SEPTIEN Director Michael Tully On Crafting His Southern Gothic Vision

Michael Tully has been a regular fixture in the independent film scene since the beginning of the last decade, supporting David Gordon Green in the making of George Washington. In that time, he's directed three features of his own, including the utterly strange Septien, which he co-wrote, directed, and stars in. Tully plays Cornelius, a star athlete who disappears from the family home for 18 years only to return to his wildly eccentric brothers just as mysteriously as he left.

Here's the official synopsis:

Eighteen years after disappearing without a trace, Cornelius Rawlings returns to his family's farm. While his parents are long deceased, Cornelius's brothers continue to live in isolation on this forgotten piece of land. Ezra is a freak for two things: cleanliness and Jesus. Amos is a self-taught artist who fetishizes sports and Satan. Although back home, Cornelius is still distant. In between challenging strangers to one-on-one games, he huffs and drinks the days away. The family's high-school sports demons show up one day in the guise of a plumber and a pretty girl. Only a mysterious drifter can redeem their souls on 4th and goal.

With today's release of the film at the IFC in New York and nationwide on VOD, we thought we'd speak with Tully about his film.

ScreenAnarchy: Some reviewers have called your film a type of "Southern Gothic." How much do you agree with that view of Septien?

Michael Tully: I confess to being quite pleased--and honored--whenever that reference is made, for not only am I a fan of the Southern Gothic tradition, but it did in fact play a very conscious role in the film's thematic, tonal, and narrative conception. Granted, the whole experiment of Septien was to toss many different influences into a pot and see if it stirred up into an even somewhat coherent soup, but Southern Gothic was without a doubt a primary source of inspiration. While I am more than okay with low-budget American films that are more representational of the modern world in which we live, I thought it would be a more daring--and fun--challenge to try to make a Southern Gothic comedy that explored male repression with the sincerity of a naturalistic, humane drama.

ScreenAnarchy: What was the journey to get your film from the page to the screen? How long was the span from the initial idea to the final film?

MT: In early 2010, Onur Tukel sent me a link to a short film he had just made called The Wallet (I highly recommend watching it here). When I saw Onur onscreen, I was immediately reminded of an idea I'd had almost ten years prior, in which we played brothers on a farm. That was as far as the idea had ever gotten. But watching The Wallet got me thinking about it again, and after a 90-minute brainstorm session over Irish Coffees at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival with my friend David Gordon Green, the core skeleton of Septien had taken shape. For whatever reason--I have at least five other movies that I've been wanting to make for many years now--this particular idea, which seemed more like a preposterous inside joke than anything else, sparked something inside me that said it had to be done, and quickly at that, before we could psych ourselves out. After that conversation, the wheels were set in irretractable motion.

In February/March, Onur, Robert Longstreet and I exchanged emails developing our characters and further fleshing out the story. Initially, I didn't even want there to be a script. I just wanted to shoot a cobbled together list of moments and scenes that I thought would be cool to watch. But thanks to the influence and participation of Onur and Robert, a narrative began to take shape to the point where I opened Final Draft, typed "FADE IN," and then typed a whole lot more.

In April, while at the Sarasota Film Festival, I befriended Nomadic Independence Productions' Brooke Bernard and Ryan Zacarias, the team behind Brent Stewart's The Colonel's Bride. A month or so later, when I still didn't have a definite production agenda--I'd been planning to shoot in Maryland, where I'm from--I spoke to Brooke and Ryan, who dug the script and sold me on the idea of shooting in Nashville. On June 29th, my DP Jeremy Saulnier and I drove from Brooklyn to Tennessee. From July 5th-20th, we shot the film. After syncing the sound myself (with the help of Christopher Gebert), I gave the footage to our thorough-but-quick editor Marc Vives, who put together a great 105-minute assembly from early August to September 15th. The next two months were spent refining that into the picture-locked version, at which point the sound work--thanks to composer Michael Montes and sound re-recording mixer Gene Park--and color correction--thanks to Alex Bickel at Company 3--happened.

It's rather staggering to consider that we will be opening theatrically at the IFC Center on July 6th, 2011, exactly one year-plus-one day from when we started shooting. Believe me, I am well aware that this project has had a miraculously quick turnaround and I'm sort of scared to make another film for that very reason.

ScreenAnarchy: The roles of your brothers in the film required a certain amount of fearlessness. How did Robert, Onur, and yourself decide to take on the leads?

MT: The initial primary idea for the film was that it would star Onur and myself, so that is how it was always designed. Robert was initially going to play the role of the Red Rooster, but he got jealous and wanted to be a brother, too; hence, Ezra. The entire project was filled with a reckless, anything goes type of spirit, so while Onur and I expressed worry about our non-actor selves taking on such prominent roles, and while Robert expressed concern diving headfirst into such a strange character, this was simply how it had to be. Holding a casting call for the parts of Cornelius or Amos or Ezra Rawlings would have been a hilariously silly thing to do.

ScreenAnarchy: What was your experience with the South before making the movie? Did you grow up there?

MT: I grew up in Central Maryland--Mt. Airy, to be exact--which is a very small town. I passed farms on the way to school, and my high school was pretty much surrounded by cornfields. Maryland is right on the line between the North and the South, but where I'm from has much more in common with the South. I've also spent a lot of time in the South, having lived in Athens, Georgia, for a short period and having visited my good buddies at Winston-Salem's North Carolina School of the Arts in the late '90s. Whenever I'm at a dinner party in New York and people make jokes about the South, I take it personally. If pressed, I would label myself a Southerner more than a Northerner, though the truth is that I'm a Delmarva-er!

ScreenAnarchy: What kind of prep did you perform with your co-stars for their roles?

MT: We did more talking about our characters than actual rehearsing. As actors were arriving throughout the shoot and I was consumed with directing the film during the day, at night most of the time was spent preparing for the following day by talking scheduling with our AD Drew Bourdet and discussing a visual plan of attack with Jeremy. Thus, it was virtually impossible to do any serious rehearsing. A pattern that emerged was that we would do our best to gather a few hours before an impending scene to talk things over and do a loose walk-through with the actors, at which point they could hopefully get a better handle on things and feel as comfortable as possible once the camera began to roll.

ScreenAnarchy: Some of the moments seemed like real meltdowns for both the characters and the performers (I'm thinking of Ezra's rant at Amos about the puzzle piece and the whole sequence in front of the fire). How much of what was on-screen was in the script and how much just came out while the cameras were rolling?

MT: When you're shooting a movie on celluloid and only have 16 days in a row to do it, you can't afford to shoot aimlessly and hope things turn out okay. We had a very concrete plan, as well as a script. But part of the fun of making movies is to align yourself with people who are smarter than you will ever be, so I tried to get everyone off the page as much as possible and let them bring their own sharp minds to the table. Having said that, the film actually reflects the screenplay way more than one might think, though that puzzle eruption by Ezra is a good example of Robert taking things just one step further with his intense performance and his injection of "I could spit hornets!" into that particular take. As for the bonfire sequence, that was a situation where we had a plan for each character's personal exorcism, dialogue included, but we also decided to not do traditional coverage and instead let things be as one-take spontaneous as possible. As you can imagine, that night was really, really weird.

ScreenAnarchy: Where did Cornelius come from?

None of the character's pain came from personal experience, if that's what you're asking, creep! Seriously, I don't know where he came from exactly. I think my initial idea was to take the Vincent Gallo anti-hero to a comical extreme. The depths of Cornelius's lingering pain emerged gradually, as we got further into the production itself. I wrote sports into the script that I played growing up, feeling somewhat confident that my basic skills and Marc Vives's magical fingers would result in the character seeming to be a truly gifted athlete (which I am not in real life). Because the character is so muted and simply is, I thought I had an innate link to him that would hopefully result in a somewhat convincing portrayal. This also removed the added energy of having to direct another actor. My direction to myself while shooting was "narcoleptic Jesus." Whenever I had to be extra sad, or especially in the scene when I needed to cry, I just thought about the debt I was putting myself in and how all of these great people were busting their asses for free and I had better make myself look genuinely somber or I'd be crying some dangerously real tears a couple months down the road.

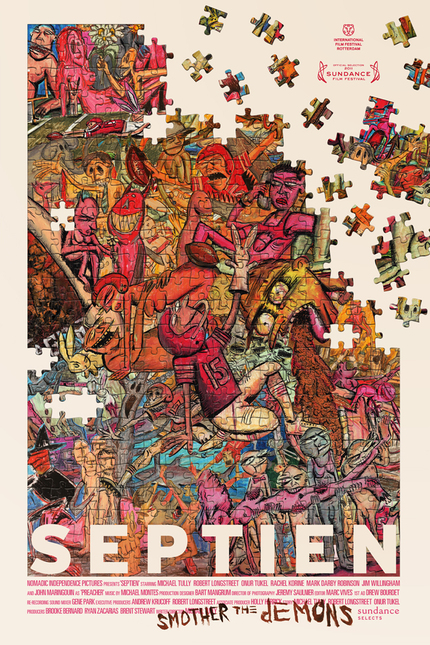

ScreenAnarchy: Who was responsible for the terrific illustrations and paintings the character Amos created in the film?

MT: Onur Tukel is not only a supremely gifted writer/director--and I now believe he's proven himself in front of the camera as well--but he's also a hyper-talented visual artist. He himself made all of that demented, twisted, deranged--yet somehow still humorous and sweet--artwork, which takes the movie to a whole 'nother level. As he also did much of his own character development, I'm confident that this enabled him to tap into his subconscious in a way that an artist-for-hire never could have. It brought my adjectives-in-the-script to life in a way that continues to amaze me.

ScreenAnarchy: What are you working on next?

While Hollywood hasn't come a knockin' after Septien, I have managed to align myself with some fine folks who are committed to finding actual money to help me finally realize my 18-years-in-the-wishful-making dream project called Ping-Pong Summer. The easiest way to pitch it is The Karate Kid (Daniel LaRusso version, thank you very much) meets Wild Style but instead of karate we're talking about... yes, that's right... ping pong. I desperately want to make PPS feel like a lost gem from the mid-1980s as opposed to a 2012 movie looking back on that era with cloying irony. Think This is England versus The Wedding Singer. But with stupid fresh beats.

Septien opens today at the New York IFC and is available nationwide on VOD.

(1)-thumb-80x80-93563.jpg)