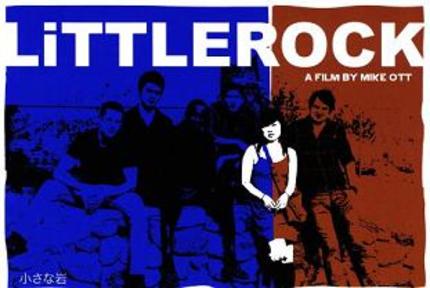

BIFF 2011: LITTLEROCK review

Littlerock is different. Mike Ott's sophomore film tells the story of two Japanese teenagers, brother and sister Rintaro (Rintaro Sawamoto) and Atsuko (Atsuko Okatsuka). They've stopped off in the small town of the same name on their way to make a pilgrimage (though where they're going isn't explicitly revealed until the epilogue). Passing the night in a tiny motel room, kept awake by the party audible through the wall, when Rintaro asks the revellers to turn it down the siblings find themselves unexpectedly invited to join in.

Most of the other guests are fairly indifferent to the new arrivals, but Cory (Cory Zacharia) latches onto them the moment they walk through the door. It slowly becomes apparent Cory's not quite the life and soul of the party he'd like Rintaro and Atsuko to think. In reality he's an angst-ridden, ineffectual loner deep in debt over petty drug deals with the local jocks, unwilling to acknowledge his own failings and convinced an outsider like Atsuko will understand how different he is.

Even when Jordan (Brett L. Tinnes), another of the party-goers, finally makes a move on Atsuko and she's obviously far more interested, Cory refuses to give up hope. Overawed by this strange little love triangle, Atsuko persuades her brother to let her stay in Littlerock while he carries on travelling by himself for a time - even though she doesn't speak a word of English.

Very little happens in Littlerock. There's no pivotal dramatic moment once Rintaro leaves, and most of the plot threads aren't even wound up by the time the story's over. Even at a lean eighty minutes and change there's no real sense of urgency to the film, with Ott and DP Carl McLaughlin patiently working in some gorgeous rough and ready footage of the surrounding desert and the setting sun, or shooting a midnight party as some hazy, idealised dream of adolescence.

At the same time it's not the languid, affable paean to slacking off it might appear. Okatsuka gets a writing credit along with Ott and McLaughlin, but from the moment Cory's erstwhile friends first mercilessly put him down it's obvious one or all of the three have a keen ear for the casual cruelties and constant jostling for status young people have to go through. The dialogue dips into platitudes once or twice, with racist abuse that comes off like something out of an after-school special, but for the most part it's phenomenally eloquent stuff, for all its themes are essentially mundane or its cast tongue-tied.

Few slice-of-life films show such keen empathy for their characters. All the principals are unbelievably well drawn - none of them exceptional, but fully, plausibly human and multi-faceted, capable of little moments of grace as much as pettiness and spite. Cory is pathetic, true, but he's not vindictive or hurtful and genuinely cares about Atsuko, much as he doesn't want to admit she's not interested. Jordan's kind and considerate, but thoughtless and hardly mister right.

And the idea Atsuko can't speak directly to any of them is far from the blunt instrument it could have been. Ott and his cast handle this aspect of the narrative, the gulf between Atsuko and each of the boys, with wry, self-effacing wit but achingly savage pathos, too, when events call for it. Cory raises a laugh when, challenged by Jordan ('Do you actually understand what she's saying?') he has to admit he's bluffing but later, when he has to face up to the reality he can't get through to her the way he'd like his pain is heartbreaking for all the character's contemptible.

Littlerock acknowledges these things pass, that young people grow up, change and move on - but it understands unrequited love, rejection and adolescent friendships are still important, still part of the bigger picture. When Rintaro can't understand why Atsuko's so taken with the place ('These people just sit around and get high every day. You call them friends?'), we see his point, but also his sister's hurt and confusion. When the two of them finish their pilgrimage, it's a solemn moment, but one where Atsuko realises her stay in small-town America has become just as much a part of who she is as their original reason for coming.

It's not perfect, perfect. Ott makes a couple of questionable decisions, in particular one plot point in the final act that feels suspiciously like an excuse to wrap the story up a little more conveniently - though even that's made up for by a beautiful last-minute resolution. Nonetheless Littlerock is amazing stuff overall, a tender yet unflinchingly honest, thought-provoking little story of identity and self-discovery. Raw and punkish but still tremendously accomplished, Mike Ott's second film is easily one of the best slice-of-life romances in years and comes unhesitatingly recommended.

(Littlerock was screened as part of the 17th Bradford International Film Festival, which ran at the UK National Media Museum from 16th-27th March 2011.)

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.

(1)-thumb-80x80-93563.jpg)