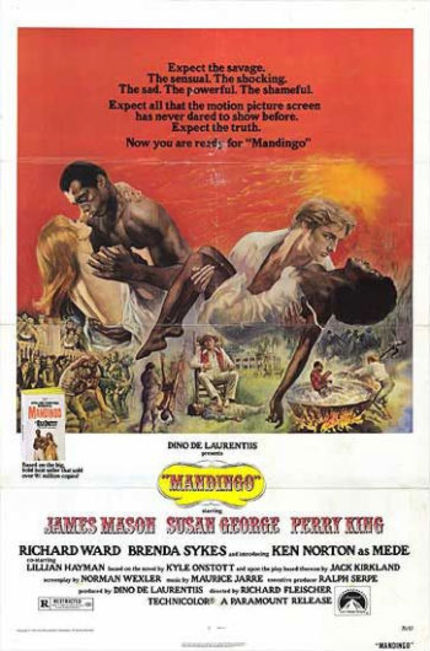

70s Rewind: MANDINGO

If you want to see a movie about race relations in the Deep South, adapted from a best-selling novel, you might be tempted to head out to a theater this weekend and see The Help, a well-meaning and well-performed comedy / drama that should play very well for mainstream audiences.

Or, you could lock the doors, draw the curtains, and slide 1975's Mandingo into your DVD player.

Improbably starring James Mason -- who reportedly needed the money for his alimony payments -- as a sickly plantation owner, Perry King as his son with a taste for comely slave "wenches," Susan George as his sex-mad wife, and boxer Ken Norton as the highly-prized breeder slave Mede, Mandingo is "racist trash," according to Roger Ebert in his original review, "obscene in its manipulation of human beings and feelings, and excruciating to sit through in an audience made up largely of children, as I did last Saturday afternoon. ... This is a film I felt soiled by, and if I'd been one of the kids in the audience, I'm sure I would have been terrified and grief stricken."

Admittedly, the film is highly offensive and scabrous. Yet it's also a riveting exploitation flick, shocking on that score only when you realize that it issued forth from Paramount Pictures. It's not surprising that Quentin Tarantino is a big fan of the movie; he'll next be making his own "slavery Western," Django Unchained, supposedly revolving around the revenge of a slave who was forced to fight in death matches for an evil plantation owner.

Tarantino's premise definitely sounds as though Mandingo was one of his inspirations. The aristocratic James Mason plays Warren Maxwell, the evil owner of Falconhurst plantation, which has seen better times. The grounds are run down and overgrown. Most of the rooms in the main house are bereft of furniture and decorations.

Muddy Waters croons the opening song, "Born in This Time," as "bucks" and "wenches" (children are "suckers") are led in for inspection by slave trader Mr. Brownlee (Paul Benedict) under Maxwell's watchful eye. Brownlee is thorough; he takes the trouble, for example, to peer between one male slave's buttocks! We're further introduced to the 19th Century plantation style of life when a doctor visits and advises Maxwell that his son Hammond (Perry King) must deflower young slave girl Lucy since she's in heat; it's good for her. Ham sighs in resignation; he knows it's his duty, one he's performed many times.

Ham, as he's known, is a compassionate "Massa," perhaps because he has the disability of a bad leg; he doesn't beat his wenches, as his cousin Charles does, and he even takes a special liking to Ellen (Brenda Sykes), a beautiful wench he meets on a fateful trip to New Orleans. His father has ordered him to take a look at his cousin Blanche (Susan George) as a candidate for marriage. Ham is immediately taken with her and proposes marriage. Little does he know that she's not "pure," a condition he discovers to his dismay on their wedding night. That pushes him into the welcoming arms of Ellen, to the steadily-increasing resentment, jealousy, and anger of Blanche.

The tawdry nature of the film's plot, driven as it is by adultery, incest, miscegenation, sexual blackmail, and venal racism, bathes everything with a scummy gloss. Underneath the oily surface, however, issues of substance simmer, voiced by Cicero (Ji-Tu Cumbuka), a rebellious slave who knows how to read, and the gravel-throated Agamemnon (Richard Ward), an older slave who smiles at "Massa" but seethes in private. Their protests are strongly-worded as brief outbursts of 1970s manifestos and are a stirring reminder of the film's heritage. They also serve to raise the consciousness of Mede, who is a Mandingo (or Mandinka, from West Africa) and highly sought-after for breeding purposes. Mede's ability to defend himself opens up new possibilities of exploitation for Ham and his father.

The substance is eventually boiled away by the exploitation elements; as sincere as Ellen sounds when she begs Ham for kindly consideration toward her unborn child, they're both completely naked in bed during their discussion. On the other hand, the full frontal male and female nudity is integrated into the story; the characters are casual about disrobing, except for one key sequence where the nudity takes on a greater meaning.

Susan George, bobbing and weaving around her bedroom like a drunken cat in heat, makes a memorable impression, and so does Perry King as the white man whose breeding eventually shows. Mason adopts a broad "Suh-thuuuun" accent, and adds weird gravitas in a top-billed (supporting) role. Richard Ward lends his own brand of weary gravitas to his small part, while Brenda Sykes is very effective as Ham's true love. Ken Norton is, well, an athlete turned actor. He and Sykes appeared as different characters in Drum a year later.

Richard Fleischer, son of Max Fleischer, began directing in the 1940s, making his mark in the 50s with The Narrow Margin, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and Compulsion. His eclectic career continued in the 60s with Fantastic Voyage, Doctor Doolittle, and The Boston Strangler. He remained an in-demand director throughout the 70s, completing 13 pictures; his most recent pictures before he tackled Mandingo included The New Centurions, Soylent Green, The Don is Dead, and Mr. Mayestyk.

Fleischer's films fell far short of high art, but they were almost always propulsive entertaining, and Mandingo is no exception. You can certainly take issue with the film's relentlessly salacious approach to the material, but it's an equal opportunity offender, slamming slave owners, complicit family members, and poor white trash alike.

The screenplay by Norman Wexler draws from Kyle Onstott's best-selling novel, published in 1957, as well as a play by Jack Kirkland. The novel, running 659 pages, provided a considerable amount of "character and sociological insight," according to one writer known simply as Bunche, who feels that the movie "tarnished the considerable merit and bravery found in the novel." The book appears to be currently out of print.

Wexler had already received Academy Award nominations for Serpico and Joe; his screen credits were few, limited to the Mandingo follow-up Drum, followed by Saturday Night Fever and later Staying Alive and Raw Deal. Wexler apparently suffered from bouts of mental illness, leading to a prison sentence after he allegedly made threats against President Richard Nixon in 1972.

The film was released on July 26, 1975. Jaws, which came out the month before, still ruled the box office (as it would until the end of September), but Mandingo evidently acquitted itself well, at least good enough to justify Drum the following year, based on another novel by Kyle Onstott and adapted again by Norman Wexler.

The blaxploitation craze may have been on a downhill slide, but the studios were desperate enough to try just about anything. Mandingo could only have been made in that era, and it benefits from the higher budget afforded a studio film (and the clout of producer Dino De Laurentiis). For all the sensational subject matter, the on-screen craftsmanship is clearly evident.

It may be sleazy, yet there's no denying that Mandingo holds up as a seriously captivating, provocative exploitation picture.