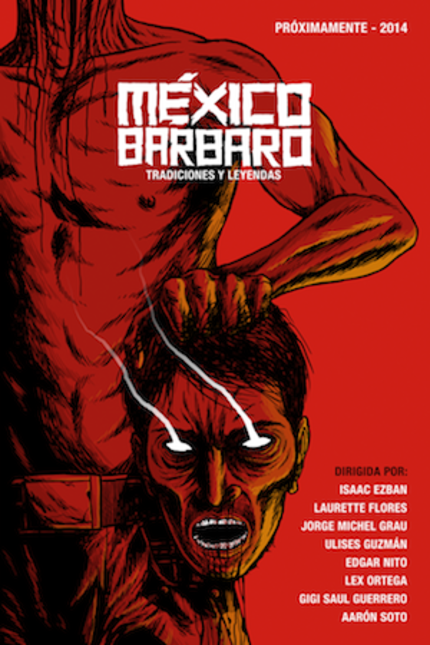

Masacre En Xoco 2014 Review: MÉXICO BÁRBARO, A Horror Anthology That Could Have Been More Brutal

Mexico is barbaric, both historically and due to the violent present.

Rather than making a clear reference to its main concept of exploring Mexican legends and traditions, horror anthology México Bárbaro kicks off as a straight exhibition of the violent side of Mexico, uniting what the old Aztecs did to the present day narco violence.

Look, I'm not saying the opening segment, Laurette Flores' Tzompantli, doesn't work at all as a short story, but it really feels as it was just meant to set the mood of the film. We are living under terror, with narcos sacrificing even the relatives of rival gang members just as the Aztecs did.

While México Bárbaro contains another segment that deals with the narcos, that's obviously not the main theme, though the second short, Edgar Nito's Jaral de Berrios, doesn't fully explain anything about the legend it is based on. This segment in particular is entirely a visual thing, with a simple concept of two Mexican runaways charros arriving to a house that's haunted by the spirit of a woman. Bad things will happen, leaving again an image that now is normal to see in the newspapers: that of a hanging man. With a Western feel, this is the best technical achievement in the entire film.

Then comes a segment like the one by ScreenAnarchy's very own alumni Aaron Soto, which is sort of the opposite of Nito's film in technical terms, as it is the most homemade looking effort. It also has nothing to do with the Mexican present, legends or traditions (and if it does, it doesn't have enough narrative to expose it), and it's underdeveloped in every way. It has a joke involving menstrual blood that worked with the audience, though.

Soto's Drena confirms at the same time that México Bárbaro offers all kinds of styles and stories. The fourth one, La Cosa Más Preciada by Isaac Ezban, is a straight homage/parody of the American horror movies from the eighties: a virgin couple decides to take a vacation by themselves by going to a cabin in the woods, of course.

With a visual style a la Grindhouse (trying to recreate a cheap look), Ezban combines the Mexican legend of the Alushes (creatures from the woods that are not usually evil) with the classic vacation gone wrong thing. It even has the character that warns the eventual victims, but its self-awareness -- the woodsy place is called, for example, the mouth of the wolf --makes it really funny. Plus, there's some nasty stuff, as though it was taken out of a Troma flick, and in general is damn cool for a midnight audience. (For my money, it's the best thing in México Bárbaro).

After being in Valle de Bravo, a woodsy place in the State of Mexico that actually feels like any woods in any American flick, we return to a more Mexican setting (Tlatelolco in Mexico City) with Lex Ortega's segment Lo Que Importa Es Lo De Adentro, though the leader of the project is using a legend not exclusive of Mexico: that of the bogeyman. What Ortega does is to adapt the legend to several real issues: homelessness, child abduction, and organ trafficking. It's simple yet effective, less bloody than other work by the director but more focused in story. It certainly works as an allegory for parents who don't pay enough attention to their apparently exaggerated and whiner kids -- but wait to see who ends up crying and without a single clue.

México Bárbaro decreases in intensity with the next segment: Jorge Michel Grau's Muñecas. Grau uses the great island of dolls setting, but he doesn't go further than just showing images that, like Ortega's segment, indicate that something of real horror is going on behind the curtains. It has gorgeous black-and-white cinematography, and some beautifully creepy images, but it never fully develops as a short with something to say.

The penultimate segment, Ulises Guzman's 7 Veces 7, is the one that touches again on the narco violence. But this one tries to be a real piece of fantastic cinema, elevating a revenge tale to a series of crazy images with an unconventional narrative. Some images are strong, but I was not particularly fond of how the special effects gave it a cheesy feel.

The final segment, Día de los Muertos by Gigi Saul Guerrero, is a strange case. It was made before the conception of the project and, in consequence, it relates to the main concept only shyly as it happens during the Day of the Dead festivity, a Mexican tradition, certainly. However, in itself it's a pretty solid and satisfying short film. Guerrero delivers a more straightforward revenge story set in a brothel, with girly power attitude and the most visceral violence you'll get in México Bárbaro.

Ultimately, and as you can already tell, the film fails to be a cohesive conceptual anthology. When it world premiered at Sitges 2014, it was screened back-to-back with two other recent horror anthologies: V/H/S: Viral and ABCs of Death 2. If I'm going to compare it with those productions, well, México Bárbaro at least doesn't try to unite its eight segments in a way that hardly makes any sense as V/H/S: Viral did, but it definitely lacks the concrete ideas -- as well as the brutality and energy -- that the best shorts from ABCs of Death 2 have. It's a welcomed effort that could have been much more powerful.