Edinburgh 2017 Interview: DELICATE BALANCE (FRAGIL EQUILIBRIO) Director Guillermo García López Talks His Socially Conscious Doc

Guillermo García López’s debut feature Delicate Balance delivers an engaging discourse on the inequalities and ailments faced in modern society.

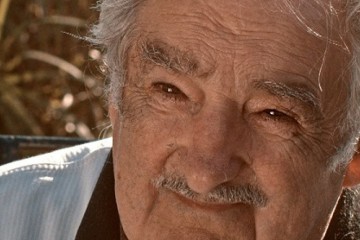

Centered around an interview with Jose Pepe Mujica, the former President of Uruguay who earned global recognition for his words and actions against inequality, the film centres on three different countries, drawing lessons from the people and situations found in each one.

In bustling Tokyo, a salary man questions the futility of his work dominated life; in Spain, families struggle with eviction from their homes as the economy crumbles; and in a settlement in Morrocco, people face death in order to escape into Europe. Despite the dark themes of injustice and emptiness explored, this deeply engaging work ultimately offers a powerful message of optimism for the future.

Sitting down with the director at Edinburgh International Film Festival, I was able to discuss some of the issues explored within his film.

You got your start in filmmaking with a credit on BLANCANIEVES, which is fantastic, but your debut feature here is obviously very different and very personal. Do you consider yourself a documentary filmmaker?

Actually, I don't like to tag myself, so I don't consider myself just a documentary filmmaker. I think that stories have their own timing. Maybe a story has to be a feature, maybe it has to be a short and in the same way stories need a genre.

So with this story we had Mujica’s speech and we thought that having him in the story was a point of view from reality. We couldn't make a fiction with his speech so that's why we chose to approach it as a documentary, but we felt that fiction and nonfiction have a thin line separating the two concepts and sometimes they are intertwined.

For us this is a way of thinking that fiction and nonfiction in life are intermixed, we don't know when it's a fiction and when its reality. What is reality?

Did the project start from Mujica, was his writing and teaching the genesis?

Well, he was in terms of how I got inspired by his speech at the United Nations on the 21st September 2013. After I heard this speech I felt I would like to make a film with these ideas.

He was talking about myself and I felt that hearing a politician talk about human issues seems to be normal, but it’s not normal. And we found that he speaks in a cinematic way, he speaks with images and his own voice is like a melody. We thought that it was the main element to start the project.

It was the starting point but actually I wrote the whole project with the three stories intertwined, the visual treatment and the sound treatment and also the issues that we would like to talk to Mujica about, and then I showed the document to him and after some time he accepted to participate in the project. But yeah, we had the whole project well structured from the start.

After taking the project to Mujica, did he have any say on the countries that you chose and the stories you were planning to tell?

He knew about that. It was amazing because I needed just five minutes before the interview with Mujica alone to talk with him and say we want to do this, this and this. He was looking away at some point on the horizon and then he turned and said, “Ok, I got it lets go”.

And then in the interview he talks about Spain, about Morocco, about Japan. What we were talking about were not new stories, these stories are happening at different times in different places. It’s always the same story. Crisis inside the third world, immigration. What is immigration? Immigration is movement, it’s searching, it’s happiness, it’s sadness. It’s supposed to be happy on one side of the fence, and sad on the other.

There’s always this tension. We can translate this metaphor of the fence to our own life. We are putting up fences every day, with every one. It’s not just this story of African immigration, it's a story of fences between people. And the same with Japan, the story of freedom and duties. We are choosing and it’s difficult to choose. It's a human condition story.

Why did you choose these three cities?

There could have been a lot of different stories. We had a very nice parallel project to make a website with a timeline where everyone could put there own story on this timeline, through a video, a text, a website or a public space installation.

I’m telling you this because there are a lot of stories there. And I think the audience can find themselves in each story. So it’s like a representation of different human issues.

We chose those stories because it's a good way to talk about immigration, escaping from the misery and looking for freedom as a metaphor for life.

For example Japan, I think we in the western world have the same problems as they do in Japan, so it’s not a Japanese issue it's a human issue. Also social housing and problems of housing, having the right to be under a roof, it’s a problem of humanity.

Also, the trip to freedom from Africa, the journey starts in Africa; they’re looking for freedom, looking for life, they have a lot of strength but not material things, so when they are travelling, they escape with a lot of fire and power. This is life. This sense of looking for life and what is at the top, at the end of their trip, well they are looking for the north, the first world, material things. Something to wear, money… they are looking for Tokyo.

But what is the real fact we can find at the end of this journey? Well, at the beginning of the trip they are looking for life, at the end of the trip they are killing themselves. They have material things but not the strength and power of life that Africans have.

At the middle of this trip is this strange place, Spain. It’s supposed to be a democracy, inside the European Union that defends human rights. It’s an example of well-structured countries and democracies but it’s false. We find these human rights violations, that's a very dark point for the history of our country.

Two of the stories contained conflict, Africa and Spain, but one of them, Tokyo, was passive. Was this an attempt to get to the extremes? The polar opposite scenarios?

That's a very interesting question because it’s mathematics. We have the number three. There’s always two and one.

In Africa and Spain we have the conflict and also the resistance. In Africa they resist their fences. And there’s also explicit violence in both. There’s a conflict and a resistance. In Japan we have a conflict but there’s a hidden resistance, it’s very subliminal, very delicate.

And also there’s another group of two and one. Japan and Africa because they are extremes, they are opposites and there’s Spain in the middle of that. In Africa you know that there’s nothing and there’s a lot of strength. In Tokyo you know there’s a lot of things but there’s no strength for life. But you don't know what’s happening in Spain.

This is a confusion of the metaphor for the system; it’s like a kind of hypocrisy. I’m supposed to be in the north but I’m hiding the problems that I have from the south. In Spain that happened. At the same time in Japan they don't want to show the problem of suicide to the world. Do you know suicide due to the excess of work? That's crazy. Why are we working?

The system has to change everything. What is work? That is the question. What is being paid? What is being compensated? I would like to contribute to the world with my work and maybe I could find other ways of surviving. Not just put a value on my work.

Why in my country does my work have this value and I go to the United States and the same work has another value. Who is this God that assigns an amount of money to a concept?

The salary man in Tokyo, mentions suicide in such a casual way, like “this is something I could see myself doing”…

Yes, a psychologist I talked to could see the symptoms of suicide risk in the answers that he made. Actually Masaki-san when I met him, he was coming to the station late because a friend of his had just committed suicide, and I felt I didn't need to push him on that conversation because that reality is inside him and he can talk about that without a guide, but it’s about culture also.

We are passionate about life in some parts of the world and afraid of death. But maybe in some countries there’s not this fear of death and maybe we, you and me, are considering suicide from our point of view that it’s crazy for others there are other things that are important, apart form there own lives.

It’s interesting from our point of view, we see Japanese culture as very individualist, I can see for example in Spain many people saying they are very strange, Japanese culture, but why are they strange? We are judging them and trying to say they are individualist, but I learned Japanese think first on their collectiveness and them on themselves as individuals.

We are trained on our own rights, we are a society that defends our own rights, they anticipate and put duties in front of their own rights. So this is something we should consider when thinking about a new world, a new positive future.

What was the process in finding the individuals within these stories?

It's a very ambitious project in terms of creativity but a very modest one in terms of production. We didn't have public funds or private funds, we used our own with a small part from crowd funding, but very small.

We couldn't go to pre produce and prepare so much, this is not usual and it shouldn't be done in this way but we couldn’t do it another way, so we just went with it. I went with my producer and partner in crime Pedro Gonzalez Kuhn. I went to interview Mujica in Uruguay by myself and then I came to Madrid and shot the interview, and we said let’s not wait anymore, let’s go to Africa.

We can’t wait to have funds to make the perfect trip, let’s go with a camera and try to find it. We went and we were lucky and we found people and shot their stories!

It was difficult to have confidence with them and let them show their faces to the camera, we only had two evenings so it was very hard. It was the same story in Spain, I was looking for stories, we went to the neighborhoods and I knew a lot of families with the same problems related to housing.

And finally I went to some evictions then I found a freelance filmmaker who collaborated with me, and he knew a lot of the eviction issues because he had been working for two years on social issues and so he gave me some images and helped find images to record and also some characters that were in the images.

In Japan I had a production service and they helped to find places and the most important thing to be connected with the story and be honest with the speech and message and they helped me a lot with connecting to the real Japan, so it’s very authentic.

I want to mention Nakanouchi Tetsuya, he understood perfectly the film I wanted to do, he helped me to find the real places, the real characters that showed the issues from the point of view I wanted. He showed me an underground Tokyo.

It was very interesting because we both were following in the steps of Ozu Yasujiro, Chris Marker, Wim Wenders, and we enjoyed going to Ginza, to Golden Gai going to the same places that these people were shooting. It was for us learning about a different Tokyo.

And the sub-Saharan guys?

It was difficult to arrive there because you get lost. It’s in the mountain and then there’s the military. The military go to the camp at night and they beat them, they break their hands, take their food. They hit them and break their bones. So they can’t even approach the fence.

Actually this military, they kill the people, they run over the bodies in cars and they enjoy that. They are racist; I know that, I saw it and I heard stories from the African people and others.

At night they go directly to the camp, not to the fence and they burn the food; the food that the people take from the rubbish. The military, from Morocco at least, they go there and they burn the corn, hit them and kill them. I saw those images.

Some of the images, in Spain of the evictions, how did you get that?

Well, you go to the homes at midnight and you stay there because the police are doing evictions. They close the streets so you can’t go inside at night so you have to stay there and then in the morning you wake up and the police come inside.

This is very hard to find because normally you don't know about the evictions but I had that contact and he had spent two years of his life going there and getting those images. The atmosphere at night is crazy, it’s like a horror movie, do you remember Julio Cortázar’s tale ‘Casa Tomada’ House Taken Over? It’s like that. I don't know who these guys are but they’re taking me from my house with my kids they go to the streets.

The way the images are edited together, there are moments when it’s difficult to tell if it’s Tokyo or Spain or wherever. Was that intentional?

With a Delicate Balance there is one location: the city, the contemporary city. We feel that all the cities that we have been shooting in are the same and we treat them the same.

So it’s like a clash between the different cities that make the main location; the urban landscape. For us it’s important to think about the urban landscape and the relations there. We treat the whole story as a collage of different perspectives from different countries.

We work collectively with different crews around the world, but in the end we feel the same as you. We used different languages, different approaches, different techniques to shoot in cities but in the end we feel that the shooting has been made by just one person and that's like a metaphor for our message.

We speak different languages but we’re talking about the same thing, the human issue.