Blu-ray Review: MARTIN SCORSESE'S WORLD CINEMA PROJECT VOL. 2, A Trip Worth Taking

Martin Scorsese once again teams with Criterion to present six more important films in the history of World Cinema.

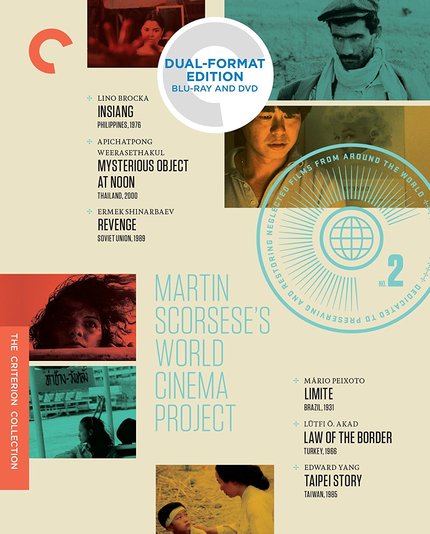

Nearly five years after Criterion released Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Project Volume One, an impressive box set of six films from around the world, we finally have its first follow up, Volume Two. Like the first volume in both packaging, added value, and format -- volume one arrived during Criterion's brief ill-fated foray into dual format releases, hence so is this set -- this is every bit the high falutin' hodgepodge that came before it.

This time, however, Criterion and the WCP have stepped up their game in terms of titles included. Several if not all the titles could've easily warranted isolated releases, which was not as readily the case with Volume One (a respectable set nonetheless).

Included this time are the following titles, each of which will be examined individually further into this collective review:

Insiang (Philippines, Lino Brocka, 1976)

Mysterious Object at Noon (Thailand, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2000)

Revenge (Korea, Ermek Shinarbaev, 1989)

Limite (Brazil, Mário Peixoto, 1931)

Law of the Border (Turkey, Lütfi Ö. Akad, 1966)

Taipei Story (Taiwan, Edward Yang, 1985)

Spearheaded by Martin Scorsese, he himself every bit a film historian and preservationist as much as a filmmaker, the work of the World Cinema Project is downright heroic. The goal has been to recover, salvage and restore important films from portions of the world that in many cases lack the means to uphold and maintain their own film heritage.

Bigger fish to fry, including but not limited to poverty, disaster, political shifts, and even war often result in important arts being neglected as the populace may well be in "survival mode", or worse. The World Cinema Project locates the best known film elements, and then races against time, decay and entropy to salvage the work for all time.

So often, even seasoned cinephiles in the "first world" are unfamiliar with such titles or even their filmmakers. These works, heretofore underrepresented, even as most have been underrepresented for legitimate external reasons, are potentially new discoveries for many of us.

This is Criterion, in their partnership with Scorsese's foundation, stepping out of their comfort zone of film school stalwarts, and turning the spotlight on the poor, the meek, the less fortunate. For the rest of us, it is to be received as an opportunity to get acquainted with such artists, their most important works, and by extension, the cultural time and place from whence they sprang.

INSIANG

"Why Insiang?", asks film scholar Philip Lopate in his printed essay on the film, included in the nicely sized book that comes with the set. (Other included essayists include Kent Jones, Fábio Andrade, Bilge Eniri, Dennis Lim and Andrew Chan, with an introduction by Abbey Lustgarten).

Fair question, considering, as the author details, its filmmaker, Lino Brocka, had an unbalanced career in terms of the quality of work he generated. Insiang, in some ways, seems to have risen to the top via process of elimination in the perhaps futile and pointless exercise of narrowing down Brocka's filmography to determine his best single work.

It is a powerful little fat-burner of a movie, reminiscent of the better-known World Cinema director that Brocka is most compared to, Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Both Brocka and Fassbinder operated concurrently, if geographically far removed.

Both utilized a shambolic yet colorfully pained reality of frustrated individuals hopelessly tethered to whatever locale milieu they were depicting at the time. Insiang, like Fassbinder's Fear Eats the Soul and so many others, bears that oily, grainy quality in the images themselves, leaving us with a kind of prestige grindhouse aesthetic. Finally, both Brocka and Fassbinder were said to have been gay, depressive, and unable to be cinematically prolific, at times to their own detriment.

Insiang opens with a brutal act immediately casting it into that increasingly dodgy category of real-life animal death films. The action of the leading male stabbing a pig in a slaughterhouse is bloody and unavoidable. It's also a character moment and mood-setter that's of course there for a reason.

Insiang is a young woman living with her mother in a dark and cluttered Philippine dwelling, abandoned by her father. Her mother is living the life of an aging lonely heart, luring optimistic men to her bed, and using the sound of running water to shield the sounds they make.

Insiang looks upon the resulting overflowing bath-sized basin with sad distain, it's wasted water representing so much squandered intimacy. She works hard to avoid falling into the traps and patterns of her mother, but with eligible young beauties at a particular premium in her area, how long can she keep the wolves at bay?

The film, while provocative and memorable, is a curious inclusion here, nonetheless. When one thinks "World Cinema masterwork", Insiang isn't the kind of work that admittedly springs to mind. All the more evidence then, perhaps, that the deep reaching goals of Scorsese's organization is about something other than that. Something more culturally nuanced, deeper.

MYSTERIOUS OBJECT AT NOON

Hailing from Thailand, all the way from the distant year 2000, we have still-rising filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul's Mysterious Object at Noon. To say it's an odd duck of a film is to both understate and overstate its sensibilities.

Being that it's a black & white experimental collage of people and daily life in Thailand shot entirely on 16mm reversal film, blown up to 35mm for maximum grain amplification, "odd" doesn't seem to go far enough in describing it. But if there's one thing it truly is, it is indeed a film.

Held together with the thinnest of narratives - something about a crippled boy who appears, cultivates some strangeness, and then leaves everyone else to try to make some sense of it all. But you can see it makes no sense at all. - Mysterious Object can be said to lack many things (regular characters, traditional scenes, a plot), but cinematic flair isn't one of them.

Turns out it's all an experimental art project, anyway. The resulting film is something intriguing but not engaging. Weerasethakul, recently out of American art school, took a skeleton crew all over Thailand, meeting people and asking them to improvise the next chapter in what may or may not be the plot of this movie. Then, he filmed some of the stories. The resulting tale is something as incoherent as it is fascinating. As a kinda sorta documentary/travelogue/experimental something or other, Mysterious Object at Noon is worth investigation.

REVENGE

Here we have the surprise extraordinary standout film of this collection. Kasekstan director Ermek Shinarbaev's third feature film is a revelatory discovery; a sumptuously haunting dream of a film. Dark and at times difficult, Revenge is nonetheless not an oppressive film, as one might've guessed based upon its packaging description.

A political metaphor that is too unsubtle to be missed, a tarnished sickle is handed down through generations, signifying the personal despair of the inescapable rage at the heart of the lineage's very being. It is the initial murder weapon that sets the tragedy in motion, hacking away the promise of art and specifically poetry in a rage of twisted violence. It is a meditation on how sin and darkness so deeply corrupts not only all people, but nations.

Made in the tumultuous era of the end of the Soviet Union, Revenge is indeed a masterpiece of a movie, one that tragically got lost in the shuffle. In telling an unpredictably unfolding tale of the cancer of human violence and revenge, Shinarbaev delivers an ethereal film, part ghost story, part veiled political protest, steeped in billowing fog and expertly blown-out lighting effects.

Yet, for all its directorial precision, Revenge is not an outwardly ornate film. Most of it unfolds in humble wooden shacks of 100+ years ago in a version of Korea that while realistically undeveloped, likely never existed. Without any access or knowledge of what the country was really like, director Shinarbaev happily admits to completely fabricating his version of old world Korea. It is, one must say, quite convincing.

Revenge, while not a "revenge movie" in the popular sense, strikes at the heart of the notion in ways that Tarantino and those he emulates only glimpse at best. Shinarbaev's Revenge is, as they should say, a dish best served by Criterion.

LIMITE

One will be immediately stricken by the filmic quality of Limite. (Or, if Criterion prefers a more concise term, "filmstruck"). A very rare 1931 silent film out of Brazil, Limite is first and foremost a kind of tone poem, a dwelling on nature, the finite in the face the watery expanse, and certain isolation.

Set in on the water in a small lifeboat, the cast is primarily two young women and a chained prisoner. Ostensibly, these are the survivors of some sort of disaster at sea. The film itself is far too internally oneiric to ever be so literal about what's happening.

What exactly is happening, though, doesn't seem to matter much. At times it bears the polarized brilliance of an Ansel Adams photograph, at other times, filmmaker Mário Peixoto's experimental flair veers into punchy student film territory. But more often than not, it's an effectively meditation with an elusive starkness in its visual quality.

Like so many of these films that Scorsese and company have saved, Limite brings with it a labyrinthine mythology of its own heretofore scarcity. In this case, there was only one very rare print, the single cinematic work of an artist director who spent the rest of his life milking its enigmatic status.

According to film expert Fábio Andrade's essay on the film in the box set's terrific bound sixty-page booklet, Limite was entirely out of circulation from 1959 to 1978, per an earlier restoration effort. Like any rare fruit of movie history, inaccessibility parlays into a legend of vitality. In keeping with this, Limite, despite and perhaps due in part to its scarcity, has assumed a reputation as one of Brazil's greatest films. Whether one feels it lives up to such promise or not, it's very good to have it around.

LAW OF THE BORDER

Hailing from Turkey circa 1966, Lütfi Ö. Akad's Law of the Border (aka Hudutlarin Kanunu) is something rather remarkable. As a tale of a parent in a desperate situation, it's drawn comparisons to De Sica's Bicycle Thieves, albeit with a lot of gunplay and land mines.

According to the essay in the accompanying booklet, the hard-bitten action genre was par for the course in the career of director Akad and the film’s star, Yilmaz Güney. When Güney, already an established action star approached the filmmaker for a collaboration, this weighty, nuanced ponderance was likely not what he had in mind.

The black and white film is daftly made of also evidencing a lack of production resources. It might take some warming up to, but once the viewer falls into the groove of Law of the Border, the experience of watching it becomes tremendously rewarding.

Gunfights and tough guys abound as a perilous trip across the restricted border territory becomes the mission of the day. It's the kind of war torn lunar surface where unsuspecting donkeys are made to drag small felled trees across the fields as a means of land mine detection. Not exactly the sophisticated height of battlefield technology, but this is Turkey amid political chaos - something sadly none too rare for the country.

The star Güney went on to become a political revolutionary in his own right before his death in 1984. He remains an iconic and controversial figure, his image symbolically persevering. Finally, this important piece of political entertainment is also preserved. The condition of the print itself is highly compromised, the most damaged film in this set. Sadly this is what we're left with. For decades, Law of the Border was thought lost. Miraculously, its crossed over into widespread availability.

TAIPEI STORY

The second film by Edward Yang (Yi Yi; Brighter Summers Day) 1985's Taipei Story demonstrates an extraordinarily keen sense of framing and cutting - the two very foremost aspects of motion pictures that are capable of rendering them "cinematic".

At two hours in length and focusing primarily on a thirtysomething couple (played by Yang's first wife Chin Thai & fellow acclaimed director Hou Hsiao-Hsien) trapped in a nebulous zone of their relationship, one could make an argument that this is a movie where nothing, or very little, happens.

In a sense, that's correct. But also in a sense, it's completely wrong. Just as our lead couple is steeped in a transitional malaise they can't pinpoint, so too is the entirety of their immediate outside world. Hou, interviewed recently for the disc's supplemental feature, states that his late friend and filmmaking compatriot Yang was interested in exploring the clash of what's old and what's young in their country at that time.

But for this viewer, having just viewed the film for the first time, Taipei Story seems to be more about what's here (there, in mid-1980's Taipei) and what's elsewhere, and more specifically, what's native and what is intrusive. Is Western culture's intrusion a nefarious thing? Or does it just mean more baseball and fast food? Such looming considerations come and go, but the lethargic melancholy of the characters' lives remains front and center. Taipei Story is far from a happy film, but it's the kind of unhappy film that is so vibrant and alive at its core, it is never not also invigorating.

In his brief video introduction to the film, Scorsese proclaims that Taipei Story is evidence of how Yang never wasted a second of his films. Sounds like pure hyperbole, but he's really correct. As title invites the comparison, Yang's film, like Ozu's Tokyo Story before him, reveals the soul of the place of its title while intensely focusing on a set group of individuals. Their interior lives nor the interior of their homes may be all that appealing, yet the film is, in every way.

*****

A most curious blend of first films, acclaimed films and only films, Martin Scorsese once again has steered his World Cinema Project to a winning collection with Criterion. It is an honor to review their efforts, as, all in all, such a shining package gives a greying cinephile hope for the future of global film restoration, and a tremendous look at some of the great, recovered film art from corners of the world in periods that one didn't even know films were being made. On a greater level, it is through exposure and consideration of films such as these that truer understanding of the humanity of those we might consider "other" can occur, in one evening, in your own living room.

Each film includes a recently produced interview segment with one or two people in the know about it. They tend to run about eighteen or so minutes, and are of course helpful in getting to better know these films. Also helpful are Scorsese's individual introductions to each film, even if his earnestness sometimes goes down as over-dialed.

An undeniable upping from WCP1 in terms of titles and filmmakers included, Criterion's World Cinema Project Volume 2 is, without question, a global voyage worth taking.