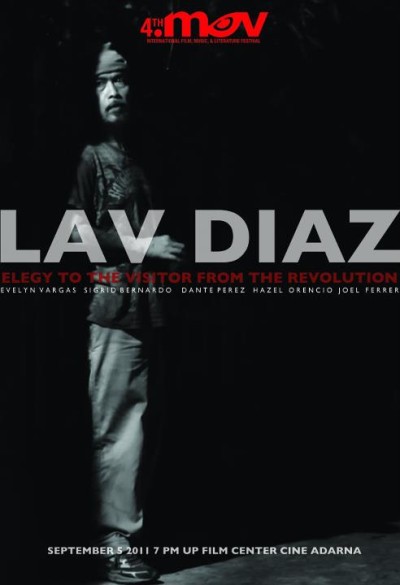

ELEGY TO THE VISITOR FROM THE REVOLUTION Review

-thumb-430xauto-25617.jpg)

Originally

planned as a one minute short for Nikalexis.MOV,

a program of short films dedicated to the memory of slain critics Alexis

Tioseco and Nika Bohinc that featured short works by directors like Raymond

Red, Rico Maria Ilarde and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Lav Diaz's Elehiya sa Dumalaw mula sa Himagsikan (Elegy to the Visitor from the Revolution)

grew both in length and concept, turning into a film that is ponderous and

perplexing but is still grounded on very familiar emotions of melancholy and

despair. It is undoubtedly a film that sprung from spontaneity, with Diaz

literally writing the film as he was shooting it with a cast of actors and friends

who are willing and ready to take in complex roles in a very short period of

time.

Walang Alaala ang mga

Paru-paro (Butterflies have no Memories, 2009),

Diaz's one-hour meditation on the moral and environmental changes in an

abandoned mining town in the island of Marinduque, is evident in its struggle

to communicate the spare and pained aesthetics that Diaz is most famous for

within an hour. As a result, the film feels unduly hurried, rushing to arrive

at its beautiful conclusion. On the other hand, Elehiya sa Dumalaw mula sa Himagsikan, despite clocking at only one

hour and twenty minutes, is deliberately structured and less beholden to its

narrative. The film is told in three parts, with each part pertaining to each

of the three visits of the time-travelling visitor from when the country was

fighting for independence from Spain.

The

three parts are themselves divided into seemingly incongruent storylines. A prostitute

(Sigrid Bernardo) patiently waits for a customer. A musician (Diaz) plays

various melodies for nobody. Three petty criminals (Dante Perez, Evelyn Vargas,

and Joel Ferrer) are preparing for a heist. A woman (Hazel Orencio) from the

country's past suddenly appears in a busy marketplace, venturing then to fountains,

rivers and other watery places. The storylines eventually converge, revealing

characters whose lives are consumed by desperation, forcing them to venture into

territories that compromise relationships and whatever remains of their

fractured humanity.

Clearly,

the prostitute and the petty criminals, with their botched attempt to drift out

of their sorry lots, are only victims of a country that has sadly devolved from

what it was originally intended to be by the revolutionaries who risked lives

for freedom. Diaz does not create characters that are evil by nature. Like the

trio of kidnappers of Walang Alaala ang

mga Paru-paro, the ox-cart driver of Heremias

(2006), or the displaced farmer and miner of Ebolusyon ng Isang Pamilyang Pilipino (Evolution of a Filipino Family, 2004), his characters are drawn to

extreme actions naturally by an evil society, corrupted by systems that have

remained unchanged or adopted through several years of abject complacency or

lack of identity.

In

one of the rare close-ups in Diaz's entire filmography, the visitor from the

past directly looks at the audience, her face aching with heavy emotions of

regret and sadness, the same regret and sadness that pervades the musician's

solitary strumming. It is a hauntingly beautiful dream sequence, unsettling in

the way it directly confronts with images bursting with the most wistful of

emotions. Dreams are said to be products of unprocessed memories. The dream in

Diaz's film seems to be the product of a nation's unprocessed memories,

burdened with a decades' worth of tireless but unmerited struggles.

Elehiya sa Dumalaw

mula sa Himagsikan is

clearly Diaz's lament to what the country and its citizens have become. More

importantly, it is also his ode to those who continue with the revolution,

notwithstanding their songs being unheard, their images being unseen, and their

impassioned calls being unfelt. It is everything Diaz stands for. It is

everything Tioseco stood and wished for.

(Cross-published in Lessons from the School of Inattention.)