WHEAT review

The Battle of Changping was one of the decisive military engagements between the rival dynasties of Warring States period China; it all but wiped out the losing side, and still ranks as one of the deadliest confrontations in history. With that background Wheat might seem like another tired battlefield riff on heroic bloodshed at first glance, coming as it does after a run of (for the most part) rapidly diminishing returns as one director after another tried to jump on the high-concept wuxia pian gravy train post-Hero, House of Flying Daggers et al.

But Wheat isn't about the conflict itself, and He Ping has never really been about that sort of film. The veteran mainland director already had one shot at mainstream overseas success with his last film, Warriors of Heaven and Earth (2003), and for all the funds that went into it and the A-list pan-Asian cast the result was an uncomfortable mishmash of popcorn genre tropes that never quite took off.

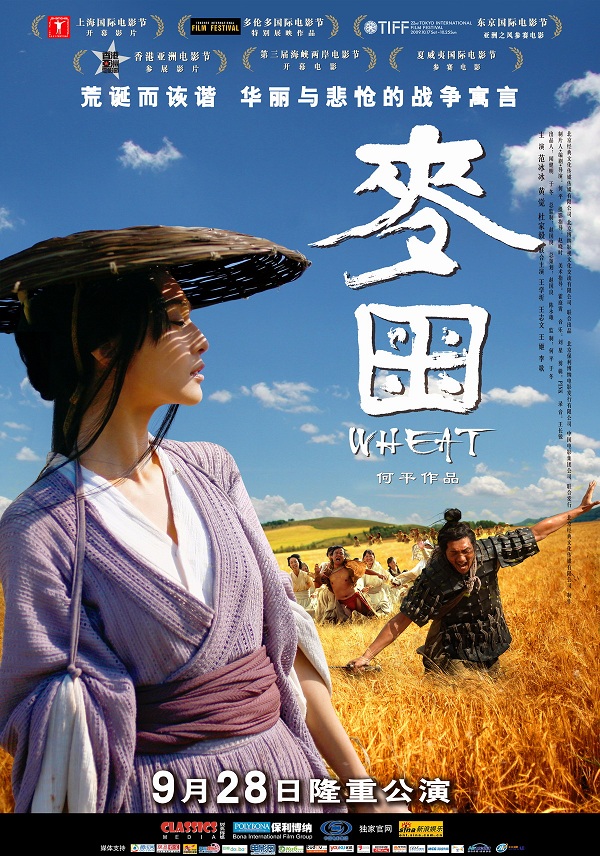

Wheat is far simpler, almost classical, recalling the director's earlier films (particularly his cult 'Chinese westerns' Killer In Doubleflag Town (1991) and Sun Valley (1995)). Two deserters from the victorious Qin army, an elite warrior (Huang Jue) and a simpleton (Du Jiayi), flee the aftermath of Changping and end up washed up on the riverbank close to a tiny walled settlement in Zhao country.

The ruler and all his men over twelve years old have long since marched off to war. The women keep the town going in their absence under Lady Li (Fan Bingbing, Sophie's Revenge, Shinjuku Incident) - wife of the departed Lord Ju Cong - anxiously waiting for any news from the battlefield while they get ready for harvest time.

The two soldiers manage to pass themselves off as messengers in advance of an official proclamation Zhao were victorious but as time passes and a bandit leader arrives with his raiding party (Wang Zhiwen, The Message, Gimme Kudos), it's anyone's guess as to how long the deserters' story will hold up under further questioning.

While there's no lifting from the classics outright (The Banquet), overt theatricality (Curse of the Golden Flower), or even any element of camp (The Promise) Wheat is still a very stately, measured film that draws from stage performances and Greek tragedy far more than it apes the manufactured exoticism that's become so prevalent in mainland exports over the past decade.

There's very little action, lengthy dialogues are often shot very simply from one or two iconic, almost stationary cameras and the townspeople frequently serve as a massed chorus echoing whatever key plot point just took place. Yet the rules behind the formal structure are never forced on the viewer, much less allowed to detract from the narrative.

This is in comparison to most of the recent big-budget wuxia pian movies which deal in mythmaking at best, pandering to the audience at worst. Wheat is very much a human story, its cast vulnerable, flawed and generally imperfect. Lady Li is young and out of her depth. The townspeople spin wild rumours out of the slightest hint of good news. The deserters are resourceful, but can't handle thinking ahead; they bicker and squabble and fail to come down off the fence (help the women, or kill them?) until it's almost too late.

It also manages real levity, beyond the telegraphed gags in much of the competition, and on that note it's often tremendously sensual, both erotic and earthy. High or low art, using the harvest as a stand-in for the cycle of life isn't new, but He Ping's script handles either option beautifully, whether it's the repeated scenes of Lady Li pining for her husband or thigh-slapping giggles as the women manhandle the deserters.

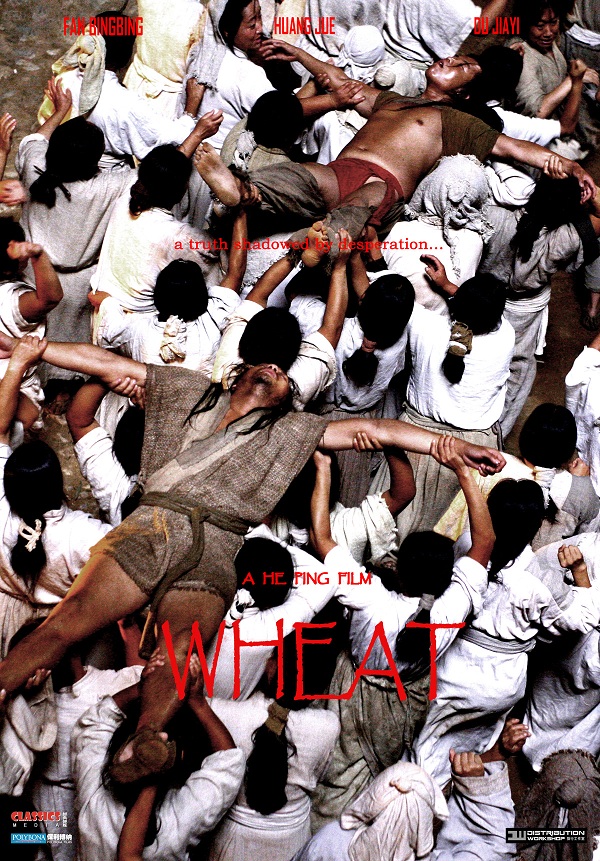

He also knows when to bring the hammer down; when there's finally no hiding the truth the climax is shockingly, horrifyingly effective (despite the lack of any gore). Far darker than the viewer might expect, true to the theatrical motifs throughout it remains fantastically paced, even throwing in at least one sardonic (if predictable) joke and a haunting, achingly sad ending that echoes the original classics of the Fifth Generation.

On just about every level Wheat represents an amazing return to form. Where Warriors suggested He Ping wasn't sure what to do with major studio backing at that time, listless, poorly edited and very much style over substance, in Wheat the director and his crew seem in almost complete control.

Shot in Mongolia, Zhao Xiaoshi's cinematography is frankly jaw-dropping, effortlessly composed, worlds away from tourist guidebooks like Jacob Cheung's Ticket. Where Warriors was badly hurt by shabby set-dressing and TV-quality CG Wheat is intimate, minimal, carefully polished, and where Warriors wasted superstar Bollywood composer A R Rahman, Liu Xing's score gives Wheat an air of matinee melancholy far beyond the laboured miserablism of many of his peers.

The only sticking point is arguably the two deserters - Du Jiayi comes close to painfully grating as the simpleton, but the climax does use him as much more than comic relief and the script never insists the audience sympathise with either man. Wang Zhiwen is gloriously villainous as bandit leader Lord Chong (and almost unrecognisable under old age makeup), but it's Fang Bingbing who steals the film - finally cast in a substantial role after some appalling misfires, the young actress more than holds her own.

A stunning production in every respect, then (bar a few very minor complaints), guided by a master working at what feels like the peak of his game, Wheat stands out amongst recent mainland cinema. Moving, compelling and thought-provoking, it neatly sidesteps both arthouse clichés and government-sanctioned platitudes to bring audiences what has to be one of the best films released this year, and definitely comes hugely recommended.