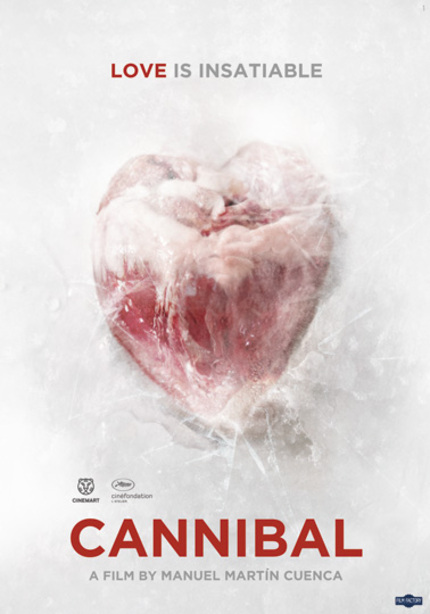

TIFF 2013 Review: CANNIBAL, A Beautiful And Minimalist Study Of Love

But rather than take a melodramatic, religious, or psycho-killer approach, director Manuel Martín Cuenca's Cannibal is a minimalist thriller, a story of love and pain, stripped of veneer and yet controlled and refined. It is a film about light and shadow, the interior and exterior spaces we occupy, with a incredible central performance by Antonio de la Torre.

De la Torre plays Carlos, a tailor of men's suits who lives a relatively isolated life in Granada. He is also a cannibal, killing young, foreign women with few ties who cross his path, taking them to his cabin in the mountains, preparing their meat and eating, mainly alone, in his small flat. After he murders and eats his Romanian neighbour, her sister, Nina, inquires after her whereabouts. Despite himself, Carlos begins to help Nina, and a strange romance begins.

The reasons behind Carlos' gastronomic interest are never really explored; but then, do they need to be? The actions are far more interesting than the motivations, at least for me in watching, as de la Torre held my attention from start to finish. Carlos takes the same pride in his dissection of the human body (again, never seen, which is to the film's credit) as he does in tailoring. There is a detachment form both, as if it is only through detachment that he can survive. De la Torre shows Nina's growing affect on Carlos through small gestures, the movement of hands that hesitate, or words uttered so slowly and quietly as almost to be missed.

But it is in this minimalism that the film must be, for lack of a better work, read. Cuenca has stripped the film of any grand gestures. Instead, a formalism within simplicity is there. There is no score, what little music there is is diegetic, and Cuenca instead works mainly with either the natural light of the sun, or those lamps that would naturally fill a space. One shot of the city at dusk shows it as a blaze of red, and if the blood that Carlos has spilled somehow infects it. The camera moves only when necessary; frequently remaining in one position for an entire scene, moving only to show necessary close-ups or shot/reverse shot. It is almost as if the camera is reflecting Carlos, considering every sound and gesture, and taking the audience through all these considerations, to understand how to act with such cold precision.

But this coldness is challenged by Nina, and the play of shadow and light. She is as much a mystery as he is; each of them moves cautiously in the various spaces, trying not to risk exposure, though Nina (out of necessity) reaches out to Carlos, and draws him to her, metaphorically and literally. And the spaces are frequently tight, whether that comes from walls or darkness. With little room to maneuver (and in the case of Carlos, little room for mistakes that might draw attention to his crimes), each slowly circles the other, admitting little by little of their situations and lives (or at least Nina does; Carlos takes more prodding).

The few outdoor scenes move between the warm beaches and the cold mountains, what Carlos could have and where he chooses to return. As he grows closer to Nina, he slowly inches towards the light, but Cuenca always keeps shadows at the edges, reminding the audience of that darkness in Carlos' heart. Cuenca gives us a meditative examination of the strangeness of this particular human heart, without resorting to cheap violence, but instead presenting a meditative study in precision, pain, loneliness and redemption.

De la Torre plays Carlos, a tailor of men's suits who lives a relatively isolated life in Granada. He is also a cannibal, killing young, foreign women with few ties who cross his path, taking them to his cabin in the mountains, preparing their meat and eating, mainly alone, in his small flat. After he murders and eats his Romanian neighbour, her sister, Nina, inquires after her whereabouts. Despite himself, Carlos begins to help Nina, and a strange romance begins.

The reasons behind Carlos' gastronomic interest are never really explored; but then, do they need to be? The actions are far more interesting than the motivations, at least for me in watching, as de la Torre held my attention from start to finish. Carlos takes the same pride in his dissection of the human body (again, never seen, which is to the film's credit) as he does in tailoring. There is a detachment form both, as if it is only through detachment that he can survive. De la Torre shows Nina's growing affect on Carlos through small gestures, the movement of hands that hesitate, or words uttered so slowly and quietly as almost to be missed.

But it is in this minimalism that the film must be, for lack of a better work, read. Cuenca has stripped the film of any grand gestures. Instead, a formalism within simplicity is there. There is no score, what little music there is is diegetic, and Cuenca instead works mainly with either the natural light of the sun, or those lamps that would naturally fill a space. One shot of the city at dusk shows it as a blaze of red, and if the blood that Carlos has spilled somehow infects it. The camera moves only when necessary; frequently remaining in one position for an entire scene, moving only to show necessary close-ups or shot/reverse shot. It is almost as if the camera is reflecting Carlos, considering every sound and gesture, and taking the audience through all these considerations, to understand how to act with such cold precision.

But this coldness is challenged by Nina, and the play of shadow and light. She is as much a mystery as he is; each of them moves cautiously in the various spaces, trying not to risk exposure, though Nina (out of necessity) reaches out to Carlos, and draws him to her, metaphorically and literally. And the spaces are frequently tight, whether that comes from walls or darkness. With little room to maneuver (and in the case of Carlos, little room for mistakes that might draw attention to his crimes), each slowly circles the other, admitting little by little of their situations and lives (or at least Nina does; Carlos takes more prodding).

The few outdoor scenes move between the warm beaches and the cold mountains, what Carlos could have and where he chooses to return. As he grows closer to Nina, he slowly inches towards the light, but Cuenca always keeps shadows at the edges, reminding the audience of that darkness in Carlos' heart. Cuenca gives us a meditative examination of the strangeness of this particular human heart, without resorting to cheap violence, but instead presenting a meditative study in precision, pain, loneliness and redemption.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.