Gamera Obscura: The Best Five Minutes of THE PURGE: ELECTION YEAR Are Clichéd and Nonsensical

One of the many reasons I’ve never been terribly successful as a movie reviewer is that I tend to confuse “interesting” with “good.” Consistent with that, yet worse still, as in the case of The Purge: Election Year, is that I’m likely to find a movie’s most incoherent, contradictory, or unbelievable moments its most strangely compelling.

Of course one could argue, and plenty of critics have, that the very premise of James DeMonaco’s Purge films is absurd, not just select moments. Twelve hours of legally sanctioned carnage every year? Um… maybe. I guess everything depends on where you go from there, both in tone and the world-building you do around such a premise. Consider Death Race 2000, Battle Royale, The Hunger Games.

For me the most ludicrous element of The Purge universe is quasi-ideological -- that the moneyed classes would promote property destruction when they’re the ones who own all the property; after all, that’s kinda how capitalism works. (I had a similar problem as a literal-minded youth watching Escape from New York, but the silliness of turning some of the most valuable real estate on Earth into a penal colony was mitigated by Carpenter’s exuberant imagination and command of the symbolic.)

Unsurprisingly, then, political incoherency runs throughout The Purge: Election Year. We get laugh lines that rely on sexualizing Elizabeth Mitchell’s character and leveraging racial stereotypes at the same time a self-consciously diverse group of heroes is shoved at us. We get textbook examples of both the “good” immigrant and frothy xenophobia. A defender of DeMonaco’s script might claim that it tries to go beyond simple binaries, but to me it’s more a case, as it usually is with Hollywood product, of providing something for everyone -- of a movie having its cake and scarfing it down, too.

Similarly, critics are apt to recoil when they detect this same self-indulgent yet self-righteous approach to the flamboyant violence that drives the franchise. For example, here’s the always-smart, always-readable John Semley writing in The Globe and Mail:

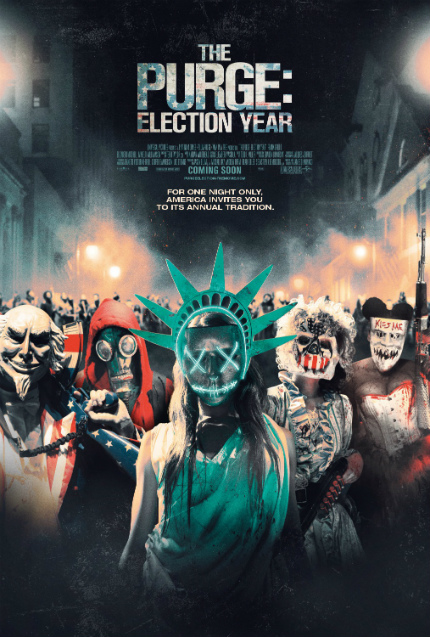

It would be one thing to bait the viewer’s blood lust and then punish them for it. But the films command an audience that’s enchanted by its displays of blood-drenched yahoos in kooky masks satisfying their barely repressed psychopathy. Judging by the series’ not-unremarkable box office returns, and the cackling and clapping gallery at the recent midtown Toronto press screening, such a viewer is in no short supply. The problem with the Purge films is they feel like they’re made for people who would actually take part in the purge.

I think Semley is getting close to the heart of the matter here, but stops just short of revealing the unpleasant truth that’s evident in the film’s most over-the-top sequence. (Oh, and before I forget, this column will always be drenched in spoilers, so be warned.)

I’m referring to the sacrificial sequence that takes place in one of George Washington’s favorite churches. Despite the neat casting of Kyle Secor as the "minister” -- the overlap of the governmental and clerical senses of the word underscore the civic religion theme -- and the way we can picture him as a latter-day incarnation of Tim Bayless’s lapsed Buddhist, everything plays out as a massive genre cliché. Without any apparent shame, DeMonaco trots out all the trappings of a ‘70s occult/devil-worship flick, minus any style or camp, not to mention suspense. All we’re missing is the dark robes, Latinate incantations, and salacious nudity.

Yet the scene still works.

Or rather, it does if you churn it over in your head a bit. Perhaps that's because we dimly realize that what’s happening is in some way truly religious. For starters, it might register that the date of the Purge, were it to have actually taken place in 2016, occurred at the start of Holy Week, just following Palm Sunday. And of course all of Secor’s altar-launched speechifying about atonement through another’s death both invokes and evokes the Passion.

Moreover, the way that the scene self-presents as private worship, away from the media and the public, undermines the concept of the collective Purge as a mere cover story for class warfare: these crazies, it becomes clear for the first time in three movies, really believe this stuff. They just want to get all the bloodlust out of their systems so that they can return clear-headed to their office jobs the next day. Is that too much to ask?

In this light, it may occur to us to wonder just who is this God to whom they’re all praying. Sorry to say, but I think that’s us -- the great Unknowable Audience that surrounds them, all-seeing yet invisible, in that church. We’re the ones who, through emotional/ethical allegiances and by familiarity with genre tropes, are mentally “choosing” which characters will live or die. The narrative itself is a bit nonsensical in this regard as the worshippers treat their victims alternately as honored martyrs or rivals to be eliminated for mundane political reasons.

So when Semley speculates that certain moviegoers might participate in an actual Purge, my response is that in a sense we already do -- it’s called going to the movies. We’re the ones who long to witness artful and exciting killings though, of course, the movies we prefer must first dodge the superego’s protests: solid moral frameworks are the prerequisite to allowing the id to rampage.

The end result is the same, though: catharsis. The country club sadists in that D.C. church indulge but once a year; we genre enthusiasts, and exploitation fans in particular, we indulge every time we go to the cinema. And no, it’s not a bad thing to hold a mirror up to the audience once in a while and keep us honest -- it would be nice, though, if it weren’t so smudged with dirt that we can barely see ourselves in it.

Gamera Obscura is a column about the ill effects of seeing too many movies over too many years. Peter Gutierrez also writes the Blockbuster Central column for Screen Education, and can be hunted down on Twitter @suddenlyquiet.