Full Disclosure: ScreenAnarchy's Lists of Shame - March (Part 2)

The Wages of Fear (dir. Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1953 France)

Winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes Film Festival, Golen Bear at Berlin International Film Festival, BAFTA for Best Film from any Source, Blue Ribbon Award for Best Foreign Language Film

I'm going to be brutally honest here. It ain't gonna be pretty and will probably put any serious film writing I do to question, but here goes... I found Henri-Georges Clouzot's The Wages Of Fear utterly boring. Yep. I'm certain one Jason Gorber is spinning in his easy chair right about now, so I'll imagine him asking this: "But how, Ben? How? It's one of the greatest suspense movies of all time! The slow build up of tension, the absolute moment-to-moment danger these men face it's..." That very well may be, and I won't deny the scenario about four down on their luck Europeans hauling containers of explosives across rugged South America just to get the cash to jet home -- not to mention the exploitive control the American oil company has over the region -- is good, it is, but I found little to be compelled by. Sure, Yves Montand has charm and I quite liked Georges Auric's score (the little of it there was), but had I not been watching this for an assignment I would have turned it off, just like I did ten years ago when I first tried to watch it. There's nothing wrong with the film, it's a fine production and has clearly earned its spot in the Criterion Collection, it's just one of those flicks that does nothing for me. I may be a poor film writer to say this, but I haven't the faintest reason why either, and I'm quite fine leaving it at that.

It's an hour before any real action takes place in The Wages Of Fear. For what is essentially a men-on-a-mission movie, there's a hell of a lot of men before we get to the mission. And that's no bad thing.

Henri-Georges Clouzot's film is a slow burn suspense piece for sure, and allows itself ample time to set up the character dynamics. Four down on their luck Europeans attempt to take a highly volatile payload of nitro-glycerine across 300 miles of perilous South American roads to stem an oil field fire for the Southern Oil Company (SOC). $2000 each is the prize (a somewhat heftier sum in 1953) that will help them all get home to their native countries. The down time spent with these characters before they embark on their truck-based adventure is crucial. Clouzot is fundamentally concerned with studying how different people respond to extreme pressure, and how personality traits can be so governed by context. Of the four men who set out, it is the friendship between Corsican playboy Mario and aging Gangster Joe that proves most compelling and gives the film its emotional core. Friendly when killing time, competing facets of their personalities are revealed once on the road - one is a ruthlessly driven leader, the other a washed-up, self-confessed coward. A climactic accident whilst navigating their truck through a pool of crude oil is the culmination of Mario's terrifying but logical single-mindedness, where friendship is subsumed by the instinct to survive and conquer. It's a masterful and horrible scene.

I didn't expect The Wages of Fear to be quite so long (two and a half hours) or, in places, so gruelling. But how much more affecting the action is for being germinated so thoroughly. Sadly the only copy I could get hold of was a dreadful R2 Optimum DVD, which had appallingly bad sound, dubious subtitles and seems to have been taken from a completely original (i.e. knackered) print riddled with unintentional jump cuts. I believe there is a Criterion disc out there, so do seek that out. Friedkin's remake, Sorcerer (1977), is now firmly in my sights.

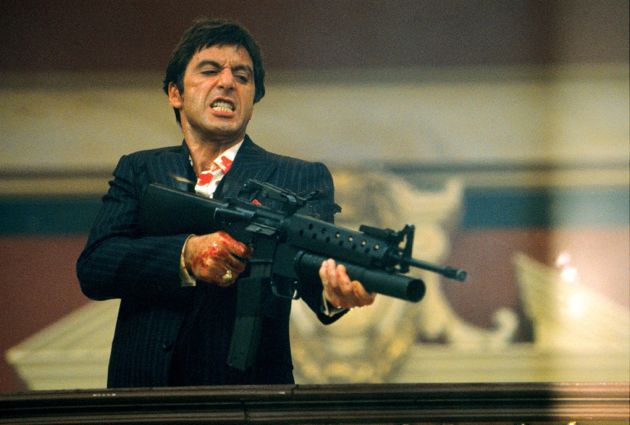

Scarface (dir. Brian De Palma, 1983 USA)

Nominated for 3 Academy Awards, including Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor and Best Original Score

Having avoided watching De Palma's Scarface for as long as I could, this series provided me with the opportunity to get this rabid monkey off my back. Of all the films on my list, this is one that raises the most eyebrows with, forgive me, the common man. It would appear that Scarface resonates the most, and is clearly the most iconic, to your Tuesday cheap-night cinema goer. You wouldn't have had to see Scarface to know its most iconic line about Tony's 'little friend'. The poster has adorned dormroom walls for decades, and every time I dropped the bomb that I hadn't seen it, it was as if I had committed some great travesty against humanity and cinema. How could I, a movie guy, have not seen Scarface!?! "It is awesome. It is the best movie. You can borrow my copy. Do you want my extra poster?"

Scarface is a decent enough gangster flick. I believe it has been done better before and since its release date but I can understand the appeal. Coming up from nothing and making a name for yourself. But that really isn't correct for Tony is it? He's a two-bit criminal stuffed onto a boat and sent somewhere else to carry out his trade. Out of sight. Out of mind. Like the British did when they sent criminals to Australia, only Miami is easier to get into. So I don't get how this can be inspirational to anyone but a thug (James Franco's Alien in Spring Breakers anyone?).

I believe we lost something around the mid-90s after the last great American gangster flicks gave way to the imitators and copycats. When those who emulated Scarface and made it their own mantra were old enough to try to make their own interpretation, perhaps? It has bred a culture of celebrating the gangster lifestyle, something that Western Cinema has tried to emulate since then and has failed over and over again. Because America has always celebrated the rebel, the anti-conformist, and the gangster. That was what the nation was founded on, right? Though they won't admit it when it comes back on them and their kids are smoking crack and shooting each other up over territory. Then it's bad, bad, bad. Yeah. Scarface is awesome that way.

Aside from my misgivings about celebrating gangster culture, the film is good. There are enough shocking moments and violent acts. The scene where Tony negotiates his first drug deal for Lopez is masterful at creating tension. The art direction, set direction and costume design really capture that gaudy era of the 80s. A rail thin Michelle Pfeiffer, barely a curve showing beneath her dresses, struts her stuff, while her lapels reach with all their might to the shoulders. Loud and bright printed shirts never go out of style. And the neon. Oh the neon. So far, of the films I have watched this year on my list, Scarface is the one I'll most likely watch again.

Apocalypse Now (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979 USA)

Winner of the Palme d'Or at Cannes Film Festival, winner of two Academy Awards, including Best Cinematography and Best Sound, nominated for 6 others, including Best Picture

Like many of the entries on our lists, Apocalypse Now was one of those movies - no, a cultural experience - that I'd taken in secondhand. I knew the disastrous history of its production, the myth of Apocalypse Now as a thing that happened to Francis Ford Coppola and his crew in the sweltering heat and hellish storms of Southeast Asia, and decades of movie watching has presented me with any number of homages, riffs, and outright thefts of Coppola's own trip down into Conrad's Heart of Darkness.

But none of that could have prepared me for how assaultive, how bruising actually watching the film in question could be. It thrashed me (via Martin Sheen's nerves-in-a-bucket Captain Willard) back and forth like a pit-bull from one surreal, hellish tableau to the next. I don't think I've actually used the phrase "terrible beauty" before, but there is something so terrible and beautiful about this film, a fantasy of war via acid flashback. It's an astonishingly sensual movie, every frame of the Philippines-as-Vietnam stand-in overwhelming in its color, hue, and intensity. The jungle is thick, and it's dangerous, and it's easy to get lost in, the water is black and it promises to drown you.

By following the traumatized, broken Willard we're only a half-step removed from the madness which claws at his sun-drenched, shell-shocked brain. When he finally meets Brando's shadowy, whispering Kurtz, it's not a confrontation between hero and villain but between Willard and the outer edges of his own mind, the blood-soaked, sensitive warrior.

Of the entries I've watched so far for this project, Apocalypse Now is the first to feel timeless, to feel rooted in something primal that's hard to shake off afterwards. It's kind of about The War but it's really about war, if you dig. I get why it's important (and why so many lazy storytellers fail to capture what's so gripping about it in their thin appropriations).

I should note, I watched the standard cut of the film and not the Redux released in 2000. Of course, I'll be diving right back in to see that (as well as the doc Hearts of Darkness for the complete immersion) but for the moment, Apocalypse Now is burned upon my mind - the sizzling heat, the blood, the despair, the confusion... the horror.

The Last Temptation of Christ (dir. Martin Scorsese, 1988 USA)

Nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director, two Golden Globes, including Best Actress and Best Original Score and the Mexican MTV Movie Award for Most Divine Miracle in a Movie

Is God real? Does he have a desire for my life, care about the choices I make? For many, such questions seem naive and I imagine The Last Temptation of Christ must come across as a character study in mental illness depicting, as it does, a man who allows himself to be tortured by his struggle over such beliefs. Of course this isn't a very close reading of Scorsese's film. The Jesus depicted in it, while not a historical Jesus exactly, is certainly directed by more than just the whims of madness. By film's end he has embraced what he is sure is a holy calling, one worth the trouble. Therein lies the rub. How to depict such stubborn resolve within the context of a sinless life?

C.S.Lewis, in his famous argument for the deity of Christ, says in Mere Christianity that we are left with no choice but to declare Christ a liar, a lunatic or Lord. It's compelling. Yet on close reading, which space does not permit here such an argument seems close to declaring Jesus as a champion in the basest of terms. Can such a Jesus, full of vigorous intent and self knowledge, truly be fully man and fully God? Didn't even those closest to him mistake him for all three at various times?

In writing his novel, Nikos Kazantzakis took care to stay well within the boundaries of fiction, pulling bits and pieces from the Gospels without relying on them entirely for dramatic effect. His desire was to explore a possible psychology of the human Christ, not to sully the idea of his deity. Scorcese takes Kazantzakis at his word, faithfully showcasing, via an incredible performance by Willem Dafoe, a Jesus that cries, wails, rages, doubts, and struggles to understand why a God of love allows pain. Worst of all, in the minds of the film's conservative critics, this Jesus comes dangerously close to abandoning his mission to save mankind for the sake of a woman's love and the comforts of family life.

My reaction? I don't think I've ever encountered a Jesus on film that seemed so utterly or so truly tempted. This is not a Jesus who is merely presented with the possibility of sin only to glibly turn away. This is a Jesus who wants, aches with need yet chooses to do that which he knows separates him from other men. How quickly brotherly love turns to callous indifference or even hatred when we refuse to share in our brother's sins or when he refuses to share in ours. This is a Jesus of lonely resolve, tortured by, sometimes confused by, but committed to his purpose.

What is perfect love in the face of temptation? To choose love even at the cost of one's own life in trust that such love matters. This is categorically not a Jesus who was in the words of the song , "Just a slob like one of us." This was an incarnation.

Bonnie and Clyde (dir. Arthur Penn, 1967 USA)

Winner of two Academy Awards, including Best Supporting Actress and Best Cinematography, nominated for eight others including Best Picture, winner of Best American DRama and Best American Screenplay awards from Writers Guild of America

Why didn't anybody tell me that Bonnie and Clyde was amazing?

My March entry into Full Disclosure is a film that I've owned on at least three formats, often in very fancy special editions, but have never sat down and watched. No particular reason, I just like collecting stuff, and this was one I felt I should own. Thankfully this project forced me to sit down with Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker for a couple of hours and boy was it fun!

There are gaping holes in my film experience when it comes to this time period, and filling them is something I enjoy immensely. As such, many of Arthur Penn's films have escaped me, but I figured this was as good a place to start as any. Warren Beatty I was little bit more familiar with, and his Clyde Barrow is a charismatic force of nature, only just contained by Faye Dunaway's rambunctious Bonnie Parker. Throw in a scenery-chewing turn from the great Gene Hackman and a wonderful cameo from Gene Wilder and you've got one goddamned entertaining film on your hands.

I'd heard so much about the balletic violence of the film's conclusion that I expected that to be the apex of the film's impact on me, however, that was far from true. The combination of Penn's direction and the screenplay by David Newman and Robert Benton makes for a fast-paced emotional rollercoaster that earns every bit of hype it's garnered over the last forty years.

When I was first asked for this crazy endeavor I did a little research. Instead of randomly trying to plug the gaps in my list of "required viewing" I tried a more scientific approach. I went over to icheckmovies.com, which has a dedicated list for most-mentioned films in famous best-of lists. Pretty meta, I know, but it does give you a good idea of what other people think are the must-see classics. The list is a little skewed (and limited by the lists icheckmovies.com thinks are appropriate), but I think it's one of the fairest sources available to determine the classic status of a particular movie. Bonnie and Clyde was pretty high on that list, yet I must confess that I hadn't really heard about the film before. I kinda knew about the "Bonnie & Clyde" saga, but even then the specifics were pretty blurry. A pretty good reason to catch up with this film.

Sadly I found Bonnie and Clyde to be a dangerously outdated affair. I won't contest the film's cinematic value upon its original release, but 45 years down the road very little is left of that. It's not entirely the film's fault I guess, Bonnie and Clyde follows a template that's been copied countless times since its release, but knowing that does little to make the sitting more enjoyable for us spoiled brats who watch it now for the first time. Everything the film does has been done much better since, which leaves only the story itself (also nothing to write home about I'm afraid).

Still, there were a few remarkable things. First of all I didn't have a clue I was watching a film with Gene Hackman in it until I checked the credits afterwards. That was quite the surprise. Then there is the local yokel soundtrack which is probably one of the worst soundtracks ever made and there is Blanche's character who oddly enough reminded me of the mother from That 70s Show. Safe to say she felt incredibly out of place. None of these things helped to make the film any better. The only positive bit was the ending, which was pretty over-the-top compared to the rest of the film.

I guess that if you're a die-hard fan of Mann's Public Enemies (which I hated too by the way) and you want to find out where it all began, Bonnie and Clyde still has some value, but apart from that this is a film that is pretty difficult to recommend. Time often isn't very kind to films that served as a template for others and 45 years is a long, long time.

Fanny & Alexander (dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1982 Sweden)

Winner of four Academy Awards including Best Foreign Language Film, Best Cinematography, Best Costume Design and Best Art Direction, the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film and the FIPRESCI Prize at Venice Film Festival

Bergman's Fanny and Alexander is a very interesting piece, theatrical and extravagant with a tremendous sense of both whimsy and wonder. The title's a bit misleading, given that Fanny has very little to do with the narrative. It's fair to say this is Bergman at his most autobiographical, and despite the radical changes in mood and epic running time, it may be his most accessible.

I chose the so-called "television" cut after much consternation, having had it suggested that to allow the 5 hour and 21 minute running time flow over the viewer was the best way to approach the film. I was rueing my decision during the early stages, but soon fell for its charms.

I see echoes of everything from the opening of The Godfather to Vinterberg's The Celebration in the family drama, as well as the likes of The Royal Tenenbaums or even Moonrise Kingdom. The theatrical staging, the Shakespearean motifs, and the arch drama all are clearly reflections of Bergman's own proclivities, a kind of summation of much of what he had done before.

The epic cut (which did play theatrically before its television premiere) finds time to really explore the characters in ways that, once things get moving, suitably create a thorough portrayal. The fact that the wiki page sums up this 300+ minute film in just a few paragraphs illustrates that plot is certainly secondary to the work. It's a film all about mood, monologues and the way both performance and character interact to create experiences for the audience.

At its core, it's not a particularly riveting film, but often I found myself captivated by a strident performance or a particularly beautiful composition. It played for me like Bergman's Barry Lyndon, without that film's narrative drive, but sharing a similar sense of pace and deliberate composition.

By the end, you genuinely care about how this crazy family gets along, shaking your head at the decisions many members make, but somewhat pleased that at least for some an escape to Stockholm may truly make for a better life.

It's certainly not the most challenging of Bergman's works, and it didn't move me in the way that The Seventh Seal's dark humour or Persona's shattering psychological take do, but I can certainly appreciate this work from an artist at the end of his road making a love letter to both an austere childhood and a wonderment in the world of puppetry, the theatre, and the use of magic in storytelling. Plus, the thing looks damn stunning and timeless on Criterion's Blu-ray, Svend Nyquist's Oscar for cinematography seems well deserved.

"Bergman is the only genius in cinema today", said an exacerbated Woody Allen, in his 1979 gem Manhattan. Pronounced with an assurance that echoes Allen's own well-documented thoughts on his cinema idol, he could not have known then that there would only be one more full-blown theatrical demonstration of such genius. Bergman would shortly announce to the world that he would be leaving his mistress, the Cinema: The uncharacteristically opulent and semi-autobiographical Fanny and Alexander would be his final film.

Putting an expiration date on his celebrated film career might've been Bergman's latest way of wrestling with "death" - something he's spent significant creative energy doing in the past. But Fanny and Alexander is no dour Scandinavian march to the grave. Such notions do play into the lovingly woven fabric of this tremendous project, as do elements of every other avenue of Bergman's life and career. But more than anything, this early twentieth century lavish omnibus is also a deeply personal salute to the life of the mind, namely, the imagination. Puppets, theater, performance, holidays, tradition, and mystery fuel the coming-of-age fire. Bergman cinematographer Sven Nykvist deservingly won an Oscar for capturing the mood of it all on film.

Although I'd managed to let the essential Fanny and Alexander elude me until now (shame, shame indeed!), I've seen enough of Bergman's work to know that he doesn't deal in cerebral chump change. His work is always unmistakably his, yet also always daringly adventurous, from the soul (if not always the heart), and packed with food for thought. "Life affirming", however, is one phrase that up until now, I would've struggled to apply to his filmography. With this absorbing swan song, Bergman leaves no stone unturned. Reality matters greatly here, but it's also a reality where seemingly anything can happen.

Young brother and sister Fanny and Alexander are eventually whisked off to the home of their abusive new stepfather, Bishop Edvard Vergerus (played with simmering aplomb by Jan Malmsjö). He is a terrifying and fearful man who wears his oversized cross as intimidation; wields his religious authority as a weapon. This is the type of character Christian viewers are understandably sensitive about being identified with, but Bergman's father was just such a man. Indeed, much of this film is lifted from the director's own childhood.

It's interesting that in the end, Bergman brings us to a place of promise amid the mortality. The hour of the wolf has passed, and the Reaper's gone on his way. (For now, anyhow.) And, although this really wouldn't be Bergman's final film, it stands nonetheless as one of the greats. (And that's just the shorter theatrical cut! Now all I want to do is make time to watch the full-length TV version...)

North by Northwest (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1959 USA)

Winner of the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Moton Picture, nominated for three Academy Awards, including Best Original Screenplay and Best Editing

North By Northwest was the only major Hitchcock film I hadn't seen. It's not like it wasn't on my radar or I was putting it off; it was just one of those things. So many movies, so much real life getting in the way. Which is why I love the ScreenAnarchy List of Shame. Turning a film's viewing into an assignment is a great excuse to bump it up to the top of the queue.

Right off the bat the film's got that old school magic. It's got a fantastic credits sequence/opening shot: a simple angled grid that gives way to traffic reflected in the windows of a Manhattan office building. An energetic Bernard Herrmann score that simulates the hustle and bustle of the city streets accompanies the image. Then there's the photography of the city itself, the Big Apple in the 50s, shot in glorious Technicolor. It ends with a great Hitch cameo, and a New York rite of passage: having the bus door slammed in your face. Then we're off, introduced to the oozing charisma and witty banter of Cary Grant, the George Clooney of his day.

It's Grant's immanent likability and chemistry with co-star Eva Marie Saint that propel this film. Once the machinations of the mystery are revealed, it is their relationship that keeps us intrigued. Watching them in action is a blast. I love how risque their mutual seduction feels, even after years of being beat over the head by unrepentantly raw films. It's a fine example of "less is more," although back then, some probably considered it too much.

Then there's the two now-famous action set-pieces. There's got to be an easier way to kill a man than sending him to the middle of nowhere and running him down with a crop duster, but it makes for some exciting Cinema. You can feel Hitchcock's giddiness as he tries to out-do himself with bigger and better. Combined with the climactic Mount Rushmore sequence, it helps elevate a simple case of mistaken identity into an action blockbuster.

What else can I say? Another shame successfully erased from my game! See you guys next month when I reach OT: Level 4.

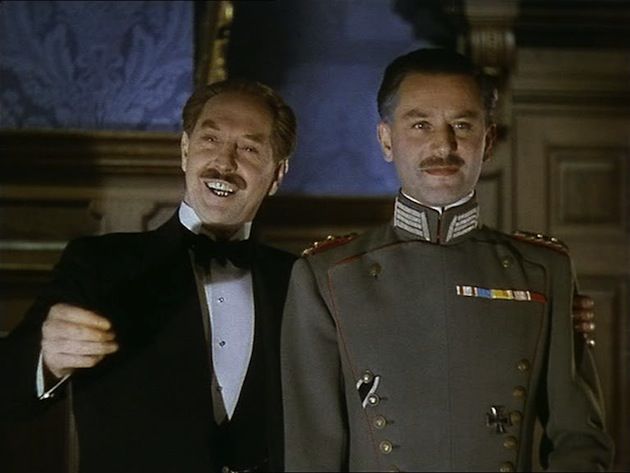

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (dir. Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger, 1943 UK)

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is an overstuffed, underdeveloped yet deceptively complex beast of a film. If today's long-form television existed in the early 1940s, it would make one hell of an HBO miniseries. The military career of Calvin Wynne-Candy reveals, in extended flashback, a number of insights into the British character and soul of the time. The first hour is a slog, but I have no doubt it will prove riveting second time around.

Viewers may take a while to get their bearings, but three hours later, the film has evolved into an immersive and compelling examination of shifting attitudes across generations and the true cost of war. That Blimp was made during World War II, featured a highly sympathetic German officer in a significant role, and is critical of Britain's "Total War" philosophy, is nothing shy of incredible. The very creation of the film remains an act of artistic bravery, recognised by Winston Churchill, who tried to have it banned.

An aging Wynne-Candy (a chameleon-like Roger Livesey) is one-upped by a younger officer on a training exercise, and caught with his pants down, literally, in a Turkish bath. The cocky lieutenant has no problem informing his spluttering superior that the rules of the game have changed. Flashback to a young, handsome and yes, cocky, officer Sugar Candy, making his own racket in the same Turkish bathhouse while on leave from the Boer War. After receiving word of rumblings of discontent brewing in Germany, Candy rushes down to play politics and gets mired in a gentleman's duel with officer Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff.

Anton Walbrook threatens to steal the picture ("Very Much!") out from under Livesey, just as his character steals the heart of Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr in one of three roles) from his rival. After their duel, the two officers spend time convalescing in a German hospital and become fast friends, which the film charts across the geopolitical adversity of both World Wars. In the middle of WWII, a retired Theo attempts to immigrate to Britain and gives a moving soliloquy on what has gone wrong with Germany under the Nazis. His heartfelt plea surely ranks alongside Chaplin's final speech from The Great Dictator.

Meanwhile, Wynne-Candy laments Britain as she threatens to lose her principles and moral superiority in order to fight the ever-escalating war against the Third Reich. As the picture finally catches up to where it began hours before, we can now begin to understand the semi-retired General Wynne-Candy. He is assembling London's Home Defence Force and sets up the ill-fated training exercise ("The War Starts At Midnight!"). At last the film lays an array of disturbing, yet high-minded, ethical cards on the table. But lest it be as dour (and sour) as Citizen Kane, Orson Welles' look at American capitalism and rot, Blimp takes another unexpected direction, acknowledging that society is doomed to change with the times. We must revere what made us great, but let go of the past if we are to embrace the future. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp took a satirical comic-strip character and fleshes him out into something much more. Damn if we shouldn't all be watching more Powell & Pressburger films.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (dir. Wes Craven, 1984 USA)

I'm not sure how, as a child of the 1980s, Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street went completely under my radar. But it did. Of course I've always known who Freddy Krueger was, that he murdered victims if they fell asleep, and that an embryonic, pre-21 Jump Street Johnny Depp got eaten by a bed. After having seen A Nightmare on Elm Street for the first time in my thirties, it's good to feel secure in my Cliff-notes-level rudimentary knowledge of the film (although, really, I still don't know who Freddy Krueger "is." Perhaps that's what the many sequels were for.)

I enjoyed A Nightmare on Elm Street more than I thought I would, which was surprising. That being said it is also frustrating, because I was hoping for it to be a lot creepier. I found the plot and set-up intriguing and the first two acts compelling enough. Heather Langenkamp (final girl "Nancy") is likably believable as a traumatized teenager, maintaining an even keel despite being put through the cinematic ringer (her repeated outbursts of "mother!" must have, no doubt, become incorporated into many a drinking game).

There were a few odd moments that struck me as silly and out of place, mainly having to do with Krueger himself. Specifically, there's a sequence with Krueger sporting clown-like, extended accordion arms in one of the kid's nightmares that was more strange than scary. I found myself longing to know more about Krueger and his personal history; the scene where "mother" explains Krueger's murder at the hands of vigilante citizens was not nearly as satisfying as it could have been, and had there been more exposition as to his motivation the overall creep factor would have been, for me, much higher.

There's an undeniable lightness about the film, much of which may come from it being dated (why can't Nancy just Google "Krueger"?) and not nearly as physically or psychologically violent as the horror films that make it onto my radar. Though it doesn't tread on the level of trope mockery and self-awareness to nearly the same degree as Craven's Scream series, it is also, oddly, less manipulative. Though there is a fair dose of blood and violence (enough that I could imagine it doing very well in a "mall" setting), it is far less frightening in its construct, with none of the startling jump-out-of-your-chair moments I was hoping for (and that still get me in Scream). As a series, Scream is so very predicated on Nightmare that it is surprising the former outshines the latter in this regard. Perhaps it is an improvement.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.