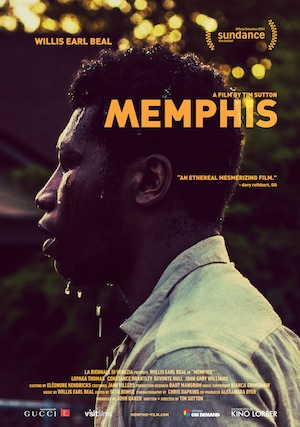

Review: MEMPHIS, A Mesmerizing Meditation On The American South

Tim Sutton's second feature Memphis is that rare and soulful film that causes one to remember why going to the cinema can be one of the greatest joys in life. It is a film that glides somewhere between narrative feature and documentary to striking effect. Its realities are conjured from the everyday, of Memphis, of its people, and filtered through myth and religion, childhood and music, madness, love, and that one mysterious figure who looms over it all: Willis.

Recalling such radical cinematic works and movements as the Czech New Wave to Charles Burnett's seminal docu-drama Killer Of Sheep, and perhaps even a little Hong Sang-soo, Memphis behaves like a collection of field recordings strung together to create little portraits of pocket universes: the street corner that the locals hang out on, the thunder-rolling hallelujahs of a Baptist church, the neon-buzz spectacle at a roller rink, that big empty house with a chandelier all lit up, sitting on the living room floor.

But before get to all of that we begin with Willis. The young musician steps onto the stage of a TV studio to participate in a popular local talk show about music. "I'm not into music. I'm into sorcery," he states. "And the thing about sorcery is how you conjure up the life you want. I consider myself a wizard, and life is an artifice. Everything is an artifice." And so in one graceful, equally bizarre and inspiring lay of words the mood and tone of the film is set.

A collection of artifices then. Worlds to consider. Sutton and his collaborators desire to build worlds, beautifully lived in worlds; fabricated out of necessity and vision and lack of vision and end of vision; places for us to consider and feel invited into. And sure enough there are plenty of moments in Memphis that I just flat out wanted to step right into. Boys on their bikes glide over empty parking lots, cutting through puddles like champions. Willis wandering in the woods, swinging a broom around like a sword, bashing tree trunks. Willis clomping down a broken sidewalk, using the broom as a walking stick, the music -- Willis' music -- languid yet heavy and soulful, starting up in fits on the soundtrack. A white Cadillac prowling the streets at night, street lights smeared like tears on the lens. The back window of that same Cadillac smashed in, shards of glass dropping like icicles as the car grooves along the asphalt.

Willis talks to an old man about The Twilight Zone.

He's seen them all. The old man tells him that he's got to get into the

studio and make an album. "I wish I was a tree," is Willis' reply. "Do

you ever wish to be a tree?" The old man scoffs. "Willis we need a

record." "We need trees," Willis retorts. "We need oxygen." If Willis is

the philosopher then Memphis is his muse. He sits in a cafe and talks

about glory. "You won't find glory in bars. You won't find glory in

pussy. I fucked the dirt one time. I was walking down the street with an

American Apparel ad in my hand and decided to drop my trousers and fuck

the dirt. The dirt is soft and warm." Willis is a journeyman of our

time. And an artist operating outside of time.

Willis talks to an old man about The Twilight Zone.

He's seen them all. The old man tells him that he's got to get into the

studio and make an album. "I wish I was a tree," is Willis' reply. "Do

you ever wish to be a tree?" The old man scoffs. "Willis we need a

record." "We need trees," Willis retorts. "We need oxygen." If Willis is

the philosopher then Memphis is his muse. He sits in a cafe and talks

about glory. "You won't find glory in bars. You won't find glory in

pussy. I fucked the dirt one time. I was walking down the street with an

American Apparel ad in my hand and decided to drop my trousers and fuck

the dirt. The dirt is soft and warm." Willis is a journeyman of our

time. And an artist operating outside of time. When we finally do hear Willis sing it is during a studio session. Veteran musicians, crooked toothed and sharp eyed, line the corners of cheap wood paneled rooms. Willis sits at the piano, bathed in a deep ocean blue light. He is wearing sunglasses. He's talking about how the music has changed. Changed from when it was on the page to now being off the page, being played. The veterans don't quite get it, but they play along. Willis' voice lays smoothly over the soundtrack, organ and drums coming up, and then... his voice cuts out, we are left with the organ and a close up of Willis singing, but we can't hear him. This type of play with picture and sound is used extraordinarily well throughout the film's 79 minutes, emphasizing Willis' increasing isolation and willingness to abandon himself and all others, and just wander. And so he does. Right into the woods. "Now I can just look at the trees and the sky and be happy," he says.

A tenderly spiritual film about other worldly artists occupying spaces in this world, Sutton's self-described liquid narrative will certainly not be a film for audiences who are looking for a traditional story with easy to digest conflict, catharsis and closure. But as a truly experiential work Memphis is a singularly unique and dynamic vision with a mesmerizing subject in Willis. The city is lovingly shot by Chris Dapkins, with each street, each person, glowing softly with a near mythic quality that can only be found in the everyday. Backed up by the truly transgressive, avant-garde and yet soulful musical stylings of our lead subject, Memphis plays to the beat of its own drum, and it is, indeed, glorious to behold.

This review was originally published in slightly different form during the Sundance Film Festival in January 2014. Memphis opens in NYC on September 5 at IFC Center (with a sneak tomorrow night), and in LA at the Sundance Sunset 5 on September 12.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.