Review: James Franco's CHILD OF GOD Is A Revelation

My own relationship with the man was born of indifference and suckled at the teat of hatred, thanks in no small part to the 2011 Oscars. But his skeezetastic turn in Harmony Korine's Spring Breakers weaned me of my hate, and I'm slowly starting to feel the love, if not for his artistic output, then at least for the audacity of his career choices. He's pretentious yet self-deprecating, prudent yet reckless. He stars in blockbuster tentpoles, ridiculous self-referential soap opera arcs, makes no budget art films, and adapts "unfilmable" works of literature. I don't know, but I think it might be time to start taking him seriously.

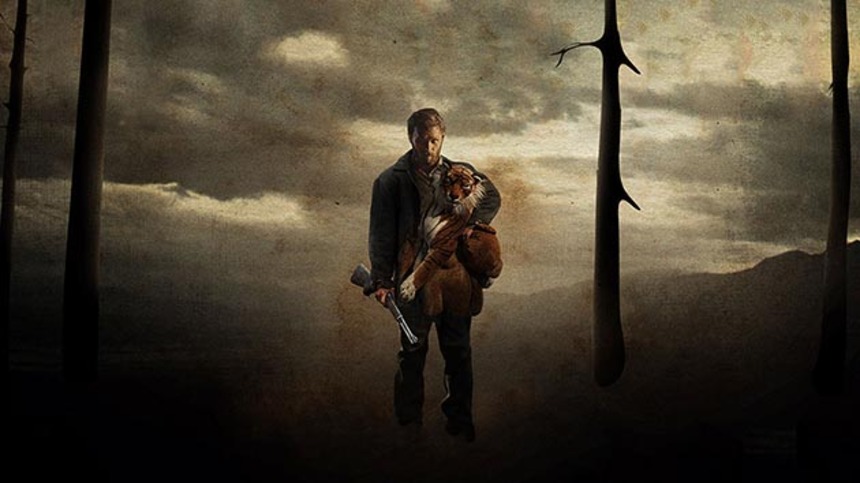

So what does Franco have for us this time? Why, it's an adaptation of Child of God, Cormac McCarthy's chilling Southern Gothic about a "dispossessed, violent man" named Lester Ballard whose life is "a disastrous attempt to live outside the social order." He is, in the author's own words, "a child of God much like yourself perhaps."

Now some of you might take exception to that statement, what with all the murderin' and corpse fuckin', but I think both McCarthy and Franco have a point. Child of God is a portrait of the humanity that resides in even the darkest of souls. Even someone like Lester Ballard, who is more beast than man. Despite what a certain church claims about God's affinity for gay people, I seem to remember a Sunday School song about Jesus loving ALL his children. Red and yellow, black and white, even the necrophiliacs are precious in his sight.

So like it or not, Lester Ballard is one of us. Scott Haze fully commits to the role and let me tell you, it ain't pretty. Speaking in garbles flecked with spittle most of the time, he still manages to project a wide range of emotions in a surprisingly nuanced performance. Credit is due both to Haze and Franco for making a date between a sociopath and a corpse one of the sweetest scenes you'll ever see (right before it gets really ugly, that is). I don't know where this guy Haze came from, but Franco knows he's got a good thing going. He's cast the actor in his last four features. Seriously, Haze's performance here is a fucking powerhouse. If it weren't for the squeamishness of the Academy, I'd say he was a shoo-in for a Best Actor nom. He carries the film like it weighs nothing.

I know, I know. Actors of that caliber direct themselves. You want to know if Franco's any good behind the camera. Like you, I had my doubts. The film begins with the auction of the Ballard family home and its surrounding property. Lester shows up with his trusty rifle to put a stop to the proceedings, threatening people's lives and hollering like a lunatic. It's a jarring beginning, full of shaky, out of focus handheld camera work. Theoretically it works for the scene, acting as an extension of Lester's mania, but it's hell on the eyes and is easily construed as amateurish. Thankfully the cinematography settles down, transitioning to a less seizure inducing style, even as Lester becomes more unhinged. Towards the end we are even treated to some scenic vistas and honest to goodness shots on sticks. It's as if the all-seeing eye of the audience becomes more sympathetic to Lester the more inhuman he becomes.

Franco makes a number of other creative choices that work better for the film. McCarthy is known for his prose, even in his more sparsely written novels. Franco chooses to physically put McCarthy's words on screen to help set the tone of the film, introduce us to its vocabulary. We're not talking huge passages here, just the odd sentence or two. He also utilizes voiceover to fill in Lester's backstory. Unseen characters relay anecdotes of who Lester was to help us better understand the man he has become. It is a refreshing alternative to flashbacks. It also gives the film a sense of the literary that is so often missing in these types of adaptations.

But none of these flourishes come off as superfluous or self-conscious. Franco's direction is natural, assured. In fact, if he hadn't cast himself in the most inconsequential of roles--which frankly was a bit of a distraction--Franco would be completely invisible in this film. For a man who wears so many different hats, many of them silly, this is a good thing. It is McCarthy's creation that drives the film, his world the story exists in.

You know what? I'm starting to think maybe Franco has the chops to pull off those Faulkner adaptations. Maybe he is the right director for Zeroville, one of my favorite novels, which he owns the rights to. His directorial output up until now has been viewed as sort of joke, but after seeing Child of God, Hallelujah! I've seen the light! So consider me one of the converted, ready to spread the Gospel of Franco to unbelievers everywhere.

So what does Franco have for us this time? Why, it's an adaptation of Child of God, Cormac McCarthy's chilling Southern Gothic about a "dispossessed, violent man" named Lester Ballard whose life is "a disastrous attempt to live outside the social order." He is, in the author's own words, "a child of God much like yourself perhaps."

Now some of you might take exception to that statement, what with all the murderin' and corpse fuckin', but I think both McCarthy and Franco have a point. Child of God is a portrait of the humanity that resides in even the darkest of souls. Even someone like Lester Ballard, who is more beast than man. Despite what a certain church claims about God's affinity for gay people, I seem to remember a Sunday School song about Jesus loving ALL his children. Red and yellow, black and white, even the necrophiliacs are precious in his sight.

So like it or not, Lester Ballard is one of us. Scott Haze fully commits to the role and let me tell you, it ain't pretty. Speaking in garbles flecked with spittle most of the time, he still manages to project a wide range of emotions in a surprisingly nuanced performance. Credit is due both to Haze and Franco for making a date between a sociopath and a corpse one of the sweetest scenes you'll ever see (right before it gets really ugly, that is). I don't know where this guy Haze came from, but Franco knows he's got a good thing going. He's cast the actor in his last four features. Seriously, Haze's performance here is a fucking powerhouse. If it weren't for the squeamishness of the Academy, I'd say he was a shoo-in for a Best Actor nom. He carries the film like it weighs nothing.

I know, I know. Actors of that caliber direct themselves. You want to know if Franco's any good behind the camera. Like you, I had my doubts. The film begins with the auction of the Ballard family home and its surrounding property. Lester shows up with his trusty rifle to put a stop to the proceedings, threatening people's lives and hollering like a lunatic. It's a jarring beginning, full of shaky, out of focus handheld camera work. Theoretically it works for the scene, acting as an extension of Lester's mania, but it's hell on the eyes and is easily construed as amateurish. Thankfully the cinematography settles down, transitioning to a less seizure inducing style, even as Lester becomes more unhinged. Towards the end we are even treated to some scenic vistas and honest to goodness shots on sticks. It's as if the all-seeing eye of the audience becomes more sympathetic to Lester the more inhuman he becomes.

Franco makes a number of other creative choices that work better for the film. McCarthy is known for his prose, even in his more sparsely written novels. Franco chooses to physically put McCarthy's words on screen to help set the tone of the film, introduce us to its vocabulary. We're not talking huge passages here, just the odd sentence or two. He also utilizes voiceover to fill in Lester's backstory. Unseen characters relay anecdotes of who Lester was to help us better understand the man he has become. It is a refreshing alternative to flashbacks. It also gives the film a sense of the literary that is so often missing in these types of adaptations.

But none of these flourishes come off as superfluous or self-conscious. Franco's direction is natural, assured. In fact, if he hadn't cast himself in the most inconsequential of roles--which frankly was a bit of a distraction--Franco would be completely invisible in this film. For a man who wears so many different hats, many of them silly, this is a good thing. It is McCarthy's creation that drives the film, his world the story exists in.

You know what? I'm starting to think maybe Franco has the chops to pull off those Faulkner adaptations. Maybe he is the right director for Zeroville, one of my favorite novels, which he owns the rights to. His directorial output up until now has been viewed as sort of joke, but after seeing Child of God, Hallelujah! I've seen the light! So consider me one of the converted, ready to spread the Gospel of Franco to unbelievers everywhere.

This review was published in a slightly different form during the 2013 New York Film Festival.

Child of God opens in theaters Friday, August 1.

Joshua Chaplinsky is the Managing Editor for LitReactor.com. He has also written for ChuckPalahniuk.net and might still be a guitarist in the band SpeedSpeedSpeed.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.