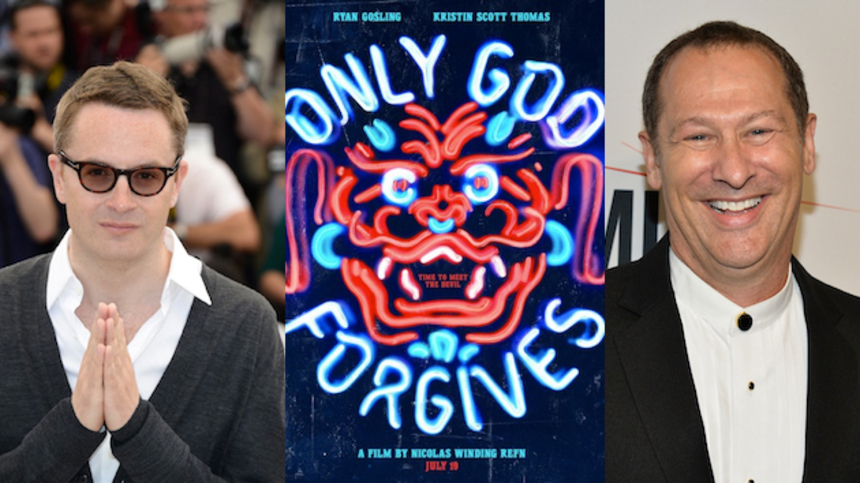

"Ask Not What Art Is, But What It Is Not": Nicolas Winding Refn And Cliff Martinez On ONLY GOD FORGIVES

Though I took to the film immediately, it actually took me two viewings (the second was the next night back in LA at the LA Film Fest) to declare it to be Refn's first masterpiece, because thirty years from now when we talk about movies of the early 21st century, Refn and Only God Forgives will undoubtedly be an important part of that conversation. That may sound like absurdest hyperbole, but this is coming from someone who has taken a very long time in warming up to Refn's macho pop-opera filmmaking. No, it's not Drive 2: Bangkok Bugaloo, and in many ways it isn't even Ryan Gosling's film. Only God Forgives is an expressionistic eastern-western that crashes the gateways to both heaven and hell. It's a repulsive, visceral and equally very spiritual film that asks its audience to not shut down, to stay aware, to look beyond its stylized violence and brooding, calculating characters. It asks us to look deep within ourselves, within human history, and by reflection cinematic history. To be repulsed by this film is to react, and thus, be awake. Refn is here to wake us up.

Vithaya Pansringarm as Chang, the all-powerful Thai police lieutenant, wielder of one bad-ass blade, and lover of karaoke, is, if you ask me the real star of the film. Discussion on both the symbolic and practical constructs of his character make up a good chunk of the following conversation, which focuses solely on this film (for more on Refn's next projects and other anecdotes look out for James Marsh's interview later this week). While we do not discuss the story of the film in detail, we do explore in-depth its themes and symbolism around religion, masculinity, motherhood, power and submission. So be warned, as certain kinds of thinkers may find spoilers ahead if they have yet to see the film.

The other side of the conversation relates to Martinez's dynamic score and his relationship with Refn and sound designer/sound editor Kristin Eidnes Andersen -- enjoy!

ScreenAnarchy: So just to let you know I will from time to time be looking at my notes as I find myself in the interesting position of having seen the movie and now only half an hour later sitting down and talking to you both about it.

Nicolas Winding Refn: What was your first instinct? What was the first thought that came through your mind?

As the lights came up a rather complex thought occurred, which was about the architecture of the film. This generally happens every time I watch a film of yours. It's not only the larger thematic and symbolic architecture, but also the ways you frame within the frame half a dozen times. So the architecture of this one to me, because I consider the film to be largely an indoor western, was interesting from a sense of space. Not only of the image, but of sound. In the case of the image, we have the main hallway that Ryan Gosling's Julian often travels through, you know with the flames of hell and all. And then there's the nature of where and how the sound is moving through that space too, which is often ambient and moody. Overall it's like a slow-motion, or near motionless opera.

Now, Cliff, you mentioned earlier that you had read the script early on in Nicolas' process. How early on did you two then come together and begin to discuss the music?

NWR: Well we had to start with some of the karaoke songs pretty early, so we were already doing some recordings before we started shooting to have it ready for the shoot itself. Through that there came the whole introduction to Eastern music, especially using the Thai take on country western music. And then we went off and did the movie. We then started editing it with the intention that this film was gonna have a lot of music. We had some temp tracks that helped us set the mood. And then once we got closer to locking the movie, once we found the structure of the movie, it was time to hand it over to Cliff.

Cliff Martinez: Unlike Drive I was kinda brought in at the ground floor with this one. At the script level we were in contact and then right after shooting, and of course there was the karaoke stuff. But my process usually doesn't start until I see something. So I saw a rough cut with the temp music, which was Bernard Hermann's score for The Day The Earth Stood Still, which is actually my favorite film score. I then spent a week at least just lying on the couch, staring at the ceiling, just trying to figure out what the film was going to sound like. Because it's not going to sound like The Day The Earth Stood Still. It's a partial idea, but you can't make it sound like a 50s sci-fi film, and anyway I'm not capable of that even if I wanted to. So I began to ask what are the elements of that... that are useable... that are important to the dramatic function of the music? I spaced for a week or two...

It was that meditative process. You had to let that open up and sit with it.

CM: Right. I think I had a couple of sketches. Nicolas was in Los Angeles shooting a commercial and so he came over to the house and we listened to some of it. I think that was the one and only time we sat in a room together working on it.

NWR: But even that was like five minutes.

CM: Yeah, it was very brief. But that is how the process usually begins and then I get feedback from him, and I start writing more stuff. It's then sculpting and refining.

There are so many tones to the score, so many moods and shades to it. There was the one queue that reminded me of Bernard Hermann. Right away I perked up and recognized that influence, and was very delighted by it.

CM: Oh, I'm glad it's discernible.

The journey into this Thai folk music and its history, really getting ingrained in that, must have been important even if it didn't end up in the forefront of the actual score.

The journey into this Thai folk music and its history, really getting ingrained in that, must have been important even if it didn't end up in the forefront of the actual score. CM: Well there's probably more to it than you think. The Thai Pin is probably in four of the queues in the film, and that's me trying to play a Thai folk instrument in the correct style, and failing to do that, but coming up with an interesting result. To me that instrument lead the way for one of the important Chang themes. I think to a degree we relied on a few old tricks too, which are some of the ominous, ambient textures.

I kept hearing echoes of George Crumb in a lot of the ambient stuff. So while the score consistently reminded me of all these other musicians like Hermann and Crumb, it was the fact that it was honoring the legacy of those musicians that made it feel equally fresh. In that way the film itself, sans the score, holds with it a very obvious legacy of the filmic medium too. I look at all of your films Nicolas as building from the mythology of cinema, the fairy tales as it were. In someway "Drive" was a super hero film, and "Only God Forgives" is more than a bit of a western. Here it's as if Powell and Pressburger made a Suzuki Seijin movie. There's this melodrama that wants to leap forward but it gets sidelined, then slowed way, way down. As you stated at the Q&A, it's like an acid trip. [note: Refn also stated to the audience twice that he had never taken drugs, nor did he drink alcohol.]

NWR: It's true.

Chang is supposed to be the God of the title, but also the symbolic father figure.

NWR: He is a figure of fantasy in that it's a fetish orientation. In the sense that God in the Old Testament is saying "I can be cruel, you have to fear me" as "I can be kind, you have to love me."

Every time Chang goes to sing karaoke I saw two things happening: He lulled the room into submission, commanded this room filled with police officers. At the same time the karaoke was a way for him to cleanse himself of all these acts he was committing.

NWR: Well through music, through sermon and a very classic way of sining, you cleanse your soul and cleanse your sins. You purify yourself. And yet there's also something very much like the priesthood about Chang and what he does. You're giving a speech..

...To your disciples...

NWR:.. To your disciples who worship you unconditionally.

The relationship that was developing between Julian and Chang... it very much felt like there was this need for Julian to have Chang's acceptance.

NWR: Submission to any religion is you giving up your identity. And especially for men, taking away their fists and their arms, handicaps them because that is very much what we rely on. And there's a fetish there... this to this...

The open palm compared to the closed palm...

The open palm compared to the closed palm...NWR: Right, because the closed palm almost looks like an erection.

CM: It looks a lot like my erection, if I'm being honest.

[A good amount of laughter from all of us]

One thing that folks often find so striking in your movies is the way color is used. Though this is usually on the cinematography side of things. "Only God Forgives" is certainly no exception, but There's something in here with the costume design that I really liked. You have Julian wearing a black t-shirt, and then sometimes a white t-shirt (usually when he's having visions), and then you have Chang wearing his uniform. It's black, but with the white collar. And that right away queued me that they were connected, not just through the visions that Julian was having of Chang before he actually saw him. There was a sense that they were cut from the same cloth.

NWR: Well there's a thread of morality. Chang's way of life is "you are the consequences of your actions and nothing ever goes unpunished."

Chang is a cleanser in that way. In the Q&A you described Julian's mother [played by Kristin Scott Thomas] as kind of a devourer. Is Julian a pawn between this cleanser and devourer? Where do you place him?

NWR: He's a sleepwalker. Because he walks through life not knowing what he is moving towards. But because of his condition he is forced to walk as if he is asleep. So it's like in the world of the dead. He's cursed forever. He's chained to his mother's womb. How he can release himself is to go back into the womb.

The womb image is my favorite in the movie, because it was absolutely, immediately literal, in what he was doing, in encountering his origin like that -- and his understanding it.

NWR: Yeah, it's like a wake up call.

It's a rebirth in someway.

NWR: But to be reborn, one must enter what one came from.

Thinking about sound again... one example that stood out to me, in regards to how sound design and the music can work together or allow each other space, was the foot chase after the shootout at the restaurant. Cliff, what kind of communication was going on between you and sound designer/sound editor Kristian Eidnes Andersen?

CM: I was in close contact with Kristian because a lot of things overlapped. To me the definition of sound design... from a sound editor's point of view... is that if it's pitched, that's me, and if it's not pitched, that's you. Some of the stuff I do that's pitched is very sound desinger-ly in nature. So we really had to communicate a lot to understand each other's way. But in that particular scene my impulse was to do the expected thing, which was: let's hear some chase music. And Nicolas feels the same way about chase music that I do: It's really predictable so most people kind of get too comfortable with it.

NWR: I definitely think there was a collaboration, because when you deal with music in a movie that has very little dialog, sound and music become very useful tools. They will automatically overlap. And this was something that we brought up from the very beginning in that, "who does what?" We had some really good discussions from the beginning saying, "well, you're gonna try this and I'm gonna try that over here. And then we'll see..." Sometimes Cliff and Kristian would counter each other in the mix. We would then remove one, or keep both, or mix them together.

And in that foot chase, ultimately the music took a step back...

NWR: In an action scene like that it usually means music, but I like the sound of the feet.

That's the rhythm, kind of like the heartbeat...

NWR: Right, so it's about sustaining that.

CM: Nicolas did that a lot in Drive too. Consider that one scene where he drives back. That would be the standard place to put the music. Or in the elevator. And Nicolas had music either before or after that, because I think it was more interesting to score the calm before the storm or right after the storm. You leave the storm itself alone.

There's that danger with a lot of films to over score, but then there are those films where the score absolutely embodies the essence of the film. I think that's what's happening in OGF. It ultimately acts as the spiritual signatures for these characters. I mean everyone is so shut down, but so focused at the same time, so there's the music aligning things on the spiritual level, since you are talking about the gateways between heaven and hell and the very practical, tangible world. I suppose that music-wise the Eastern influence which remains strong in the film are the percussion and the horns, which to me are very spiritual.

There's that danger with a lot of films to over score, but then there are those films where the score absolutely embodies the essence of the film. I think that's what's happening in OGF. It ultimately acts as the spiritual signatures for these characters. I mean everyone is so shut down, but so focused at the same time, so there's the music aligning things on the spiritual level, since you are talking about the gateways between heaven and hell and the very practical, tangible world. I suppose that music-wise the Eastern influence which remains strong in the film are the percussion and the horns, which to me are very spiritual. CM: If you sense any kind of spiritual or religious quality in the music then mission accomplished. I mean the movie is called Only God Forgives after all. But some of the hugeness, the bigness of the drums, the sound of the orchestra... and the pipe organ in particular was another element that was intended to evoke a religious quality. If you hear that then that is good. As I moved away from it I lost a sense of that, which I'm only now getting back in talking about it.

I do personally associate a lot of those sounds -- the drums and horns -- with spiritual practice, with meditation. So to have it present in a world of such violent contrasts... it's actually very liberating, it's very freeing. It allows us to go into the movie and consider... to be repulsed by some of these violent things that are happening, but to not turn ourselves off and step out of the movie and not appreciate what's happening there. Nicolas, do you find that at the end of the day, you want to start a conversation with the audience more than anything. That it is a back and forth, a cycling and mirroring of ideas...

NWR: Sure. And the idea that film as an experience is a two-way concept. It can't just be one way, because that'd be one note, and therefore it has to be a cycle that has to start between an audience and what they experience. Whether that's music or literature, museums, film, it doesn't matter. But it's almost out of respect for an audience that you set it up like this, because there's a notion that we live in a society that we very much define our entertainment on a scale of whether it was good or whether it was bad. It's a very strange concept to describe something that essentially speaks to our emotions as just being good or bad.

It's black and white thinking.

NWR: Not only that, it's very much how we are taught or told how to view entertainment or art most of the time. But I have this theory, which is of course art is much more interesting if you don't ask what it is, but you ask what it's not. Because when you ask what it's not, you then force yourself to actually answer it in someway.

You're not closing the door either. The inquiry is there, and you remain curious...

NWR: All the way through. And you will continue for the rest of your life, because everyday that experience is different. So if you ask it again "what are you not?" then everyday there is a new answer. Where as if you ask what it is, there's an immediacy for a response so you can move on. But why would you want to merely move on when you just spent two precious hours of your life experiencing something.

---

As I get up to depart for the hotel, the ice cream and chocolate chip cookies Refn had ordered long before our conversation started finally arrive. I smile and say to him, "Ah, so you don't drink or do drugs, but you do have a sweet tooth." Refn nods back: "Exactly."