approached it with appropriate awe. Would I be able to "get it"? Would this oft-parodied and endlessly referenced film enchant me?

I assume a second "no" is akin to confessing the first "no" as well. There is a lot I liked about The Seventh Seal, primarily the dark sense of humour and that the story turned out to be much more intimate than I had expected. On top of that it looks damn pretty as well, at times gorgeous in its black and white glory even. But the reason for its revered status eludes me.

I will credit Ingmar Bergman with not being pretentious, despite the heady approach or heavy subject matter. Watching The Seventh Seal, you get the impression he made the film because he was honestly interested in the questions asked in it, and that attitude shines through. He does not come across as claiming to know a great truth, and is not divulging it to his avid followers. But again, it made me like the film rather than love it. How much pondering and allegory can you put in a film before it seriously starts to damage the narrative?

I did not suddenly catch the Ingmar Bergman bug and do not feel a sudden urge to rush out and see his other films. Doesn't mean that I won't do that anyway, in time, but right now I do not feel the urge.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.